Grounding

Passenger vessel Clipper Adventurer

Coronation Gulf, Nunavut

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

On 27 August 2010 at approximately 1832 Mountain Daylight Time, the passenger vessel Clipper Adventurer ran aground in Coronation Gulf, Nunavut while on a 14–day Arctic cruise. On 29 August, all 128 passengers were transferred to the CCGS Amundsen and taken to Kugluktuk, Nunavut. The Clipper Adventurer was refloated on 14 September 2010 and escorted to Port Epworth, Nunavut. There was minor pollution and no injuries.

Factual information

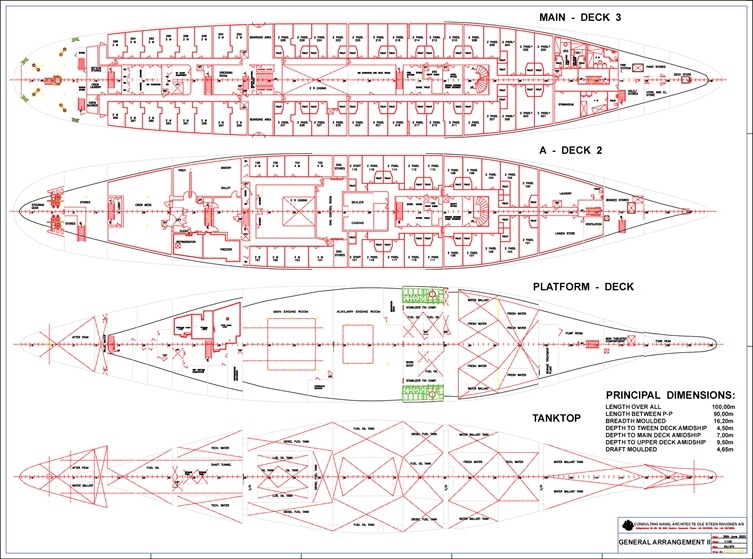

Particulars of the vessel

| Name of vessel | Clipper Adventurer |

|---|---|

| Official number | 730585 |

| Port of Registry | Nassau |

| Flag | Bahamas |

| Type | Passenger |

| Gross tonnage | 4376 |

| LengthFootnote 1 | 90.91 m |

| Draught | Forward: 4.5 m Aft: 4.6 m |

| Built | 1975, Kraljevica, Yugoslavia |

| Propulsion | 2 x B & W 3884 kW, twin propellers |

| Passengers | 128 |

| Crew | 69 |

| Registered owner | Adventurer Owner Ltd., Nassau, Bahamas |

| Manager | International Shipping Partners, Inc., Miami, Florida, United States |

| Charterer(s) | Adventure Canada Ltd., Mississauga, Ontario |

Description of the vessel

The Clipper Adventurer is of typical passenger vessel construction with the superstructure extending the entire length of the vessel abaft a short foredeck. The vessel has an ice–strengthened hull. The vessel has 2 controllable–pitch propellers and 2 semi–balanced articulated flap rudders for improved vessel manoeuverability. The navigation bridge is situated at the forward end of the superstructure. The navigational equipment is comprised of 2 radars, 2 Electronic Chart Systems (ECS), 2 Global Positioning Systems (GPS), 1 echo–sounder, a NAVTEX, and a GMDSSFootnote 2 station with Inmarsat–C Enhanced Group Calling (EGC). The Clipper Adventurer is also fitted with a forward looking sonar mounted on the head of the bulbous bow; however, it was unserviceable at the time of the occurrence. Since 1998, the Clipper Adventurer has been extensively used in adventure cruises.

Voyage planning

According to the International Maritime Organization (IMO),Footnote 3 a voyage plan, or passage plan, should be completed by all vessels. It consists of 4 stages:

- Appraisal of all the available information about the intended voyage, including a review of the charts and publications, prediction of the vessel's condition, assessment of the dangers expected, gathering of information about the local weather and environmental conditions and noting of how to obtain weather forecasts and local warnings while en route.

- Planning of the intended voyage including no–go areas and areas where special precautions must be taken.

- Execution of the passage plan, taking into account the prevailing conditions.

- Monitoring of the vessel's progress against the intended plan continuously throughout the voyage, including gathering the pertinent local warnings for the intended voyage.

The IMO has further recognized that ships operating in the Arctic and Antarctic are exposed to a number of risks such as poor weather conditions and that the relative lack of good charts, communication systems, and other navigational aids pose a challenge for mariners.Footnote 4 In November 2007, the IMO adopted the resolution Guidelines on Voyage Planning for Passenger Ships Operating in Remote Areas. These guidelines indicate that the voyage planning should take into account the source, date and quality of the hydrographic data of charts used; safe areas; no–go areas; surveyed marine corridors if available; and contingency plans for emergencies in the event of limited assistance being available in areas remote from SAR facilities.

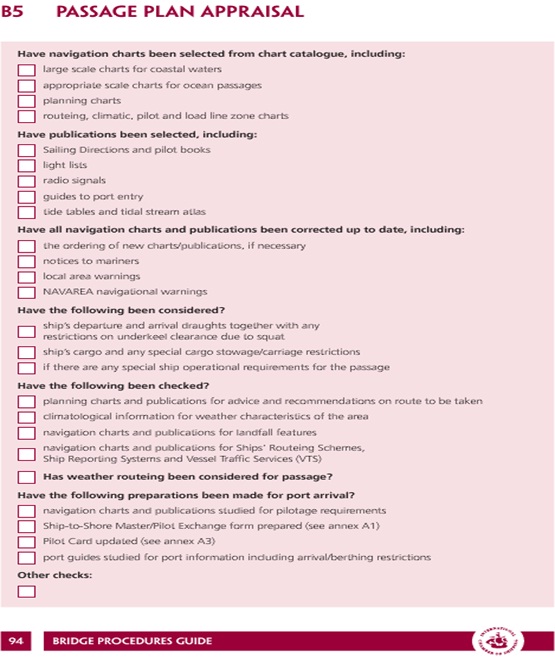

Based on IMO Resolution A893(21) and SOLAS,Footnote 5 the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) produced the Bridge Procedures Guide.Footnote 6 This publication provides valuable guidance for bridge teams and indicates that, before voyage planning can commence, a passage plan appraisal is to be completed that includes gathering and studying the charts, publications, and other information appropriate for the voyage. Only official nautical charts and publications are to be used for voyage planning and must be corrected to the latest available Notices to Mariners (NOTMAR) and local area warnings. In addition, the Canadian Charts and Nautical Publications Regulations, 1995 and, in particular, section 7 reads as follows:

The master of a ship shall ensure that the charts, documents and publications required by these Regulations are, before being used for navigation, correct and up–to–date, based on information that is contained in the Notices to Mariners, Notices to Shipping or radio navigational warnings.

One of the Clipper Adventurer management company's procedural manuals pursuant to its Quality, Safety, and Environmental Management System (QSEP manual 3) concerns vessel operations and provides the following guidance to the master and bridge team for voyage planning:

- The master has an overall responsibility for the implementation of the Quality, Safety, and Environmental Protection (QSEP) program on the vessel. He has to ensure that a passage plan is prepared from berth to berth.

- The passage plan should be made in accordance with the ICS Bridge Procedures Guide.Footnote 7

- Prior to departure, the navigation officer has to prepare a passage plan and verify that the navigation equipment is tested and ready. The officer must ensure availability of charts for the voyage and that these charts are corrected to the latest NOTMAR. The officer must attach any other temporary navigation warnings to the charts.

- The Clipper Adventurer was to carry Transport Canada's (TC) Guidelines for the Operation of Passenger Vessels in Canadian Arctic WatersFootnote 8 on board. The Guidelines observe that waters north of 60° N are not well surveyed and soundings in many areas are based on reconnaissance surveys and are not up to international standards. They also refer to Canadian Notices to Shipping (NOTSHIPs) indicating that they are broadcast by Marine Communications and Traffic Services (MCTS).

In October 2009, the Clipper Adventurer was chartered for the Arctic 2010 cruise season by a Canadian adventure tour company. According to the agreement, the vessel was to be managed by a ship management company based in the United States. Voyage planning, including the choice of sailing routes between destinations, was the responsibility of the master and his bridge team.

During the winter before the scheduled cruise, the Clipper Adventurer's navigation officers and the charterer prepared an itinerary. The initial itinerary did not include Port Epworth, a geological point of interest. On 23 February 2010, the charterer requested that the itinerary be modified to include a stop in Port Epworth on day 14 of the cruise. On 08 May 2010, a modified itinerary was circulated by email to the charterer, master, and ship management company. On 03 August 2010, the navigation officer (second officer) completed the ship management company's Voyage Planning FormFootnote 9 which was subsequently signed by the master and the bridge team. This 1–page form included a list of waypoints, courses, distances between waypoints, and the under–keel clearance for each leg of the voyage, including the passage from Port Epworth to Kugluktuk. Publications for the intended voyage were listed on the form, including the following to be used when operating in polar waters:

- IMO A 26/Res. 1024 – Guidelines for Ships Operating in Polar Waters

- MSCFootnote 10 1/Circ. 1184 – Enhanced Contingency Planning Guidance for Passenger Ships Operating in Areas Remote from SAR Facilities

- IMO A 25/Res. 999 – Guidelines on Voyage Planning for Passenger Ships Operating in Remote Areas

- MSC 1/Circ. 1185 – Guide for Cold Water Survival

However, the 1–page form did not indicate that the 4 stages of voyage planning were completed by the bridge team, nor did it contain information indicating that the ICS Bridge Procedure Guide was used as a guideline for the voyage planning, as referenced in the company QSEP. The completed form does not indicate that the bridge team complied with the company QSEP, nor does it indicate that the team used the voyage planning appraisal form from the ICS Bridge Procedures Guide. The Bridge Procedures Guide lists voyage planning steps including the requirement to access local marine safety information and local warnings (Appendix B).

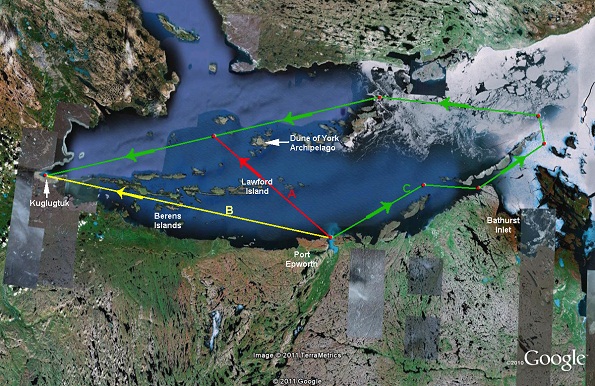

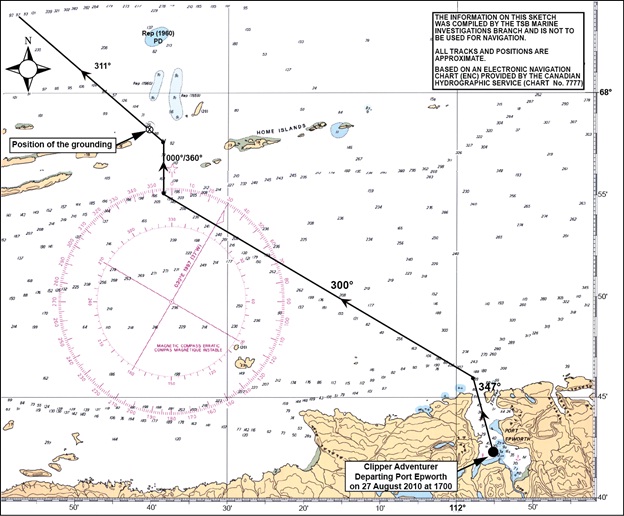

The master and bridge team considered two routes from Port Epworth to Kugluktuk. The first (A) was a course north from Port Epworth, crossing an archipelago on a single line of soundings before proceeding west parallel to the islands, also on a single line of soundings. A second option (B) of proceeding west between the southern shoreline of Coronation Gulf and the archipelago using a single line of soundings was also considered.

Subsequently, in Port Epworth, a third alternative route (C) was available to the bridge team that consisted of using their reciprocal track (which they had already successfully navigated) northeast back to the main east–west surveyed channel. (Figure 1 and accompanying table). The bridge team elected to take the first option (A).

Throughout the voyage planning process, the master and ship management company were aware that the forward looking sonar was not serviceable. Additionally, they did not make plans to use one or more of the vessel's portable echo–sounder equipped inflatables to precede the vessel, a risk mitigation method previously used by the vessel in other unsurveyed areas in the Arctic and Antarctica.

| Route | Approximate distance (nm) | Speed required (knots) | Time required (hours–min) to reach destination (Kuglugtuk, NU) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 90 | 6 | 15h 07 min |

| B | 85 | 6 | 14h 10 min |

| C | 200 | 13 | 15h 23 min |

Forward looking sonar

In 2006, the Clipper Adventurer was equipped with a 3–dimensional forward looking sonar that was fitted into the bulbous bow and was mainly used to determine ice–aging. This unit can be used to detect hazards, notably when operating in inadequately surveyed waters.Footnote 11 The unit enables a range of 330 m with a 90° field–of–view, or 440 m with a 60° field–of–view.

There was a technical problem with the unit in the spring of 2010. The manufacturer worked remotely with the crew to perform some limited analysis of the unit. Subsequently, the Clipper Adventurer was dry docked in Helsingborg, Sweden for bottom painting. At that time, the cable connector on the transducer module (TM) was reported to have been damaged during the dry docking. However, the vessel was refloated and departed for North America with the sonar out of service. This meant that the next opportunity for repair would be after the 2010 Arctic cruise season. The carriage of a forward looking sonar is not mandatory by Canadian Regulations, nor is it a recommended requirement in the IMO Guidelines for Ships Operating in Polar Waters (A26/Res.1024).

History of the voyage

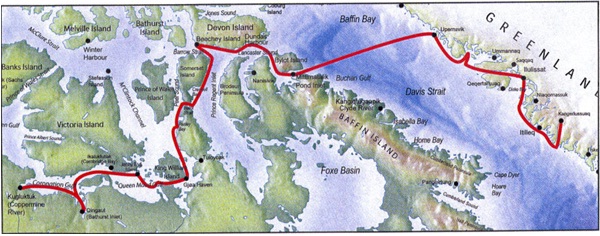

On 14 August 2010, the Clipper Adventurer embarked 128 passengers and departed from Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, bound for Kugluktuk, Nunavut, on a scheduled 2–week Arctic cruise. A bridge watch system of 4 hours on, 8 hours off was shared between the 3 bridge watch officers. There was a quartermaster assigned to each watch who, in addition to his other duties, acted as a lookout. The master's schedule was not fixed since he was required to be available as necessary throughout the voyage. The Clipper Adventurer was transiting in surveyed areas for most of the voyage. On day 13, however, the Clipper Adventurer transited between Bathurst Inlet and Port Epworth, an area that was largely unsurveyed, consisting primarily of single lines of soundings.

On 27 August, the vessel made a port stop in Port Epworth. The vessel was scheduled to complete its itinerary in Kugluktuk at 0800Footnote 12 the next morning. Before departing anchorage, the bridge team prepared courses from Port Epworth to Kugluktuk using Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS) chart No. 7777. The shore excursion to Port Epworth ended and the vessel got underway at 1700, 3 hours ahead of schedule. At the time of departure, the chief officer, quartermaster and master were on the bridge.

Normal practice by the bridge team was to record GPS position on the hour. The position at 1800 was noted in the deck logbook and plotted. Two other positions had also been plotted on the paper chart at 1730 and 1755. The ECS was used by the bridge team to monitor the vessel's progress using a raster navigation chart (RNC) CHS No. 7777.

The chief officer who was in charge of the watch monitored the vessel's progress using parallel indexing on the starboard radar and monitored the water depth on the echo–sounder. The master monitored the port radar when on the bridge. Once clear of Port Epworth and on course 300° gyro, the vessel was placed on autopilot and proceeded at 13.9Footnote 13 knots. The quartermaster remained on the bridge, to take over the steering when required. Shortly after departing Port Epworth, the chief officer marked a depth of 66 m on the chart in an area near where the chart indicated a depth of 40 m.

At 1832, the vessel ran aground on a shoal in position 67° 58.2′ N and 112° 40.3′ W and listed 5 ° to portside. The vessel grounded on hard rock shelf from approximately the forepeak to amidships.

After the grounding, the chief officer stopped the main engines and closed all watertight doors from the bridge. The crew carried out emergency procedures, including sounding the tanks and lowering the lifeboats. Following the sounding of the tanks, the crew reported to the master that 7 tanks/compartments were breached.

At 1853, the master attempted to contact Marine Communications and Traffic Services (MCTS) Inuvik by cell phone, but was unsuccessful. At 1855, the master contacted the company's Designated Person Ashore (DPA) by satellite phone. At 1903, the master sent a marine telex to Northern Canada Vessel Traffic Services Zone (NORDREG) Iqaluit reporting that they had run aground. At 1910, all passengers were mustered to the main lounge and stood down at approximately 2030. At 1915, NORDREG Iqaluit relayed the message to MCTS Inuvik.

Events following the grounding

Master's initial attempts to refloat

On 28 August 2010, at 0055 in Arctic twilight, ballasting of the afterpeak and transferring of fuel between tanks began in preparation for an attempt to refloat the vessel. Between 0205 and 0400, the main engines were operated astern and the bow thruster run as needed in an unsuccessful effort to back off from the shoal. At 0930, a second attempt was made to refloat using the vessel's bow anchors in addition to the engines and bow thruster. This second attempt was also unsuccessful. The management company's emergency response team, which had assembled at the company headquarters upon receiving notification of the grounding from the master, was not made aware of these attempts in advance. During these attempts, the passengers' routine continued as normal. They were not re–mustered but were kept informed of the actions being taken. The management company dispatched a representative to the vessel who arrived a few days later.

During its investigation, the TSB assessed the stability condition of the vessel before grounding, as well as the stability and structural condition during the first attempt by the master to refloat the vessel. The results show that the vessel had sufficient stability to remain afloat and stable if refloating had been successful. The longitudinal bending and shearing stresses did not exceed the allowable residual stresses in the damaged condition.

Search and rescue

On 27 August at 1915, Joint Rescue Co–ordination Centre (JRCC) Trenton was advised of the grounding and initiated an Enhanced Group Calling (EGC) SafetyNet broadcast with distress priority at a 200–mile radius around the Clipper Adventurer. At 1932, the CCGS Amundsen was tasked and underway from Lady Franklin Point towards the grounding site. JRCC initially tasked a Hercules aircraft, with SAR kits on board with an ETA of 3 hours. However, it was stood down when the Clipper Adventurer advised NORDREG Iqaluit, at 1933, that the vessel was not taking on water and was in no immediate danger. At 2151, all broadcasts from MCTS Inuvik and MCTS Prescott via EGC were suspended.

On 29 August at 1000, the CCGS Amundsen arrived on scene and conducted hydrographic surveys of the area throughout to ensure its own safety. The passengers were transferred from the Clipper AdventurerFootnote 14 to the Amundsen and taken to Kugluktuk. All 69 crew members remained on board the Clipper Adventurer. On 29 August, the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier was tasked with assisting with pollution control at the grounding of the Clipper Adventurer and, arrived on scene during theafternoon of 31 August.

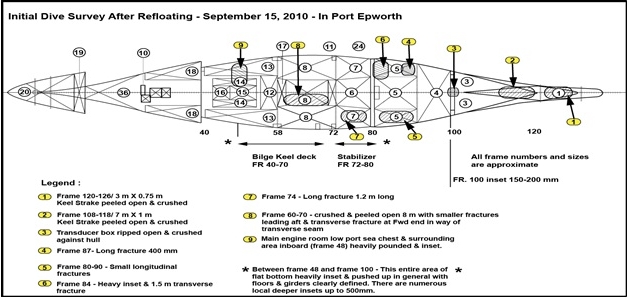

Salvage operation

On 01 September 2010, a dive team and a salvage company, engaged by the ship management company to refloat the Clipper Adventurer,arrived on site. The dive team discovered that the hull had sustained extensive damage from the forepeak to aft of amidships and that 13 double–bottom tanks and compartments including 4 full diesel oil tanks were holed, as opposed to the 7 originally reported by the crew.

The damaged tanks were double–bottom ballast water and fuel tanks. The contents of those containing fuel oil were transferred to other tanks. Given the density of salt water and the pressure of the ingress, the fuel oil floated over the water within the tank and as a result there was minor pollution. As a precaution, the crew deployed absorbent oil booms around the vessel to contain any pollution.

There was a deflection of the hull bottom in way of the boiler and machinery space, with vertical deflections of 1 to 5 cm in way of the boilers (Appendix C). As a result, the salvors declined to use the main engines during the refloating operation and Transport Canada (TC) and Lloyds Registry (LR) (the vessel's classification society), subsequently barred their use during the tow to Cambridge Bay and Nuuk, Greenland. A salvage planning meeting was held on board with all concerned parties including representatives of the owner, insurer, LR, Canadian Coast Guard, TC, flag state, and the vessel's crew.

Between 03 and 04 September, the salvage company engaged the AHTS Alex Gordon Footnote 15 and the tug Point Barrow, which had arrived on scene. TC requested stability calculations for the vessel's condition before allowing the initial salvage attempt. On 06 September, with the wind north–westerly at 40–45 knots, gusting 49 knots, with approximately 2 to 3 m seas, the vessel began rolling heavily, pitching, and pounding on the sea floor. This expedited the need for an initial attempt to tow the vessel off using the Alex Gordon. However, this attempt was unsuccessful and the vessel sustained further damage from boulders on the seabed (Appendix C).

On 08 September, the tug Nunakput was engaged by the salvage company and arrived at 1615 on 10 September. On 11 September, 2 more salvage attempts were made using roller bags and 3 tugs,Footnote 16 but these were also unsuccessful. Non–essential personnel were then transferred to the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier.

Between the 11 and 14 September, the vessel sustained further damage due to the prevailing adverse weather conditions. On 13 September the salvage company engaged a fourth tug, the Kooktook. On 14 September at 0900, with weather conditions again deteriorating, another attempt was made using the tugs Nunakput, Kooktook, Point Barrow and Alex Gordon. At 1340, the vessel broke free from the bottom and accelerated rapidly off the shoal.

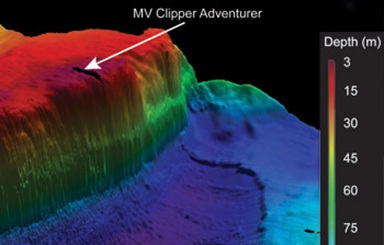

The salvage plan required hydrographic surveying of the shoal area and the route to Port Epworth and then as needed to Cambridge Bay. This was performed by Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS) personnel on board the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier.

On 14 September at 1904, the Clipper Adventurer anchored safely at Port Epworth. Winds continued to build throughout the evening to 50 knots, with gusts to 58 knots recorded in the wheelhouse despite being inside the protected anchorage of Port Epworth. Winds likely exceeded 60 knots at the grounding site. Throughout the night, the crew continued to monitor machinery spaces. No water ingress was reported.

On 17 September, the Clipper Adventurer was towed and escorted to Cambridge Bay, arriving on 18 September for additional inspections by the Classification Society and temporary repairs. The vessel departed Cambridge Bay on 25 September, arriving in Pond Inlet on 28 September for an escort handover to Canadian tug Ocean Delta. The Clipper Adventurer departed Pond Inlet with tug Ocean Delta on 07 October and arrived in Nuuk, Greenland on 12 October. Additional temporary repairs were completed in Greenland, allowing the vessel to transit to Iceland and finally Gdansk, Poland where permanent repairs were completed, including replacement of the forward looking sonar.

Environmental conditions

At the time of the occurrence, visibility was clear, the wind was north at 4 knots, the seas were calm and the outlook was good. The tide was at 0.4 m, its highest, and the water was clear. Sunset occurred at 2137.

Personnel certification and experience

The master, officers and crew all held certificates of competency valid for the vessel and voyage being undertaken.

The master had at least 35 years of polar experience of which 15 seasons had been spent in the Canadian Arctic. He had worked for the ship management company of the Clipper Adventurer for several years. He held a valid Unlimited Master Mariner certificate issued in 1979 in Sweden with a STCWFootnote 17 continued proficiency certificate valid until November 2010. This was the master's first voyage to Port Epworth, although he had been in the Coronation Gulf the previous year.

The chief officer had navigation experience in ice and in remote areas since 2003, with 4 seasons experience in the Canadian Arctic, and on other cruises with this master for 3 years. He held a valid Chief Officer Unlimited certificate issued in the Republic of Argentina and a Bahamian STCW endorsement as Master 1600 GRT or less.

Vessel certification

The vessel was designed and constructed for unrestricted international voyages and was classed 100 A1 Ice Class 1A Passenger Ship by Lloyd's Register. The vessel was crewed, equipped and certified in accordance with existing regulations and held a valid Safety Management CertificateFootnote 18 as required by the International Management Code for the Safe Operation of Ships and for Pollution Prevention (ISM Code). The Document of Compliance (DOC) was issued by Bureau Veritas on behalf of the Bahamas Authority on 20 November 2007 and was valid until 4 April 2012.

Canadian hydrographic service

The Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS) is a branch of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Its mission is to survey and chart Canada's oceans, lakes and rivers to ensure their safe, sustainable and navigable use, and to produce accurate publications including charts for the purpose of navigational safety. CHS publishes and maintains 946 nautical charts in paper and electronic format and over 100 companion publications. Each year it receives orders from 800 chart dealers worldwide and distributes nearly 300 000 nautical charts, tide tables and other nautical publications.

CHS Central and Arctic is responsible for conducting surveys in the Arctic. According to CHS, less than 10% of the Canadian Arctic is surveyed to modern standards, and many charts include information that was obtained more than 50 years ago ago using less reliable technologies than are available today. The routes commonly used are those that have been surveyed more extensively.

Discovery of the shoal

CHS conducts surveys to collect high–resolution data on the depth, shape, and structure of Canada's oceans, lakes, and rivers for the purpose of producing and updating charts and other navigational publications. When survey work is completed, the data is combined with shoreline and other navigation and topographical data for integration into a navigational chart.Footnote 19 CHS accepts outside sources of data to issue a chart modification if they consider the information to be sufficiently accurate and if it will serve to improve safety for mariners, in accordance with International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), SOLAS Chapter VFootnote 20 and CHS standards and processes.

The shoal on which the Clipper Adventurer grounded had been previously discovered on 13 September 2007 by the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier while conducting scientific research. The CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier reported the shoal to MCTS Iqaluit, who then broadcast a NOTSHIPFootnote 22 for CHS Chart No. 7777 indicating that, "a shoal was discovered between the Lawson Islands and the Home Islands in the Southern Coronation Gulf in position 67° 58.25′ N, 112° 40.39′ W. Charted depth in area 29 m. Least depth found 3.3 m. Isolated rock. Refer to NAD 83 datum." It was still in effect at the time of the grounding.

When the CCG Sir Wilfrid Laurier's crew first discovered the shoal in 2007 they were aware of the risks of crossing an island archipelago on a single line of soundings. They were transiting the area from the north at reduced speed. The bridge team was monitoring the depth sounder and lookouts scanning ahead for discoloration of the water indicative of shallower water.

On 14 September 2007, CHS Central and Arctic regional office received the information about the shoal discovered by the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier. It first established that there was a NOTSHIP that had been issued. Then, based on the preliminary information received, it determined the location would require more extensive surveying prior to issuing a permanent chart correction. In late 2007, there was an exchange of information between the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier and CHS Central and Arctic regarding the reported shoal. CHS Central and Arctic determined that the depth surveys conducted by the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier were not up to CHS standards. CHS standards are based on those of the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO). In accordance with IHO Regulation B–611.9 ,Footnote 23 permanent chart updates should not be made based on a single vessel report, with the exception of instances where:

- they originate from recognized survey vessels, research ships or other vessels/masters known to be reliable;

- they are reports of shoal depths, preferably accompanied by supporting evidence, e.g., an unambiguous echo–sounder trace, for areas where it is unlikely that corroboration can be obtained;Footnote 24

- they are the sole source of information in a remote area;

- they are of particular significance to navigation; or

- the location is in an area where the level of information flow and lines of communication are poor.

Notwithstanding the above, CHS Central and Arctic requires validated data with systematic coverage and a sufficient level of confidence before permanently modifying a chart. For example, it requires 3 types of hydrographic soundings in order to convey an accurate depiction of a hazard on charts: representational (periphery), significant (depths leading to peaks) and critical (peaks). In the summer of 2008, a CHS team of hydrographers on board the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier evaluated the accuracy of the data collected the previous year and confirmed that it was not sufficient to produce a chart correction according to CHS Central and Arctic practice.

On 4 September 2008, the passenger vessel Akademik Ioffe transited south into Port Epworth along the same line of soundings as the Clipper Adventurer was to later follow. The vessel's logbook recorded a depth of 16 m when passing near the 29 m sounding on the CHS chart No. 7777 in proximity to the shoal at 67° 58′. 4 N, 112° 40.0′ W. The vessel was not aware of NOTSHIP A102/07. At that time, the NOTSHIP was no longer being broadcast by radio but was available by other means (see list below).

CHS Central and Arctic has a prioritized list of areas to be surveyed. While CHS does not have dedicated vessels for surveys, CHS Central and Arctic typically plans to have 1 or 2 teams conducting surveys in the Arctic for several weeks during the summer navigation season and takes advantage of situations where CCG vessel routes and activities coincide with planned survey site locations on an opportunity basis.

In 2009, CHS had planned to survey the shoal based on their prioritized list. However, there was no opportunity at that time to survey the shoal using CCG vessels. Subsequent to the grounding of the Clipper Adventurer, a team of CHS hydrographers on board the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier completed a survey of the area. On 8 October 2010, CHS chart No. 7777 was corrected by a permanent indication of the shoal and a NOTMAR was issued.

Notices to shipping and notices to mariners

Canada uses the term "Notice to Shipping (NOTSHIP)"

to warn mariners about local navigation hazards. This term is not used outside of Canada, whereas the terms Local Warning and Navigational Warning are more widely used and recognized by foreign crews. For example, Canadian radio broadcasts use the term "Notice to Shipping," which is referred to in some other publications that the vessel is required have on board, such as the RAMN and the Sailing Directions. Before the 2011 Arctic season, there remained 5 active written NOTSHIPs issued since June 2006 referring to navigational hazards in the Arctic (i.e., shoal, rocks, and an islet). Two of these 5 sites have been surveyed. However, CHS is awaiting tidal corrections to release the NOTMARs for these 2 sites. For the remaining sites, CHS have not issued permanent chart corrections. NOTSHIPs are issued by the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) MTCS stations and remain active until a NOTMAR is issued or until the information is no longer necessary to mariners. In the Canadian Arctic, NOTSHIP A102/07 was available

- by radio broadcast according to the schedule advertised in the Radio Aids to Marine Navigation (RAMN) for a period of 14 days in the Arctic (which includes the CCG website link), twice daily during broadcast by MCTS;

- through NAVTEX within the 250 to 300 nautical miles (nm) range (Narrow Band Direct Printing Marine Telex) for 14 days after the shoal was discovered in 2007 (A102/07);

- through HF Narrow Band Direct Printing (HF–NBDP) (8 MHz) receivers that can be used where service is available as an alternative to Inmarsat–C. The range of this broadcast is 800 miles, dependent upon radio propagation. In this instance, Notice to Shipping A102/07 was broadcast as a NAVAREA XVIII message (NAVAREA 5/10)Footnote 25.

- through online access to CCG website;Footnote 26

- through a weekly list that is faxed or emailed to subscribers;

- by request to MCTS; and,

- effective since 01 July 2010, by SafetyNET Broadcast twice daily through Inmarsat–C for NAVAREA/METAREAFootnote 27 warnings for a period of 6 weeks as per IMO standards. In this instance the broadcast of NAVAREA XVIII 5/10 was effective on 01 July 2010 for a period of 50.5 days ending on 20 August 2010.

In 2010, the CCG assumed the responsibility of NAVAREA coordination for NAVAREAs XVII and XVIII as part of the World–Wide Navigational Warning Service (WWNWS). The service was in "Initial Operational Condition" (IOC) effective July 1, 2010. During the IOC period, the Canadian Coast Guard did not guarantee service availability as this service was provided on a test basis. The service entered "Full Operational Condition" (FOC) in June 2011.

Transmissions were sent twice a day for each NAVAREA/METAREA XVII and XVIII warnings by Inmarsat–C SafetyNET. Due to satellite coverage limitations above 76 ° N latitude, these messages were also broadcasted on a test basis by HF–NBDP. At the start of IOC, all previously issued but still active Notices to Shipping (NOTSHIPs) that met the criteria for NAVAREA warnings were broadcast via Inmarsat–C SafetyNet and HF NBDP NAVAREA XVIII warning 5/10. This HF NBDP broadcast (8416.5 MHz) was included in RAMN 2010.

CHS issues chart and publication corrections in the form of NOTMAR. These can be permanent, temporary or preliminary. NOTMAR are issued when hazards are confirmed, but may also be issued when surveys have not been completed to CHS standards. In such cases, NOTMAR take one of the following forms:

- Position Approximate (PA)

- Position Doubtful (PD)

- Existence Doubtful (ED)

- Sounding Doubtful (SD).

PAs can be used to indicate that the position of a shoal, wreck or navigational hazard has not been determined or does not remain fixed. PDs are used to indicate that a wreck, a shoal or other navigational hazard has been reported in various positions but not confirmed in any of them. In 1960, CHS utilized PDs on chart No. 7777 to indicate reported shoals that were not confirmed (Appendix D). These symbols are part of IHO standards.

Over time, it became CHS Central and Arctic's systematic practice to avoid PA or PD chart corrections due to possible inaccuracies in the information provided to them. The rationale is that should a PA or PD be placed on a chart in an incorrect location based on incomplete information, mariners may be misled or could contact another unreported hazard. Consequently, CHS Central and Arctic relies on the use of NOTSHIPs to warn mariners rather than issuing PA and PD chart corrections for reported navigational hazards that have not been surveyed to CHS standards.

Northern Canada vessel traffic services

NORDREG is the Canadian Arctic marine traffic system created pursuant to the Northern Canada Vessel Traffic Services Zone Regulations. The system is designed to ensure that the most effective services are available to accommodate current and future levels of marine traffic. Participation is mandatory for all vessels of over 300 gross tonnage. NORDREG is operated by CCG MCTS personnel from the Iqaluit, Nunavut MCTS Centre. The MCTS Centres forward messages and are in continuous contact with NORDREG. The NORDREG system keeps track of all traffic north of 60° N, as well as within Ungava Bay and the southern part of Hudson Bay, providing recommended routes and general ice conditions. Vessels entering the NORDREG system must provide a sailing plan report that includes the vessel's intended route. On 18 August 2010, NORDREG received the sailing plan report from the Clipper Adventurer, which included a stop at Port Epworth. When receiving these reports and providing routing advice, NORDREG does not issue to vessels the written NOTSHIPs applicable to their routes, which is consistent with existing CCG levels of serviceFootnote 28 for all MCTS Centres and NORDREG procedures for issuing NOTSHIPs. However, NORDREG does advise mariners at the end of each broadcast, twice daily, that all active NOTSHIPs are available via the Internet.

Chart dealers and chart No. 7777

CHS–approved third–party chart dealers stock and sell charts and related publications. Some dealers provide customers with information on how to maintain their charts current to recent NOTMAR. Others have created chart correction tools such as tracings of NOTMAR and can be hired to perform audits of chart portfolios. The Clipper Adventurer's management company used a chart correction service to ensure that its charts were up–to–date. However, this did not include the provision of NOTSHIPs. In 2009, the Clipper Adventurer purchased CHS chart No. 7777. This chart was stamped as being corrected with NOTMARs up to 25 July 2008. The last NOTMAR issued was dated 04 June 2004 and had been applied to chart No. 7777.

The chart's source classification diagram indicated that the area around Port Epworth contained soundings from sources other than CHS and without specific dates for each one. The distance between the spot soundings on the single–line varied between 0.4 nm to 0.7 nm. There were no bathymetric contours indicated on the chart in this area. The intended route between Port Epworth and Kugluktuk was along a single line of soundings with uncharted waters all around. The shoal was located on the vessel's intended route. The bridge team used the vessel's Electronic Chart System (ECS) to monitor the progress of the vessel as displayed on raster navigation chart (RNC) CHS No. 7777.

Safety management systems

International safety management code

The International Management Code for the Safe Operation of Ships and Prevention of Pollution (ISM) has the overall aim of providing an international standard for the safe management and operation of ships and for pollution prevention. Effective safety management requires large and small organizations to be cognizant of the risks involved in their operations, to competently manage those risks and to be committed to operating safely. In order to accomplish this, a vessel operator must evaluate existing and potential risks, establish safety policies and related procedures to mitigate those identified risks and provide a means to continuously gauge performance through audits, so as to improve organizational safety where necessary. The resulting documented, systematic approach helps ensure that individuals at all levels of an organization have the knowledge and the tools to effectively manage risk, as well as the necessary information to make sound decisions in any operating condition. This includes both routine and emergency operations.

Companies operating passenger vessels such as the Clipper Adventurer have been required to comply with the provisions of the ISM code since July 1998. The company that managed the Clipper Adventurer charters and manages passenger vessels worldwide and has had several ships sailing the Arctic on previous voyages. The company has dedicated shore teams responsible for managing each ship with respect to maintenance, staffing, budgeting and purchasing. The shore team reviews each proposed itinerary to verify that cruises can be undertaken. The itinerary is then passed on to the vessel's bridge team to complete the requisite passage plan.Footnote 29

One of the key functions of a safety management system (SMS) is to manage risk proactively. This includes the identification, assessment and analysis of risk, and the establishment of safeguards against all identified risks. Prior to the grounding, the management company QSEP did not identify all of the risks associated with navigation in poorly charted areas or put in place specific procedures or guidelines for operating in the Arctic, including ensuring that the voyage plan was revised in conjunction with the management company; that the forward looking sonar unit was operable; that zodiacs with portable echo–sounders were used when necessary; that vessels transited at lower speed when operating in poorly charted areas; and that local navigation warnings were obtained.

Internal audit

The objectives of the ship management company's internal audit program are to verify the effectiveness of the QSEMS and the compliance of the officers and crew.

Internal audits are conducted by ship management annually. In 2009, the company's auditor conducted an internal audit using a document checklist based on the company's Audit Program. Items verified included the Voyage Planning form, Deck Logbook entries and chart corrections. The 2010 audit for Clipper Adventurer was scheduled for September or October. The audit was postponed following the grounding and took place when the vessel arrived in Poland for repairs.

Voyage data recorder

Various modes of transportation have used data recorders to assist accident investigators. The aviation industry has enjoyed the benefits of flight data and cockpit voice recorders for many years, but experience with voyage data recorders (VDRs) in the maritime industry is relatively new. In addition to bridge audio, a VDR is capable of recording such parameters as time; vessel heading and speed; gyrocompass; alarms; VHF radiotelephone communications; radar; the echo–sounder, status of hull openings; wind speed and direction; and rudder/engine orders and responses.

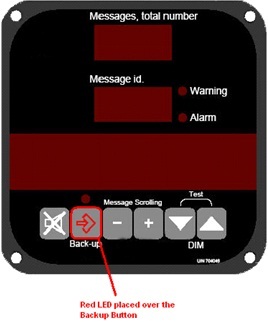

Following the grounding, the bridge team was required by the company Quality, Safety, and Environmental Protection (QSEP) program to activate the "backup memory button" from the VDR System Control and Alarm Unit (SCU) located on the bridge (Figure 4). Several requests to backup the data were made by the company following requests by the TSB. The vessel's flag state (Bahamas) also requires that VDR data be preserved in the case of "very serious and serious casualties."Footnote 30 The bridge team had confirmed that 12 hours of data had been saved.

On 03 September 2010, the TSB investigation team attempted to download data from the VDR but no data had been saved. Since the backup procedures had not been followed by the bridge team, the VDR had continued to record data following the grounding, overwriting the data recorded at the time of the grounding.

Analysis

Upon departure from Port Epworth, the Clipper Adventurer followed the planned course along a single line of soundings at 13.9 knots. The vessel ran aground on a previously reported shoal not marked on the chart in use. This analysis will consider route selection, navigation practices in Arctic waters, the availability of navigation information, and the management of safety.

Route selection

When completing the Voyage Planning Form, 2 routes from Port Epworth to Kuglutuk were considered (Figure 1). One route (B) would take the vessel south of the Lawford Islands along a single line of soundings and with difficult navigation at its western end. The other route (A), chosen in this occurrence, also followed a single line of soundings.

An alternative route (C) was available using the vessel's reciprocal track northeast back to the main east/west surveyed channel. It was not chosen by the bridge team due to the extra distance of 200 miles. The vessel was scheduled to arrive in Kugluktuk at 0800 on 28 August 2010. This arrival time could have been achieved by either the chosen route (A), 90 nm to Kugluktuk at a speed of 6 knots, or by the longer route (C), 200 nm at a speed of 13 knots. Either route would have allowed the vessel to reach Kugluktuk on schedule.

The Clipper Adventurer ran aground on a previously reported but uncharted shoal after the bridge team chose to navigate a route on an inadequately surveyed single line of soundings.

Navigation in inadequately surveyed areas

A bridge management team is expected to navigate with particular caution where navigation may be difficult or hazardous. The Clipper Adventurer's bridge team was following a single line of soundings made in a 1965 survey, using less reliable technology than that available today, and was not aware of the NOTSHIP regarding the shoal.

Although the absence of bathymetric contour lines on the chart indicated an incomplete hydrographic survey of the area, the master of the Clipper Adventurer was confident in his choice of route and speed, having navigated in polar waters for decades using single lines of soundings without incident. Furthermore, the chart indicated no navigational hazards along the chosen route, the chart dealer had provided all the latest chart corrections, and the existence of a line of soundings indicated that at least one other vessel had successfully transited that route.

In order to reach Kugluktuk on schedule, the Clipper Adventurer needed to proceed at a speed of 6 knots. However, the Clipper Adventurer was proceeding at full sea speed of 13.9 knots, which significantly exceeded the speed required to meet the scheduled arrival. Additionally, the vessel was not operating with a functional forward looking sonar, nor were one or more of the vessel's inflatables, equipped with portable echo–sounders, dispatched to precede the vessel.

With the forward looking sonar unserviceable, the vessel relied on the echo–sounder to monitor the accuracy of the charted soundings. However, the echo–sounder provided the depth beneath the vessel and not the depth ahead. As a consequence, the vessel struck the shoal at full sea speed, damaging the hull and the propulsion machinery.

Forward looking sonar – status

The unserviceable condition of the forward looking sonar deprived the bridge team of an additional source of valuable information. Forward looking sonars are designed to provide safety critical information regarding underwater obstructions ahead of ships, and provide automatic navigation alerts to bridge teams. As time is critical when an obstruction is detected, it is important to take into account the maximum range of the forward looking sonar when determining the appropriate speed. Based on performance specifications for the unit fitted on the Clipper Adventurer, the crew could have been warned approximately 48 seconds in advance given the speed of 13.9 knots. At a speed of 6 knots, the crew could have been warned approximately 2 minutes in advance. Without the valuable information available from a functional forward looking sonar, and given the hazards inherent in navigating inadequately surveyed areas, the vessel's speed of 13.9 knots was probably not prudent.

Canadian hydrographic service chart corrections

Once a chart has been published, it is subject to amendments and corrections as new information becomes available. Before applying such permanent amendments or corrections, it is CHS Central and Arctic regional practice to conduct a complete hydrographic survey. In this instance, the initial data provided to CHS Central and Arctic by the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier did not meet the CHS Central and Arctic regional practice for a permanent chart modification. However, as the information had come from a reliable source, it did meet the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) criteria for a chart modification in a remote area using IHO–recognized NOTMAR Position Approximate (PA) or Position Doubtful (PD) symbols.

The use of the symbols PA or PD on a chart provides a visual warning of the presence of a possible hazard and seafarers would be expected to navigate with additional caution around this hazard. However, CHS Central and Arctic tries to avoid issuing PAs or PDs on Arctic charts because of the risk that incorrect or incomplete information in poorly surveyed areas could mislead mariners as to the true location of the hazard, or onto another unreported hazard. A similar risk exists with a NOTSHIP as it provides the same information. In addition, a NOTSHIP does not specify that the position of the hazard is approximate or doubtful. The use of the symbols PA or PD on a chart provides a visual warning of the presence of hazards, which are intended to advise mariners to navigate with caution.

Given the data provided by the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier regarding the existence of the shoal, CHS Central and Arctic had a mechanism in place to issue a PA chart correction identifying the reported shoal on chart No. 7777. However, since it was not its common practice to do so, no chart correction was issued, depriving the bridge team on the Clipper Adventurer of one possible source of critical information.

The practice of CHS Central and Arctic not to issue PA and PD chart corrections increases the risk that mariners may be unaware of known hazards should they not obtain applicable NOTSHIPs.

Retrieval of notices to shipping

The completion of a comprehensive voyage plan prompts mariners to source information important to safe navigation. This includes ensuring that the courses have been laid out on the appropriate charts, that the latest corrections have been applied to these charts, that all the appropriate nautical publications have been consulted, and that the relevant navigational warnings have been obtained. In this occurrence, the Clipper Adventurer's bridge team laid out the courses and completed the company's Voyage Planning Form. Their voyage plan did not consider local navigational warnings known in Canada as Notices to Shipping (NOTSHIP).

Although the bridge team possessed up–to–date charts and publications from the dealer, these did not include local navigational warnings. In Canada, these can be obtained through numerous methods including Inmarsat–C SafetyNet NAVAREA broadcasts, HF NBDP 8146 MHz broadcasts, the CCG website and by contacting an MCTS Centre. Once the Inmarsat SafetyNet NAVAREA XVIII warning 5/10 ended on 20 August 2010, the information regarding the shoal was available via HF NBDP, the CCG website or by contacting a MCTS Centre. Vessels operating in the Canadian Arctic may have limited access to the Internet due to an unreliable connection because of satellite geometry. This may limit the mariners' ability to access NOTSHIPs or other valuable navigation information.

The investigation could not determine why the bridge team were not aware of NOTSHIPs, nor why they did not seek them out from the readily available sources while planning and conducting the voyage. The methods for obtaining active written NOTSHIPs or NAVAREA broadcasts are identified in the Radio Aids to Marine Navigation (RAMN). Furthermore, the HF NBDP (8416.5 MHz) SafetyNet broadcast was published in RAMN 2010. The area in which the vessel was operating, NAVAREA XVII–XVIII, was also within range of Inmarsat–C SafetyNET broadcasts and HF NBDP was available as an alternate to Inmarsat–C. Although the vessel was fitted with all of the necessary equipment to receive broadcasts of messages pertaining to navigational warnings for the area, the bridge team was not aware of NOTSHIP A102/07 and NAVAREA XVIII warning 5/10.

NORDREG vessel traffic services in the Arctic

Knowledge of hazards to navigation through reporting mechanisms is crucial to ensure safe navigation. Through the mandatory NORDREG vessel reporting system, the CCG is the initial point of contact for all vessels transiting the Arctic. It has been noted that 5 NOTSHIPsFootnote 31 issued since June 2006 that refer to navigational hazards (i.e., shoal, rocks, and an islet) remained active for Arctic waters at the start of the 2011 season, but are no longer broadcast through MCTS. These 5 written NOTSHIPs can now only be accessed through the CCG website or by specific request to MCTS.

Obtaining NOTSHIPs through the CCG website can be problematic due to unreliable Internet access north of 60 ° Latitude. As a result, access to NOTSHIPs may be limited to HF–NBDP and a specific request made to MCTS. The issuing of NOTSHIPs only through these 2 means is a passive method reliant on both a mariner's awareness of how to obtain the information and the vessel being equipped with the appropriate technology to do so. Such an approach may be problematic for vessels entering the Canadian Arctic for the first time and for the bridge teams of foreign flag vessels who may be unfamiliar with Canadian use of the term NOTSHIP.

Furthermore, the NORDREG vessel reporting system requires that vessels must submit a detailed sailing plan report prior to arrival in Canadian Arctic waters. However, when receiving sailing plan reports and providing routing advice to vessels, NORDREG does not proactively advise vessels about active NOTSHIPs for the areas that they will be transiting.

Safety management

The International Management Code for the Safe Operation of Ships and For Pollution Prevention (ISM Code) has the overall aim of providing an international standard for the safe management and operation of ships engaged in international voyages and for pollution prevention. One of the main objectives set out by the ISM Code is for companies to "establish safeguards against all identified risks."

Voyage planning

Although the management company's Quality, Safety, and Environmental Management System (QSEMS) did not contain specific procedures for operating in the Arctic, it did require key documents to be on board the vessel which identified specific measures to follow when operating in remote and poorly surveyed areas. In addition to the Sailing Directions – Arctic Canada Vol 1, one such document referenced was Transport Canada's (TC) Guidelines for the Operation of Passenger Vessels in Canadian Arctic Waters.Footnote 32This TC document cautions that waters north of 60° are not well–surveyed and soundings in many areas are based on reconnaissance surveys and are not up to international standards. The document also contains a reference to NOTSHIPs, indicating that they are broadcast by MCTS.

Once the seasonal cruise program had been determined for the Clipper Adventurer, the management company relied on the experience and competency of the bridge team, expecting it to follow the procedures established by the company's QSEMS. Before commencing the voyage, the Clipper Adventurer's bridge team laid out the courses and completed the company's Voyage Planning Form. The vessel was equipped with up–to–date charts, publications were on board including the TC guidelines, and the vessel was fitted with all necessary equipment to receive the broadcast NOTSHIPs. However, the bridge team was not aware of, nor did they seek out NOTSHIPs while planning and conducting the voyage.

This was the Clipper Adventurer's second season in the Canadian Arctic. Throughout the voyage planning process, the master and ship management company were aware that the forward looking sonar was not serviceable. However, the vessel's management company had not detected irregularities with voyage planning through its ongoing management of the QSEMS. The voyage planning practice on board the Clipper Adventurer did not fully comply with the ship management company's Quality, Safety, and Environmental Protection (QSEP) program, in that local warnings (NOTSHIPs) were not obtained.

Procedures for Arctic voyages

One of the key functions of an SMS is to proactively manage risk. This includes the identification, assessment, analysis, and the establishment of safeguards against all identified risks. At the time of the occurrence, the ship management QSEMS operations manual did not contain specific provisions to ensure that safety critical equipment, such as the forward looking sonar was serviceable. In addition, procedures and precautionary measures, such as the use of forward looking sonar as a means of determining a prudent speed in inadequately charted areas, were also not identified. Providing specific procedures for these conditions in the company's operations and safety manual would have provided guidance to the bridge team, and should have advised them to take precautionary measures when transiting in Arctic waters. The voyage planning practice on board the Clipper Adventurer did not fully comply with the ship management company's Quality, Safety, and Environmental Protection (QSEP) program in that the bridge team did not use the Bridge Procedures Guide for a passage plan appraisal. As well, the ship management company's SMS did not provide the vessel's staff with procedural safeguards to mitigate the well–known risks associated with operation in the Arctic such as providing a serviceable forward looking sonar and ensuring that local navigational warnings were obtained.

Refloating attempts

Before attempting to refloat a grounded vessel, the condition of the vessel must be known, all risks assessed, and appropriate measures put in place to mitigate those risks. It is the master's responsibility to weigh the risks of remaining aground or taking prompt action to refloat the vessel and, in some instances, the resulting decision must be made on the basis of incomplete information.

At the time of the grounding, no salvage vessels were in the area and the CCGS Amundsen was approximately 36 hours away from the site. The vessel was firmly aground and severely damaged, while the weather forecast did not indicate that the vessel would be subject to further risk if it remained aground. Upon deciding to refloat the vessel after the grounding, the master did not have sufficient damage stability information to assess whether or not the vessel would be stable once off the shoal. The master's knowledge of damage was limited to which tanks were flooding. The actual condition of the hull, including the hull structure under the machinery space, which had been damaged and significantly deflected, was unknown. Notwithstanding, the master reported to MCTS Iqaluit that he had propulsion, and the main engines were run during the first attempts to refloat the vessel. During these attempts, the passengers shipboard routine continued as normal and, though they were kept informed, they were not re–mustered.

Following the occurrence, a damage stability assessment was conducted by the TSB that determined that the vessel did have sufficient stability had it been refloated before a decision was made to request a salvage operation. Even though there were no adverse consequences in this instance, without readily available SAR resources, and a complete formal assessment of the vessel's seaworthiness, including damage stability, residual hull strength and machinery condition prior to a refloat attempt, such decisions may place a vessel, passengers and crew at risk.

Voyage data recorder

The purpose of a Voyage Data Recorder (VDR) is to create and maintain a secure, retrievable record of information indicating the position, movement, physical status, and command and control of a vessel for the period covering the most recent 12 hours of operation. Objective data is indispensible to accident investigators seeking to understand the sequence of events and identify operational problems and human factors issues.

The bridge team did not capture VDR data as required by the company's SMS even though they were advised to do so by the designated person ashore following a request by the TSB. The backup procedure was not followed by the bridge team and the VDR continued to record data after the grounding, overwriting the data recorded at the time of the grounding. When bridge recordings are not available to an investigation, this may preclude the identification and communication of safety deficiencies to advance transportation safety.

Findings

Findings as to causes and contributing factors

- The Clipper Adventurer ran aground on an uncharted shoal after the bridge team chose to navigate a route on an inadequately surveyed single line of soundings.

- Despite having a non–functional forward looking sonar or using any other means to assess the water depths ahead of the vessel, the Clipper Adventurer was proceeding at full sea speed (13.9 knots).

- The shoal had been previously identified and reported in a Notice to Shipping (NOTSHIP). However, the bridge team was unaware of and did not actively access local NOTSHIPs, nor did NORDREG specifically advise them of the NOTSHIPs applicable to the vessel's area of navigation.

- Canadian Hydrographic Service (CHS) Central and Arctic did not issue a chart correction, depriving the bridge team of one source of critical information regarding the existence of a shoal on their planned route.

- The voyage planning practice on board the Clipper Adventurer did not fully comply with the ship management company's Quality, Safety, and Environmental Protection (QSEP) program by not using the Bridge Procedures Guide for a passage plan appraisal, which resulted in local warnings (NOTSHIPs) not being obtained.

- The ship management company's SMS did not provide the vessel's staff with safeguards to mitigate well–known risks, including revision of the voyage plan in conjunction with the management company; assurance that the forward looking sonar unit was operable; use of the zodiacs with portable echo–sounders when necessary; assurance that the vessel transited at lower speed when operating in poorly charted areas; and acquisition of NOTSHIPs local navigation warnings.

Findings as to risk

- The practice of CHS Central and Arctic not to issue and apply chart corrections using Position Approximate and Position Doubtful symbols increases the risk that mariners will not be aware of known hazards when they do not obtain the applicable NOTSHIPs.

- When NOTSHIPs are no longer broadcast, vessels operating in Canadian Arctic waters can only obtain the information on written NOTSHIPs by specific requests to MCTS or by accessing the CCG website, in areas with unreliable Internet connectivity, which may limit the mariners awareness of known hazards.

- When receiving sailing plan reports and providing routing advice to vessels, NORDREG does not proactively advise vessels about active NOTSHIPs for the areas that they will be transiting which may place vessels at increased risk if they have not obtained the information by other means.

- Unless there is a complete assessment of the seaworthiness of a vessel prior to a refloating attempt, a vessel, its passengers and crew may be placed at risk.

- When bridge recordings are not available to an investigation, this may preclude the identification and communication of safety deficiencies to advance transportation safety.

Other findings

- The term Notice to Shipping is not used outside Canada, whereas the terms Local Warning and Navigational Warning are more widely used and recognized by foreign crews.

- On 4 September 2008, the passenger vessel Akademik Ioffe transited southbound to Port Epworth following the same line of soundings. The bridge team was also not aware of NOTSHIP A102/07.

Safety action

Identifying navigational hazards in the Arctic

I. Communication of Notices to Shipping in the Arctic

On 16 June 2011, the TSB issued Marine Safety Advisory No. 02/11 to the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) advising them of the importance of ensuring that vessels transiting the Arctic are provided with Notices to Shipping relevant to the routes they are intending to follow.

On 03 April 2012, the TSB met with DFO as a follow–up to the MSA. The TSB reiterated its safety concern and requested an update on DFO's intentions regarding NORDREG policies.

During the meeting, the TSB expressed the following concerns. The Canadian Arctic Archipelago is very remote from available Search and Rescue (SAR) and pollution response resources. Consequently, accidents such as the grounding of the Clipper Adventurer can have far reaching impacts, including the possible damage or loss of vessels, injuries and loss of life, and damage to the fragile northern environment. The grounding of the Clipper Adventurer is not the first occurrence involving passenger vessels in the Arctic where NORDREG had not supplied information regarding this shoal directly to a vessel. On 04 September, 2008, the Russian passenger vessel Akademik Ioffe passed close by the same uncharted shoal, unaware of its existence.Footnote 33 Similar to the Clipper Adventurer, the crew of the vessel had not been proactively supplied with information regarding the existing NOTSHIP. In addition, it is reported that the Canadian tugs that came to the aid of the stranded Clipper Adventurer were also unaware of the shoal until they were informed by the CCGS Sir Wilfrid Laurier.

Until 1988, there were few passenger ships voyaging to the Arctic. In the years 1980–1987, there were only 4 Arctic passenger voyages conducted by one passenger vessel. However, in the past 7 years, there have been a total of 105 distinct voyages conducted by 7 different passenger vessels. During this time, there has been an average of 9 passenger vessels per year conducting a total of 15 voyages per year. With approximately 105 passengers per voyage, there are at least 1575 passengers in the Arctic every year.

Of the 118 vessels in the Canadian Arctic that conducted 284 voyages in 2011, there were 15 tankers and 7 passenger vessels. Tankers are considered to be of high risk because an accident could have severe environmental consequences. Passenger vessels are also considered high risk since, among other consequences; an emergency in the Arctic could leave passengers and crew stranded for an extended period of time in a harsh environment.

It is expected that with the continued melting of polar ice in the future, traffic will increase as vessels (particularly foreign flagged and crewed) increasingly use the Northwest Passage, and new and previously inaccessible areas open up for passenger ships to visit. Given the remoteness of the region, the navigational challenges of the Arctic, and the potential unfamiliarity of foreign crews with Arctic navigation, the Board is concerned that if up–to–date information about hazards to safe navigation does not reach vessels, passengers, crew and the environment are at increased risk.

DFO recently provided a written response to the TSB. Starting with the 2012 Arctic navigation season, the Canadian Coast Guard will utilize the mandatory NORDREG vessel reporting system to proactively provide all vessels with a list of NOTSHIPs that are applicable to Arctic waters north of 60 degrees.

When a vessel first reports to NORDREG, a summary listing of all Arctic NOTSHIPs will be appended to the NORDREG clearance message. The master of the vessel can use this summary listing to determine the details of the appropriate NOTSHIPs along his intended route from a variety of sources, such as via the Internet or the Iqaluit Marine Communications and Traffic Services centre, before entering NORDREG Vessel Traffic Service Zone.

II. Chart Corrections in the Arctic

On 16 June 2011, the TSB issued Marine Safety Information No. 05/11 to the Canadian Hydrographic Services (CHS) of the DFO informing them of 5 Arctic NOTSHIPs issued since June 2006 that refer to navigational hazards and that remain active.

In response, CHS indicated the following:

- NOTSHIP A07/06 – Eastern Arctic – Chart 7569 – 21 June 2006

CHS is aware of the approximate position of the island and has captured the information in its database. The position and elevation of the island will be accurately surveyed the next time CHS is able to get to the area.

- NOTSHIP A96/08 – Eastern Arctic – Chart 7212, 7220 – 6 September 2008

The charted depth and position of the drying rock has been confirmed. A Notice to Mariners (NOTMAR) will be completed once the tidal adjustment is calculated and applied.

- NOTSHIP A98/08 – Eastern Arctic – Chart 7212, 7220 – 6 September 2008

The charted depth and position of the shoal has been confirmed. A NOTMAR will be completed once the tidal adjustment is calculated and applied.

- NOTSHIP A128/08 – Eastern Arctic – Chart 5300, 7050 – 1 October 2008

The accuracy of the reported positions of the rocks could not be determined. The area will need to be surveyed before they can be charted or a NOTMAR issued.

- NOTSHIP A97/09 – Western Arctic – Franklin Strait – 18 September 2009

CHS is aware of the shoal and has captured the information in its database. It will be accurately surveyed the next time CHS is able to get to the area.

On 03 April 2012, the TSB met with DFO as a follow–up to the MSI. The TSB reiterated their safety concern and requested an update on DFO's intentions regarding CHS policies.

During the meeting, the TSB expressed the following concerns. The shoal had originally been discovered and reported in September 2007 by a CCG vessel with a recognized ability to survey in these waters. Although the bridge team possessed up–to–date charts, the charts did not indicate the existence of the shoal. Although this shoal had not yet been surveyed, International and Canadian hydrographic standards provide a process where reasonably reliable reports of hazards to navigation are incorporated through published chart corrections by NOTMAR prior to an official survey. These chart corrections include the designations Position Approximate (PA) and Position Doubtful (PD), which are internationally used and understood. CHS Central and Arctic did not follow these standards and practices of putting these designations on its charts.

DFO recently provided a written response to the TSB, indicating that in order to better respond to increasing demands for products and services, Canadian Hydrographic Services (CHS) is establishing a more rigorous national planning and prioritization process which will bring more consistency among the regions and conformity to the required levels of standards appropriate to Canadian traffic, geographical and weather conditions. In 2013, CHS will establish a procedure to update navigational charts north of 60 degrees when a hazard to navigation is discovered by a credible source, as per international protocols.

Given the importance of timely chart corrections, the Board expects that implementation of this procedure will result in updating navigational charts north of 60 degrees when a hazard to naviagation is discovered by a credible source, as per international protocols, as soon as possible thereafter. The Board will monitor progress on this important issue.

New edition of chart No. 7777

Since the occurrence, several NOTMARs, including NOTMAR LNM/D 08–OCT–2010 concerning the shoal in this occurrence, have been issued to update chart No. 7777. Further, newly acquired survey data will be incorporated by CHS into a new edition of chart No. 7777. As such, CHS will be issuing an electronic navigatinoal chart (ENC) in June 2012 and, subsequently, a paper chart will also be available to mariners.

Voyage planning for vessels in the Arctic

Transport Canada prepared a general notice on Voyage Planning for Vessels Intending to Navigate in Canada's Northern Waters. This notice was published in the monthly Notices to Mariners (Vol. 36, Monthly Edition No. 08) on 28 August 2011, and amends the 2011 Annual Notices to Mariners (Notice 7A). The purpose of the notice is to assist mariners, owners, and operators intending on navigating Canada's northern waters with preparing for, and executing, a safe voyage.

Flag state

The Bahamas Maritime Authority has conducted an investigation surrounding the grounding of the Clipper Adventurer. The report has not been released.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board's investigation into this occurrence. Consequently, the Board authorized the release of this report on . It was officially released on .