Associated links (A98H0003)

Wreckage recovery

General

Immediately after the accident, many government departments, agencies, companies, and concerned citizens assisted in the search and recovery of victims and aircraft components. Civilian vessels from the local communities that were positioned offshore near the accident site also responded in great numbers. The close proximity of the LKP (as derived by radar) of the aircraft to Halifax meant that resources were available locally to permit an intense, multi-level government response. Canadian Forces ships were already at sea nearby; and Canadian Forces aircraft, medical teams, and army units quickly responded. Members of the RCMP, CCG personnel, a team from the BIO, and a team from the CHS were quickly on the scene. Because of its SAR responsibilities, major disaster response role, and the size and nature of its assets, the DND was the most appropriate agency for command and control of the initial marine operation. The MOC in Halifax became the shore-based centre for command, and on-scene command responsibilities were assigned to the captain of the HMCS Preserver, the largest and most suitable ship at the accident site.

Initially, the vessels proceeded toward the aircraft's LKP. Surface debris was found slightly southwest of the LKP. Search efforts were focused in the areas with the greatest concentration of surface debris. It became evident to the first responders that the extensive destruction of the aircraft left little hope for survival of the occupants.

Video – Wreckage retrieval

Operational phases

The DND quickly developed Operation Persistence, an operational response plan for their support activities. This plan became the framework for resource planning and SAR coordination, and for the early recovery activities of the other agencies. Investigation activities were conducted by three agencies: the OCME, the RCMP, and the TSB. In fulfilment of their SAR responsibilities, the DND took the lead role for the initial overall maritime response. With input from the investigative agencies, senior DND staff directed the planning and coordination of resources to meet the needs of the various parties involved in the initial sea recovery operations. Daily coordination meetings were held in the MOC to ensure that information was exchanged among all parties, and to ensure that priorities and issues raised by all parties were addressed. Once it was determined that there were no survivors, the TSB, the RCMP, and the OCME jointly established priorities for the early wreckage recovery. The DND adopted a coordination role, providing personnel, equipment, logistical and organizational support to the investigation agencies.

Operation Persistence was divided into six phases, as outlined below. These phases, while developed under the auspices of the military plan, remained the framework under which all site operations were completed.

- Phase I: SAR

- Phase II: Initial search and recovery

- Phase III: Deliberate search

- Phase IV: Deliberate recovery

- Phase V: Heavy lift

- Phase VI: Site cleanup

Phase VI, Site Cleanup, was coordinated and contracted by the TSB. This phase was primarily completed by civilian companies contracted to accomplish the work under the direction and control of the TSB and the RCMP. The Canadian Forces, the CCG, and the RCMP maintained a secure exclusion zone for this period.

Phase I: SAR

Recovery methods and operations

When SR 111 disappeared from radar, the Moncton ACC advised the Halifax RCC. The RCC subsequently assigned SAR resources from the DND and the CCG. The Moncton ACC also tasked a civilian aircraft that was in the area to fly over the LKP within minutes of the accident.

An intense search was conducted through the night as more search resources from the DND, the CCG, and local fishers arrived on the scene. The search was focused in areas in which the surface debris appeared to be concentrated. It was determined that these areas were considerably west of the actual location of the aircraft at the time of impact. The amount of debris in those areas was attributed to debris that had surfaced from submerged wreckage and drifted away from the accident site as a result of prevailing water currents.

Personnel

An on-scene advisory group was formed and deployed to assist field operations. The group included the following four members:

- The TSB SGC, a scuba diver and SSS, and underwater acoustic locating equipment operator.

- A DND officer (Navy), a clearance diver and Commanding Officer of the FDU(A).

- Two members of the RCMP, one assigned to escort and security duties for transporting the aircraft flight recorders, if and when they were recovered; and a scuba diver in charge of a URT.

All members had significant underwater search and salvage experience. As no member of the OCME was available to join the group, it was agreed that the OCME would be consulted for input on issues as required. The group was named "G3" to reflect the membership of representatives from the three government agencies represented. The G3 provided a single point of contact to ensure that technical input could be rapidly obtained in an integrated manner from representatives of the government investigative agencies and the DND. The G3 addressed a myriad of investigation issues aimed at optimizing search techniques and diving operations.

Phase II: Initial Search and recovery

Recovery methods and operations

During the first days after the accident, the search for the aircraft wreckage was concentrated in those areas with the greatest concentration of surface debris. As both aircraft flight recorders, the CVR and the FDR, were fitted with ULBs, an underwater acoustic search was implemented to locate them. The HMCS Okanagan, a Canadian Forces submarine, was assigned to supplement the acoustic search on 3 September 1998. This proved a difficult task in some locations owing to factors such as rock outcrops, which created shallow water regions that posed navigation hazards. The shallow water areas were often noisy environments that reduced signal detection ranges, making signal analysis difficult. These areas also created potential signal blind spots. Because it was focused in areas with the greatest concentration of surface debris, the search was initially unsuccessful. It was during transit away from this area on 5 September that the submarine detected a ULB acoustic signal and accurately established the flight recorders' probable location. Upon reception of the ULB signal, navy divers were rapidly outfitted with CUMA diving equipment and deployed to the identified location.

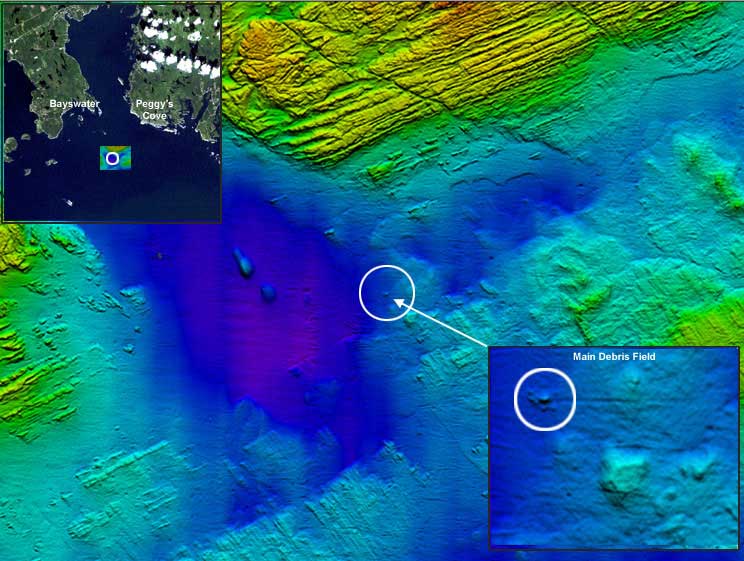

Detailed underwater mapping was conducted to locate all parts of the aircraft. The seabed beneath the aircraft track was subsequently searched by use of scanning equipment and divers to determine whether any debris had fallen from the aircraft. The size of the search area and the nature of the ocean bottom posed several challenges, and required the use of specialized equipment.

The Remote Sensing Group, Emergencies Sciences Division, EC, conducted several tasks, including searching for and analyzing fuel slicks on the ocean. The release of fluids from the wreckage, such as fuel, would help identify the location of submerged debris. This information, gathered by a Convair 580 aircraft and a Douglas DC-3 aircraft outfitted with airborne scanning equipment, was used to help assess whether the aircraft had crashed at a single point of impact, or whether it had broken up in stages and had been deposited over a larger area.

The coastal land areas that the SR 111 aircraft had overflown were also searched for parts that might have been shed from the aircraft and also for evidence of jettisoned fuel. An investigation of the jettisoned fuel was initiated since the flight recorders had ceased to function approximately six minutes prior to impact and it was unknown whether the aircraft had dumped fuel. Stereo aerial survey photographs (near-colour infrared and panchromatic) were taken to search for potential evidence of vegetation stress from the effects of fuel deposits or as a consequence of fallen parts. These photographs were also taken to help assess witness vantage points, and for the potential creation of orthophotomaps for land search operations. SPOT satellite imagery of the scene was also obtained for this purpose. All site information was input and related to other data in the TSB GIS.

The CUMA divers precisely homed in on the ULBs, which although battered, had remained attached to the flight recorders. Owing to the ocean depth and other factors, dive times were restricted to approximately 10 minutes. In addition to being arduous, the task was also dangerous. The dives were conducted in cold water, in low light, and among entangled piles of aircraft debris with many protruding, razor-sharp edges.

Equipment

The HMCS Okanagan provided an efficient means of sweeping large areas where sufficient water column depth permitted.

The CUMA diving set is a lightweight, closed-circuit re-breather system that produces few bubbles. The CUMA set allowed the divers to quickly conduct relatively deep dives with reduced risk of decompression illness. The set also allowed divers to dive again after only a few hours, a much shorter decompression time than that required by traditional equipment. The CUMA divers used portable, hand-held underwater acoustic locators to precisely home in on the ULBs.

Features such as the irregular topography of the ocean floor and rock outcrops and cobble caused aircraft debris to blend into its surroundings when viewed using conventional sonar search equipment. To optimize detection, assist in target classification and identification, and rapidly sweep areas efficiently, equipment such as dynamically-focused, multi-beam, SSS equipment was used at high-tow speeds. This equipment provided large area coverage with superior resolution and image clarity. This information was integrated with a high-resolution, multi-beam echo system that generated a detailed three-dimensional bathymetry model of the ocean floor. Differential satellite global positioning systems were used for accurate navigation and surveillance. The high-resolution, SSS and bathymetry data formed the foundation upon which all ongoing and future underwater operations were conducted. Computer modelling for ocean currents at various depths in the water column was also used to supplement this data. This modelling was used to help determine the origin and destination of surface debris. A DTM of the ocean floor and coastal land areas was ultimately created, related, and compiled with other important information into the TSB GIS.

The Convair 580 aircraft was used to quickly search the ocean surface for fuel slicks using Synthetic Aperture Radar. Synthetic Aperture Radar, an active sensor, generated images that allowed searching for debris and slicks day or night, through fog and bad weather, as required. The specially equipped, slower flying Douglas DC-3 aircraft worked in concert with the Convair 580 aircraft. When the Convair 580 aircraft detected a slick, the DC-3 was dispatched to analyze the slick using an on-board LEAF. The LEAF was used to determine whether the slick was an unrelated pollutant, such as fuel from a ship (Bunker C fuel), or whether it was related to the missing aircraft (Jet A fuel). This information was also supplemented by Synthetic Aperture Radar imagery of the scene obtained from Canada's RADARSAT satellite. These aircraft were also used to search for shed aircraft parts and evidence of jettisoned fuel, and to take stereo aerial survey photographs.

Phase III: Deliberate search

Recovery methods and operations

The recovery of human remains was a high priority throughout the entire search phase. This effort was sustained along with other search and recovery objectives in the following areas:

- Debris field, particularly in the identified location of the flight recorders

- Final flight track

- General search area surrounding the LKP

- Areas where wreckage was anticipated to drift

- Shoreline

- Areas in which witnesses believed that the aircraft had flown or that flight evidence might exist

In addition to the deployment of SSS equipment for the search and area mapping on 3 September 1998, the search included the following ongoing activities:

- Surface search by Navy, RCMP, CCG and auxiliary vessels

- Surface and shoreline search by military and CCG helicopters

- Shallow water (coastal diving) searches by RCMP and military divers

- Shoreline search by military and volunteer land search team members

Equipment

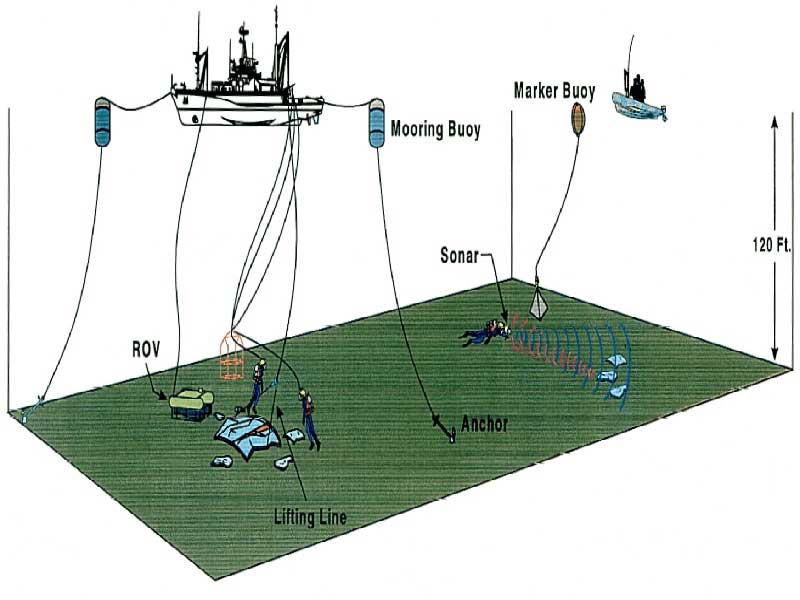

Canadian naval divers switched from CUMA-equipped diving to surface-supplied diving on 9 September 1998 to allow for greater time on the bottom. ROVs were also deployed from two ships for searching and conducting very limited recovery operations; their recovery capability was restricted by their limited lift capabilities. Initially, these ROVs did not have a navigation or positioning system to provide accurate positioning information when a target was found. Navigation positioning systems were subsequently purchased and the ROVs were modified.

Phase IV: Deliberate recovery

Recovery methods and operations

The following four methods were first used to locate and collect wreckage outside the main debris area:

- Surface and shore retrieval

- SCUBA-facilitated searches (in coastal areas)

- Shallow water, CUMA, and surface-supplied diving searches

- ROV searches

Owing to the water depth at the wreckage site, the limited deep-water recovery and salvage capability available, and the limited time frame within which recovery operations could be conducted before the North Atlantic storm season made recovery operations impractical, it soon became evident that additional recovery equipment would be required. The USN provided a salvage vessel of similar capability to that used in the TWA 800 wreckage recovery; the USS Grapple was assigned to assist. The ship arrived in Halifax on 11 September 1998, was prepared for sea, and began on-site operations on 14 September 1998.

The TSB also requested the use of the USN LLS equipment. This equipment, however, could not survey the site effectively at the depth required. As a result, it was decided to proceed with the recovery operation and conduct a sea bottom survey when other LLS equipment was available. Targets were identified and recovered using divers and ROVs. Canadian Forces divers were deployed alongside the USS Grapple. ROV and diver-helmet camera information was used to make technical assessments during this phase.

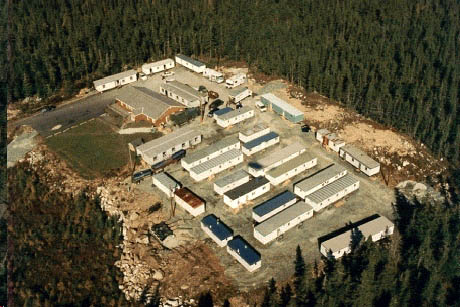

On 3 September 1998, 12 Wing Shearwater provided two hangars: "A" Hangar and "B" Hangar. "A" Hangar was used for the reception and sorting of aircraft debris, while "B" Hangar served as a temporary morgue.

Recovered aircraft debris was transported to the HMCS Preserver and then transferred to a jetty in Shearwater using CCG ships. Most of the material recovered early in the process consisted of surface debris, predominantly aircraft interior items and a few personal effects. Once on site, the USS Grapple began the recovery operation. After a preliminary freshwater rinse, the recovered wreckage was transported directly to the jetty at 12 Wing Shearwater by CCG ships. The material was received at the jetty in 12 Wing Shearwater, freshwater washed, and transported to "A" Hangar for identification, sorting, and storage and material layout.

Recovered human remains were transported to the HMCS Preserver, transferred to DND Sea King helicopters, and then flown to "B" Hangar.

While the USS Grapple was moored over the main debris pile, the CCGS Matthew conducted an SSS search of the flight track the aircraft had flown just prior to the crash to determine whether there was any aircraft debris in these areas. No debris was recovered.

On 30 September 1998, the USS Grapple left its moorings over the wreckage site and prepared for its return to the United States.

Personnel

Approximately 150 Canadian DND and RCMP divers and 20 USN divers worked together during this phase. To assist in identifying debris targets, specialists from the TSB and selected advisors and observers were on board ships.

Phase V: Heavy lift recovery operations

Recovery methods and operations

After exploring several options for a higher volume method of recovery for the substantial amount of remaining wreckage, it was decided to contract a lifting vessel that used a large bucket to capture the aircraft wreckage from the underwater debris pile and lift it onto a barge moored alongside. The material was then freshwater washed, sorted, and transported to 12 Wing Shearwater on a CCG ship.

Equipment

A contract was let for the lifting ship, the Sea Sorceress, and a barge to be used as a platform to receive, wash, and sort the material. The Sea Sorceress used a dynamic positioning system to optimize its lift over the debris field. The ship also had an on-board ROV used to assess coverage and lifting effectiveness. A CCG ship, the Earl Grey, was used to transport the recovered material to Shearwater for further processing and examination.

Personnel

An officer from the CCG with salvage experience acted as project manager. The labour-intensive requirements of the effort required nine 10-person teams of RCMP, DND, and TSB personnel to support the 24-hour, 7-day-per-week operation. These teams were housed and supported ashore in a temporary base camp that allowed them to transfer to and from the barge before and after each shift. These support facilities were erected adjacent to a community centre in Blandford, Nova Scotia, by DND personnel in a matter of weeks. This operation was supported by many other companies and agencies, including local firefighters.

TSB on-site coordinators remained on board the Sea Sorceress throughout the operation. The teams were transported for each shift by a small "taxi" craft that had been used to transport personnel during the construction of the Confederation Bridge. Approximately 1 000 transfers of people onto the barge were conducted during this phase of recovery operations. Facilities to support the teams (medical, food, decontamination, rest areas, etc.) were located on the barge. Recovered items were rinsed, sorted, prioritized, and prepared for shipment ashore in the wreckage reception area on the barge.

Phase VI: Site cleanup and recovery operations

This operational phase was divided into the following chronological subphases:

- Scallop dragger operation

- Site security, survey, and specialized recovery

- Accident survey

- Wreckage recovery using CFAV Endeavour and DSIS ROV

- Suction hopper dredging

- Debris sifting

Scallop dragger operation

Recovery methods and operations

The TSB contracted the Anne S. Pierce, a commercial scallop dragging ship owned and operated by Clearwater Fisheries, to recover aircraft wreckage from the ocean floor using a scallop drag net. Operations were conducted in the accident site area from 6 November 1998 to 12 January 1999. The crew sorted the debris as it was brought aboard after each drag.

The winter weather and the high sea state limited the operation. These conditions, compounded by low temperatures and high winds, caused ice to form on deck making on-deck activity hazardous. In sea swells of 3 m or more, the drag net, suspended above the deck, swung unpredictably.

Personnel

Two TSB technical investigators and two members of the RCMP were aboard the Anne S. Pierce to provide technical investigation direction to the crew and to arrange for the appropriate treatment of sensitive debris, such as high-priority items of significant interest to the investigation, personal effects, and human remains. All aspects of the vessel operation and handling were carried out by the contracted 11-person fishing crew.

Equipment

The scallop drag net had an average opening of 2.5 feet below the rake and a chainmail net consisting of 3.5-inch rings (later modified to 2-inch rings) connected by 2-inch links. Fish tubs were used to store and transport the debris. Small tote boxes were used to transfer smaller debris.

Site security, survey, and specialized recovery (CCGS Parizeau)

Recovery methods and operations

Beginning in mid-February and continuing until the end of March 1999, the CCGS Parizeau, equipped with "Videograb" equipment from the BIO and a small ROV from the DREA, collected site security and camera survey information about the debris field.

Personnel

Along with CCG personnel, members of the RCMP and TSB investigators were on board during these operations.

Accident site survey

Recovery methods and operations

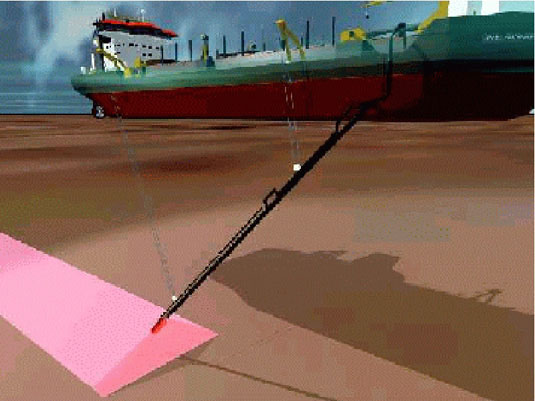

The TSB engaged CSR to carry out an LLS and an SSS survey of an area about 1 sq. nm around the accident site. The survey was conducted using the CCGS Earl Grey between 16 and 30 November 1998. Survey operations were conducted on a 24-hour basis, stopping only for inclement weather or mechanical failures. All activities pertaining to the safe operation and handling of the vessel and equipment were carried out by the CCG.

CSR developed the survey plan based on a 1 sq. nm box surrounding the main debris area. The survey box was oriented so that the grid lines ran southwest to northwest and were spaced at 10 m intervals.

It became apparent that the survey could not be completed within the allotted time frame owing to deteriorating weather. As a result, the survey focused on obtaining as much LLS information as possible within the main accident site and only sampled some peripheral areas. Because the SSS equipment could effectively survey a larger area than the LLS, grid lines were selected to allow the SSS to cover 100% of the survey area in the allotted time.

The equipment's capability to provide high-quality data was severely limited by the weather. If the sea swells exceeded approximately 2 m, the movement of the ship made it difficult for the towed equipment to maintain a steady altitude above the sea bottom. Turbidity in the water resulting from storms and tidal movement, caused a dramatic reduction in the image resolution and quality. Wind also made it difficult to maintain the ship on a straight course.

Equipment

CSR supplied the survey equipment. All LLS imaging was recorded on videotape and the individual targets were captured as unique "frame grabs." All target locations were recorded and plotted onto either the side-scan mosaic or multi-beam background. The SSS was set to a 50 m range on each side and the captured data was available as individual line printouts or a complete mosaic.

Personnel

The LLS and the SSS survey were conducted by CSR operating personnel. Two TSB technical investigators were also deployed on board the ship to provide direction and guidance to CSR, as well as to monitor the data as it was being collected.

Wreckage recovery using CFAV Endeavour and DSIS ROV

Recovery methods and operations

The wreckage and recovery operation using the CFAV Endeavour and DSIS ROV commenced on 26 April 1999 and continued until 14 July 1999.

The results of previous operations indicated that most of the remaining debris lay in an area identified as the main debris field, an area surrounding the main wreckage site that was 50 m wide north to south and 125 m long east to west. Based on visual information gained from the previous operations, the team focused on clearing the main debris field of all visible debris and then expanded this operation to the surrounding area.

Equipment

The DSIS ROV, owned and operated by the Canadian Forces FDU(A), was used to recover aircraft wreckage from the ocean floor.

The CFAV Endeavour was leased for use as the operating platform. A smaller Phantom ROV was used as a survey and backup vehicle.

To recover the smaller pieces, the team designed and built a basket that was carried by the DSIS manipulators. The basket had a lid to securely contain the buoyant materials. Midway through the operation it was decided that only debris larger than 30 cm (long or wide) would be retrieved since the draghead on the Queen of the Netherlands, the dredge ship that was intended to be used in the final recovery operation, was equipped with an integral screen that would prevent the retrieval of anything larger than 30 cm.

Personnel

The DSIS was deployed with six operating support personnel from the FDU(A) and three FSRs providing maintenance support from ISE. Two persons captured historical data of all subsurface operations in the form of maps and electronic data. A member of the RCMP was on board to secure the exclusion zone and to process recovered exhibits. A TSB investigator was also on board to serve as the coordinator and liaison for prioritizing recovery efforts and activities at sea, as well as to provide technical advice for handling all aircraft wreckage pieces.

Suction hopper dredging

Recovery methods and operations

In March 1999, the TSB assessed various options to complete the site cleanup. It was discovered that the trailing suction hopper dredge, the QN, would be operating in Canadian waters at Terra Nova as part of the Petro-Canada Terra Nova Project. The QN's technology allows it to retrieve vast quantities of material from water depths of up to 140 m in a remarkably short time period. The Dutch firm Boskalis made the vessel available under contract near the end of September.

After undergoing three days of equipment modifications in St. John's, Newfoundland, the QN departed at 0800ADT (1100 UTC) on 26 September 1999 and arrived at the accident site at 2000 ADT (2300 UTC) on 27 September 1999. Extensive video coverage of the main wreckage field showed a seabed characterized by loose glacial silt, sand, and gravel. Seabed samples from this area showed aircraft debris intermixed with the loose bottom material, but not within the underlying clay bed. The dredging operation was subsequently focused on recovering only the loose materials. To this end, the bottom was dredged using a "sawing" method in which the ship first makes a single pass and then repositions itself for repeated parallel passes.

The main debris area was dredged four times, to a depth of approximately 1.5 m. A video survey of this area showed little remaining debris. The adjacent secondary area, slightly east of the main area, was dredged twice to a depth of approximately 30 cm. A video survey of this area showed little disturbance to the seabed and no remaining debris. An adjacent tertiary area farther east consisted predominantly of bedrock. As the dredging operation proved ineffective in this area, it was only slightly dredged and was considered a lesser priority than the primary area. Dredging was stopped when the ship reached its maximum draft (i.e., water depth drawn by the ship when loaded), having collected approximately 8 500 m³ of recovered material.

Dredging and pre- and post-dredge surveys were carried out on 28 and 29 September 1999, recovering approximately 8 500 m³ of material. Upon completion of the final survey, the dredged material was transported aboard the QN to the Sheet Harbour Industrial Port, Nova Scotia. This site was chosen to offload the dredged material owing to the appropriate depth of the harbour and the availability of a suitable containment area. A 2.5 m high containment dyke, fitted with an approved environmental liner and with an overall capacity of approximately 50 000 m³, was constructed on a five-acre site adjacent to the harbour. The construction of the dyke and sifting area and the supply of equipment and personnel were contracted through PWGSC to Dexter Construction. The QN arrived alongside the dock at 0830 ADT (1130 UTC) on 30 September 1999 and commenced offloading. Offloading continued for the next 26 hours, during which time all possible material was discharged. At this time, members of the RCMP and TSB personnel took a visual survey of the vessel's hopper and determined that no items of interest to the investigation remained.

Debris sifting

Recovery methods and operations

The initial sifting and sorting of the dredged material was carried out at the Sheet Harbour site using various pieces of heavy equipment. On 5 October 1999, the TSB and contracted Dexter personnel collected all visible aircraft debris and personal effects from the surface of the material in the dyked areas. The remaining material was processed using mechanical screening equipment that separated the aircraft debris from most of the natural seabed or waste material. The non-waste material was moved from the separator on a conveyer belt, where contract personnel retrieved and sorted the items. This sifting operation started on 6 October 1999 and continued until 2 November 1999, when all of the dredge materials had been processed.

Site security was provided by the RCMP and consisted of an 8-foot wire fence with a single point of entry surrounding the entire dyke and sorting area. Video cameras mounted at key locations within the dyke and sorting areas, as well as on both of the conveyor systems, allowed the RCMP to monitor all activities.

Summary

The depth of the water and the undetermined point of impact in the initial stages of the search and recovery phase created substantial challenges. Despite these challenges, the high degree of cooperation and innovation, the multitude of available and effective resources, and a systematic and sustained approach lead to remarkable results. The early recovery of the flight recorders was a substantial accomplishment and significant milestone in the investigation. Extraordinary efforts by the dive teams sustained the recovery of human remains for the maximum possible time, which ultimately contributed to the successful identification of all those on board SR 111. During many of these activities, search and recovery personnel faced great challenges and uncommon personal risk. The operations were nevertheless completed without any serious injury.

Despite new recovery challenges at each operational phase, almost 98% of the aircraft's structural weight was recovered.

Investigation participants and roles

| Agency | Role(s) |

|---|---|

| TSB | Lead agency Accident and safety investigations (in accordance with ICAO SARP Annex 13) Custodian of aircraft accident evidence Coordination of activities |

| RCMP | Co-lead agency Criminal investigation Recovery Victim identification Custodian of personal evidence Victims services assistance (support to families) Support to the OCME Support to the TSB |

| CF | SAR Search and recovery Command and coordination Facilities and logistical support Site security |

| DFO CCG BIO MSEP |

SAR Search and recovery Coordination Reconnaissance Marine transport services Site security Underwater surface imaging |

| Nova Scotia OCME | Identification and control of human remains Liaison with victims' families |

| USN | Search and recovery (USS Grapple) |

| EPC | Federal agency coordination |

| Nova Scotia OCME | Provincial agency coordination |

| Health Canada | Critical incident stress counselling and support |

| TC | Minister's observer |

| Swissair (Aircraft Operator) |

Family assistance Component and wreckage identification Advisor to Swiss AAIB Accredited Representative |

| SR Technics (Swissair's Aircraft Maintenance Organization) | Component and wreckage sorting and identification Advisor to Swiss AAIB Accredited Representative |

| Boeing Company (aircraft manufacturer) | Component and wreckage recovery, sorting, and identification Advisor to the NTSB Accredited Representative |

| NTSB (US) | Accredited Representative (State of Manufacture) Wreckage recovery and sorting assistance |

| AAIB (Switzerland) | Accredited Representative (State of Registry) |

| Nova Scotia Department of Transportation and Public Works | Logistics and specialist support |

Main equipment assets

| Equipment/Resource | Services |

|---|---|

| CCGS Edward Cornwallis (major navaids tender) |

Search and recovery Small boat coordination Exclusion zone enforcement |

| CCGS Simon Fraser (medium navaids tender) |

Inshore search and recovery Side boom net operations Exclusion zone enforcement |

| CCGS Earl Grey (medium navaids tender) |

High resolution LLS SSS Debris transportation |

| CCGS Mary Hichens (large SAR cutter) |

Diving support Debris transportation |

| CCGS Matthew | Bottom survey/mapping Located wreckage Marine accommodation |

| CCGS Hudson | LLS |

| CCGS Sambro (SAR lifeboat) |

Recovery operations Exclusion zone enforcement |

| CCGS Frank M. Weston (utility vessel) |

Inshore recovery operations Exclusion zone enforcement |

| CCGS Northbar (utility vessel) |

Recovery operations Exclusion zone enforcement |

| CCGS Alfred Needler (fishery research vessel) |

Trawl operations |

| CCGS Parizeau | Bottom surveys Reconnaissance ROV/Video Site security |

| MBB 105 helicopters (utility helicopters) |

Search Transportation Surveillance flights |

| Equipment/Resource | Services |

|---|---|

| Barge ATL 2401 | Heavy lift operation |

| Sea Sorceress (salvage ship) |

Heavy lift operation |

| Anne S. Pierce (scallop dragger) |

Dragging operations |

| Queen of the Netherlands (suction hopper dredge ship) |

Dredging operations |

| Equipment/Resource | Services |

|---|---|

| HMCS Preserver (operational support ship) |

On-scene command SAR Initial response |

| HMCS Halifax (patrol frigate) |

On-scene command (11 to 30 September 1998) |

| HMCS Ville de Quebec (patrol frigate) |

SAR Initial response |

| HMCS Okanagan (submarine) |

Sonar |

| HMCS Moncton (maritime coastal defense vessel) |

SSS/ROV Bottom search and survey |

| HMCS Goose Bay (maritime coastal defense vessel) |

SSS Bottom search and survey |

| HMCS Glace Bay (maritime coastal defense vessel) |

SSS (SQS 511) |

| HMCS Kingston (maritime coastal defense vessel) |

SAR SSS/ROV Bottom search and survey Sea floor mapping |

| HMCS Anticosti (coastal auxiliary vessel) |

ROV Bottom search and survey |

| CH-124 Sea King (maritime helicopters) |

Search/surveillance Utility transportation |

| CH-113 Labrador (SAR helicopters) |

SAR |

| CH-146 Griffon (utility helicopters) |

Coastal search Utility transportation |

| CP-140 Aurora (maritime patrol aircraft) |

Surveillance flights |

| CC-130 Hercules | SAR |

| YDT Granby (diving tender) |

Surface-supplied diving CUMA |

| YDT Sechelt (diving tender) |

Surface-supplied diving CUMA |

| CFAV Endeavour (auxiliary vessel) |

ROV |

| CFAV Glenevis (tug) |

Search and recovery |

| SQS 511 route survey SSS | Bottom mapping Search and location |

| DSIS/ROV | Locate and retrieve |

| Phantom ROVs | Locate and recce |

| A and B Hangars (12 Wing Shearwater) |

Wreckage storage and sorting Morgue |

| Land Forces | Land Force Area Atlantic HQ 1st Combat Engineer Regiment 2nd Combat Engineer Regiment 2nd Field Engineer Regiment Land Force Area Quebec HQ 1st (Halifax Dartmouth) Field Artillery 1st Battalion Nova Scotia Highlanders 2nd Battalion Nova Scotia Highlander 2nd Battalion The Royal New Brunswick 2nd Battalion Royal Canadian Regiment 3rd Field Artillery Regiment RCA 31st (Saint John) Service Battalion 33rd (Halifax) Medical Platoon 33rd (Halifax) Service Battalion 35th (Sydney) Medical Company 35th (Sydney) Service Battalion 36th Canadian Brigade Group HQ 4th Air Defense Regiment RCA 4 Air Defense Regiment Detachment 4th Engineer Support Regiment 45th Field Engineer Squadron 5th Combat Engineer Regiment 8th Canadian Hussars (Princess Louise's) Combat Training Centre HQ Defence and Civil Institute of Environmental Medicine Prince Edward Island Regiment Princess Louise's Fusiliers West Nova Scotia Regiment |

| Canadian Forces Medical Units | CF Medical Group HQ D Dental SVCS 1st Dental Unit HQ 1st Dental Unit Detachment Valcartier 1st Dental Unit Detachment Gagetown 2 1st Dental Unit Detachment Greenwood 1st Dental Unit Detachment Halifax 13th Dental Unit Detachment Petawawa |

| Simmonds | Shallow water diving operations |

| Klein 5000 SSS | Bottom search and survey Sea floor mapping |

| USS Grapple (salvage ship) |

Diving/ROV Reconnaissance Recovery |