Main-track train derailment

Canadian National Railway Company

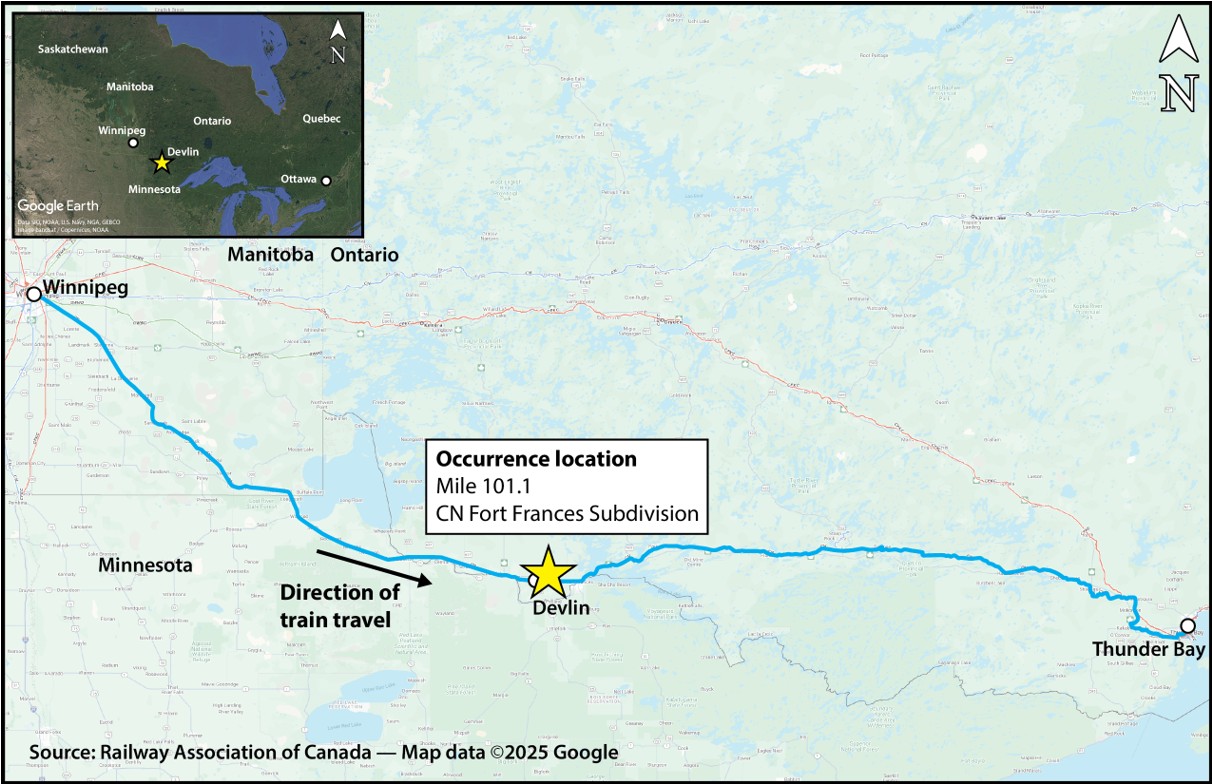

Freight train G89641-28

Mile 101.1 Fort Frances Subdivision

Near Devlin, Ontario

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

The occurrence

On 28 June 2025, Canadian National Railway Company (CN) unit grain train G89641-28 was proceeding eastward on the Fort Frances Subdivision, from Winnipeg, Manitoba, to Thunder Bay, Ontario.All locations are in the province of Ontario, unless otherwise indicated. The distributed power train was powered by 2 locomotives, 1 at the head end and 1 at the tail end. It was hauling 134 loaded cars, weighed 18 578 tons, and was 7853 feet long.

At about 1340 Central Daylight Time, while the train was travelling at 41 mph in a 0.9° right-hand curve, a train-initiated emergency air brake application occurred at Mile 101.1 near Devlin (Figure 1). After the train came to a stop, the crew conducted an inspection and found that 13 hopper cars near the tail end (positions 119 to 131) had derailed (Figure 2). Most of the derailed cars were extensively damaged and released their product. There were no injuries.

Weather information

At the time of the accident, the temperature was 28.6 °C and the skies were clear. The area had experienced sharp temperature variations during the week preceding the occurrence. From 20 to 28 June, the daytime temperature was over 21 °C, reaching a high of 28.6 °C on the day of the occurrence. The nighttime temperature varied from 19.9 °C on 22 June to 5.2 °C on 24 June.

Subdivision information

The Fort Frances Subdivision runs east-west between Atikokan (Mile 0.0) and Rainy River (Mile 143.6). Train movements on the subdivision are controlled by the centralized traffic control system, as authorized by the Canadian Rail Operating Rules, and are dispatched by a rail traffic controller located in Edmonton, Alberta.

Traffic on the subdivision consists of 15 trains per day on average. In 2024, the train traffic was 78.7 million gross ton-miles per mile on the section between Fort Frances (Mile 89.1) and Rainy River. The heavy tonnage traffic consists primarily of trains transporting loaded bulk products east toward Duluth, Minnesota, United States, or Thunder Bay. The westward traffic is typically much lighter, as it consists mostly of trains transporting empty cars.

Track information

The track is classified as Class 4 according to the Rules Respecting Track Safety, also known as the Track Safety Rules (TSR). The authorized speed for freight trains in the area where the train derailed was 50 mph. There were no slow orders in effect at the time of the occurrence.

The main line near Mile 101.1 is a single main track. A siding runs on the south side of the main track from Mile 99.4 to Mile 101.7. At Mile 101.46, the track crosses Ontario Highway 613.

In July 2025, the TSB examined the track in the area of the derailment. Signs of previous rail creepRail creep is the gradual longitudinal movement of the rail and is induced by variations in temperature (thermal stress), train traffic (predominantly unidirectional loaded traffic), or both. were observed in several locations. At Mile 101.8, the anchors had been repositioned by up to 4 inches (Figure 3) during repairs conducted after the derailment. The track in the adjacent siding showed signs of rail creep; in some cases, the anchors were displaced by up to 6 inches (Figure 4). All the anchor displacements on the main track were in the eastward direction, indicating that the rail creep was in the direction of the heavy tonnage traffic.

Rail creep is a sign of compressive stress in the rail. Excessive compressive forces can cause track buckling (lateral deformation of the track). Compressive stress can be proactively managed by reinforcing track securement (for instance by adjusting the position of the anchors closer to the ties or by replacing the anchors) or by destressing the rails.Rail destressing consists of cutting the rail and removing the anchors to release any built-up stress. Once the stress is released, any excess rail is removed or new rail is added if required. The rails are then welded back together and re-anchored.

Unless the underlying compressive stress is addressed, rail creep grows increasingly more pronounced over time. Rail creep is more detrimental when it is unidirectional, which occurs when there is a significant imbalance in the traffic tonnage in one direction as opposed to the other, as in the case of the Fort Frances Subdivision. Rail creep of 4 to 6 inches, as observed in the area where the train derailed, typically takes several months or even years to develop.

Track buckling

A track buckle is a lateral misalignment of the railsA. Kish and W. Mui, Track Buckling Research, John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center, Federal Railroad Administration, Office of Research and Development, United States (09 July 2003) at https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/11985 (last accessed 14 November 2025). that occurs when longitudinal compressive stresses build up in the rail and overcome the lateral resistance of the track structure. These misalignments can cause derailments because trains travelling at typical operating speeds cannot negotiate a track that has shifted laterally. Most buckling derailments tend to occur toward the rear of long heavy trains.G. Wolf, The Complete Field Guide to Modern Derailment Investigation (Wolf Railway Consulting, 08 March 2021), p. 289. Track buckling is typically caused by a combination of the following factors:

- train dynamic forces (due to rolling friction, braking, acceleration, and flanging on curves),

- elevated compressive rail forces (for instance during increased ambient temperatures), and

- weakened track conditions (for instance when rail anchors are no longer providing the required resistive force).

All of these factors were present in the area near Mile 101.1 on the day of the occurrence.

The rail creep observed in this area indicates that the track had been under compressive stress for some time. The high ambient temperature on the day of the occurrence and the sharp variations in temperature in the preceding days would have increased this stress. The passage of the heavy train created friction heat from the wheel contact with the rail; these forces added to the compressive stress that was already present. The location of the derailed cars (near the end of the train) indicates that track buckling likely occurred as the end section of the train travelled over the track.

Three weeks before this occurrence, there was another reported track buckling eventTSB rail occurrence R25W0043. on the Fort Frances Subdivision that resulted in the derailment of 11 covered hopper cars on CN train G89041-06 at Mile 73.5.

Track inspections

Track inspections were performed regularly by CN, and the frequency met or exceeded the minimum requirements of the TSR and CN’s Engineering Track Standards (ETS).

The last track inspection prior to the derailment was performed by hi-rail vehicle on 26 June 2025, and no defects were noted.

Track maintenance

CN was aware of the rail creep on the Fort Frances Subdivision and had planned destressing work for 2025, from Mile 98.0 to Mile 135.0. Destressing was conducted from Mile 99.43 to Mile 100.42 on 10 and 11 June. Work was planned to extend to Mile 135.0 but was paused as CN prioritized repairs at another location. This left the section of track from Mile 100.42 to the crossing at Mile 101.46 (the next fixed location), including the point of derailment at Mile 101.1, particularly vulnerable to track buckling; however, the area in the vicinity of the derailment was not protected by a slow order.

Rail anchor adjustments

Rail anchors play a crucial role in preventing rail creep and enhancing track lateral resistance. They hold the rail in place and transmit the longitudinal forces, including those generated by the passage of a train, to the ties. The ties, embedded in the ballast, absorb these forces, which are then transferred to the subgrade.

If anchors are not applied tightly to sound ties, they will not provide the expected restraint.

A study conducted by the University of Texas on rail anchor slip forceUniversity of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV) - University Transportation Center for Railway Safety (UTCRS): Rail Anchor Slip Force Testing (October 2024). highlighted the need to consider anchor performance degradation over time, especially pertaining to repeated removal and reapplication of these anchors.

CN’s ETS specify that rail anchors should be applied uniformly along the rail and firmly against the side of the tie. The ETS also state that anchors can be slid along the rail base only with a mechanical anchor squeeze or spreader, and that anchors that need to be manually adjusted must be removed and reapplied.Canadian National Railway Company, Engineering Track Standards (2019), TS 3.1: Rail Anchors, p. 3.1-1.

The investigation determined that this practice was not consistently followed during post-derailment repairs at Mile 101.8, as some anchors were manually slid along the rail base by up to 4 inches with a sledge hammer.

Safety action taken

On 16 October 2025, the TSB sent Rail Transportation Safety Information Letter 01/25 to Transport Canada (TC). The letter indicated that, given the heavy tonnage carried on the Fort Frances Subdivision and the associated risks that derailments pose, TC may wish to consider reviewing CN’s track inspection and maintenance practices on the Fort Frances Subdivision, particularly those related to rail destressing, securement, and movement, to ensure that rail is destressed in a timely fashion.

In its response on 04 December 2025, TC indicated that it would conduct a track inspection of the Fort Frances Subdivision in 2026.

Safety message

When excessive rail stress is observed, it is important that railway companies proactively implement track protection measures and carry out timely repairs to reduce the risk of derailments.

So as not to compromise the structural integrity of tracks, it is important that track maintenance employees adhere to the appropriate operational procedures for the work they are carrying out, such as when adjusting rail anchors.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on 21 January 2026. It was officially released on 03 February 2026.