Grounding

Passenger vessel Louis Jolliet

Off Sainte-Pétronille, Île d’Orléans, Quebec

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

On 16 May 2013, at approximately 1435 Eastern Daylight Time, the passenger vessel Louis Jolliet ran aground off Sainte-Pétronille, Île d'Orléans, Quebec, while on a cruise with 57 passengers on board. The vessel sustained minor damage to the hull. The passengers and some crew members were evacuated onto 2 pilotboats and a tug. The vessel was refloated at high tide, returned to port under its own power, and resumed operations on 18 May 2013. There were no injuries, and there was no pollution.

Factual information

Particulars of the vessel

| Name of vessel | Louis Jolliet |

|---|---|

| Official number | 170718 |

| IMO number | 5212749 |

| Port of registry | Québec, Quebec |

| Flag | Canada |

| Type | Passenger vessel |

| Gross tonnage | 2112.00 |

| LengthFootnote 1 | 49.53 m |

| Draft at occurrence | Forward: 2.90 m Aft: 4.11 m |

| Built | 1938; Davie Shipbuilding Ltd., Lauzon, Quebec |

| Propulsion | Single-screw diesel engine, 750 kW |

| Maximum complement | Passengers: 1000; Crew: 97 |

| Complement at occurrence | Passengers: 57; Crew: 21 |

| Registered owner/operator | Croisières AML Inc., Québec, Quebec |

Note

IMO: International Maritime Organization

Description of the vessel

The Louis Jolliet was built of riveted steel in 1938 for service as a roll-on/roll-off ferry. It was converted for use as a seasonal passenger/cruise vessel in 1977, primarily making short harbour cruises in the Quebec City area on the St. Lawrence River, as well as offering longer dinner cruises (Photo 1). The vessel is also available as an event venue and may carry up to 1000 passengers.

The main hull of the vessel is subdivided by 7 watertight transverse bulkheads into the following compartments (from forward to aft):

- forepeak

- potable water compartment

- cloakroom/storage compartment

- fuel tank/storage compartment

- sewage water compartment

- pump/storage compartment

- machinery space

- rudder compartment

Below the main deck, there are 3 manually closing watertight doors connecting the following compartments:

- potable water compartment and cloakroom/storage compartment

- cloakroom/storage compartment and fuel tank/storage compartment

- sewage water compartment and pump/storage compartment.

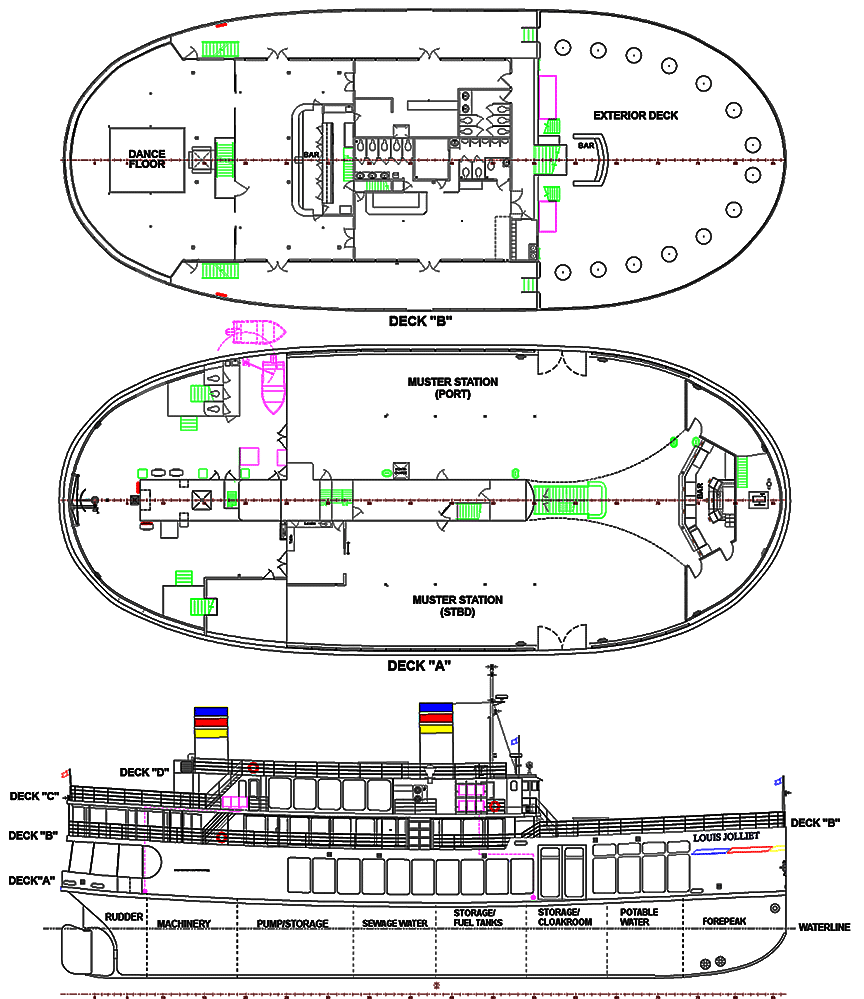

The main deck, deck A, primarily serves passengers as a ballroom/dining room. Deck B comprises passenger spaces such as a boutique, snack bar, and dance floor, and the wheelhouse and crew spaces are on deck C forward, with some passenger spaces aft. Deck D is an open-deck passenger area (Appendix A).

The passenger muster and embarkation areas are located on Deck A, with lifejackets, the rescue boat, and the emergency embarkation ladders stowed there as well. Some lifejackets are also stowed on the forward part of Deck B, and 6 rescue platforms of 150-person capacity each are stowed on the port and starboard sides of Deck C.

Navigational equipment

The wheelhouse of the Louis Jolliet consists of a navigation console forward with a centreline helm position, 2 radars, a global positioning system (GPS), a magnetic compass, an echo sounder, an electronic chart system (ECS), and an automatic identification system (AIS). A chart table is situated against the aft bulkhead, along with alarm and electrical panels.

The vessel was not equipped with a voyage data recorder (VDR) at the time of the occurrence, nor was one required by regulation.Footnote 2 The bridge and other areas of the vessel were equipped with closed-circuit TV, which was helpful to the investigation.

History of the voyage

Familiarization voyages

On the morning of 15 May 2013, the chief mate boarded the Louis Jolliet for his first day of work on board in the role of chief mate, and went to the wheelhouse to meet the master. Following a brief conversation, the chief mate walked around the vessel, self-guided, to refamiliarize himselfFootnote 3 with its layout and equipment, and assisted with various light duties to prepare the vessel for the day's tours. At approximately 1350,Footnote 4 the chief mate reported to the wheelhouse. The master demonstrated how to start up the navigation equipment, and they discussed the chief mate's duties during a voyage, the route to be taken, and the procedures for departure and arrival at the dock. The vessel then departed on a cruise at approximately 1405.

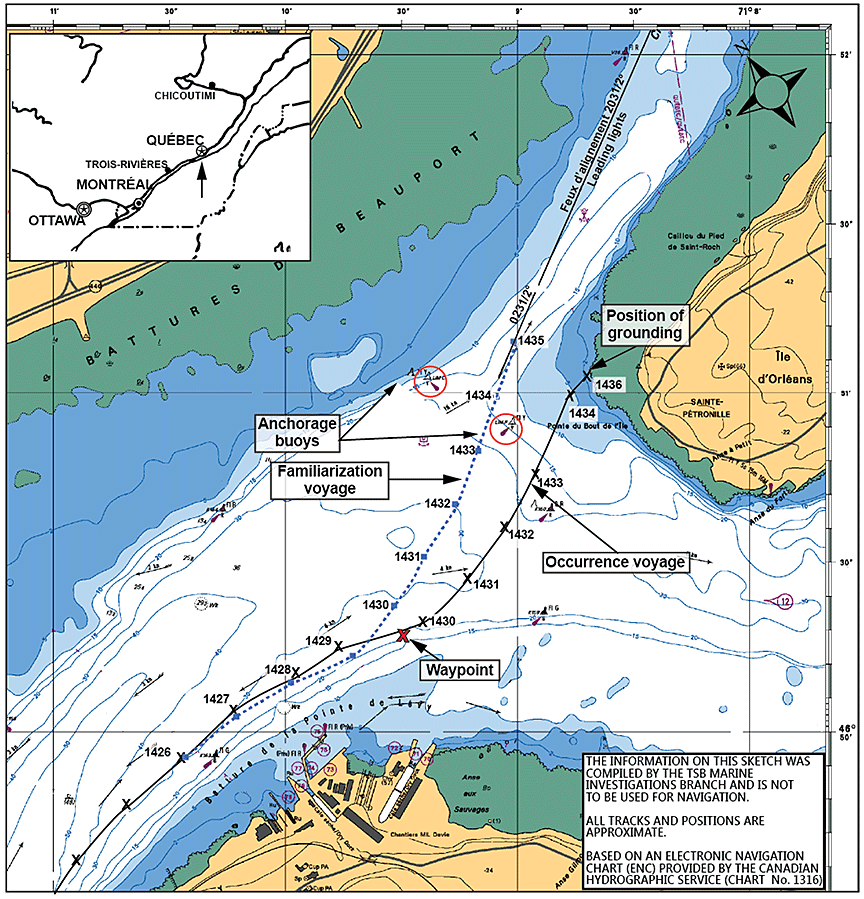

With the chief mate at the wheel and the master guiding him, the vessel was navigated upbound (westerly) along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River for about 10 minutes, until it reached the Quai de la Reine. Then they executed a port course alteration to cross the river, and the master instructed the chief mate to navigate downbound along the south shore, staying inside of the buoys that delineated the navigational channel. The master then left the wheelhouse for about 7 minutes, to check on a passenger who had fallen down.

After having returned to the wheelhouse, and when the vessel was abeam of the shipyard facilities at Pointe de Lévy, the master instructed the chief mate to execute a second port course alteration in order to proceed northeast toward the Chenal de l'Île d'Orléans. The master then instructed the chief mate to follow a route toward the anchorage zone Delta and to look for the Ange-Gardien range marking the Chenal de l'Île d'Orléans.Footnote 5 The chief mate confirmed that he saw the range, and the master emphasized the importance of steering on it because the sea floor was rocky, with sand bars in areas, and was subject to large tides. The chief mate was shown other aids to navigation, such as the 2 yellow anchorage buoys and the port-hand and starboard-hand buoys marking the main channel of the river (Appendix B). The master then showed the chief mate a waypoint that had been placed on the electronic chart to mark the approximate position for making this turn. Before reaching the Pont de l'Île d'Orléans, the master instructed the chief mate to alter course and retrace the route back to the dock, arriving at approximately 1530.

Later that same day, the vessel embarked on an evening cruise, following a different route than the afternoon cruise. Under the master's guidance, the chief mate was at the helm for approximately 1.5 hours of the 2-hour cruise.

Occurrence voyage

At approximately 1405 on 16 May, the Louis Jolliet left the dock at Québec, Quebec, for a harbour cruise following the same route as that of the previous afternoon; the chief mate was at the helm. As was the usual practice, the passengers were counted as they boarded the vessel. The master recorded the number of passengers as 59 in the logbook. As the vessel moved away from the dock, the passenger safety recordingFootnote 6 was played over the public address (PA) system. Upon the vessel's departure, the chief mate and the master were both in the wheelhouse; the chief mate was at the helm and the master was doing paperwork and making phone calls.

In the ebbing tide, the vessel proceeded upbound along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River for about 10 minutes, to the Quai de la Reine. The chief mate executed a course alteration to port that was overseen by the master, who stood at his side. The master then left the wheelhouse for approximately 2 minutes, and when he returned, the chief mate altered course and proceeded downbound along the southern shore of the river.

The master then sat at the chart table with his back to the helm, and began eating his lunch and reading the newspaper. Shortly afterward, the chief engineer entered, seated himself next to the chart table, and began a conversation with the master.

As the chief mate continued to steer the vessel, the master turned periodically and looked out. At about 1429, when the vessel was abeam of the shipyard facilities, the chief mate asked the master if the alteration to port could be initiated. The master looked out, then agreed, and the chief mate then altered to port (Appendix B). The chief engineer left the bridge to do his round in the engine room.

Over the next 4 to 5 minutes, as the vessel crossed the channel in a northeasterly direction, the chief mate searched for the Ange-Gardien range indicating the Chenal de l'Île d'Orléans, but was unable to locate it. He was not utilizing the bridge navigational equipment or charts to position the vessel. At around 1432, the master looked up twice in close succession. There was no communication between the master and the chief mate. At this time, the vessel's course over ground was 035.6° true (T), and its position was approximately 2.1 cables east of the range line.

The vessel continued, and, at approximately 1434, was travelling at a speed of approximately 10 knots and a course over ground of approximately 027°T. The chief mate, who had continued looking out for the range, glanced at the echo sounder and noticed that the water depth was decreasing. He then glanced at the ECS and alerted the master, whereupon the master stood up, looked out, and ordered the rudder hard to port. The chief mate put the helm to port, at which time the vessel struck the bottom and grounded in position 46°51.05′ N, 071°08.69′ W (Photo 2, Appendix B).

Events following the grounding

Immediately following the grounding, the master called to advise the owner of the accident. No alarms were sounded on the vessel. The chief deckhand and the chief engineer proceeded to the wheelhouse, and, following the master's orders, went to check the vessel's watertight compartments for water ingress.

At approximately 1442, about 6 minutes after the grounding, Marine Communications and Traffic Services (MCTS) contacted the vessel and inquired about its status, as the vessel appeared to have stopped. At around the same time, the master was advised by the chief deckhand that there was water present in the cloakroom/storage compartmentFootnote 7 and in the pump/storage compartment forward of the machinery space. The chief engineer then started the main bilge pump. About 10 minutes after the grounding, the master made an announcement over the PA requesting that passengers and crew members gather on Deck B, stay calm, and await further instructions.

Meanwhile, the chief stewardFootnote 8 verified that the watertight door in the storage area was closed. The chief steward then went up to Deck B to check on the other food service crew and speak to the tour guide.Footnote 9 The chief steward then went to the wheelhouse to speak to the master, who asked him to count the food service crew members. When the chief steward returned to the wheelhouse with the number, the master then asked him to return to Deck B with the rest of the food service crew and begin distributing lifejackets. The master gave the same order to the chief deckhand, who had returned from checking the hull for water ingress. The master also ordered him to start preparing the embarkation areas. Lifejackets were brought to the passengers, and another deckhand took the initiative to demonstrate how to put them on correctly, while other crew members checked to ensure that everyone had put them on and secured them properly. The tour guide communicated with the passengers in French, English, and Spanish, passing on instructions, and informing and reassuring them about the situation. Free beverages, including alcohol, were also offered to the passengers.

Some of the master's orders to the crew were relayed using portable radio,Footnote 10 but crew members also went directly to the wheelhouse to find out what to do and then relayed the order as necessary. As the vessel started to heel to starboard in the receding tide,Footnote 11 the master and owner made arrangements with a local operator to transfer the passengers ashore, and the master advised MCTS of this plan. The side doors at the port-side embarkation areas on Deck A were opened, and the emergency embarkation ladderFootnote 12 were deployed in preparation for the evacuation. The rescue platforms were not deployed.

After verifying that the chief deckhand and the chief steward had completed their tasks as ordered, the master made an announcement on the PA ordering the crew to direct the passengers to the muster areas on the main deck (Deck A). After the passengers were gathered, deckhands checked the vessel to ensure that all passengers were present and counted 57 passengers. The number recorded in the vessel's log was 59 passengers, so they recounted and confirmed that there were 57 passengers on board. At 1528, the master contacted MCTS to give the passenger count.Footnote 13

A pilot boat and tug arrived on scene, with a second pilot boatFootnote 14 arriving shortly thereafter. Submersible pumps were transferred onto the Louis Jolliet to clear the water that was present in the cloakroom/storage compartment and also in the pump room / storage compartment, where there was a small ingress of water. At the master's request, the chief mate went below (with a portable radio) to oversee the passenger evacuation.

The evacuation of passengers began approximately 75 minutes after the grounding. The passengers, with their lifejackets on, climbed down the rope ladders at the forward port-side embarkation area and onto the deck of the first pilot boat. When the second pilot boat arrived, passengers also climbed down the rope ladders at the aft embarkation area. In some cases, passengers required additional assistance and were accompanied down the ladder by a crew member. The pilot boats transferred groups of about 10 passengers at a time to the tug, which was waiting nearby in deeper water. The passengers were counted as they descended the ladders.

The embarkation ladders were not long enough to reach the deck of the pilot boat on the port side of the Louis Jolliet, due to the receding tide and opposing heel.Footnote 15 Passengers had to cross between the lowest step of the ladder and the deck of the pilot vessel (a gap of approximately 0.6 metre). The rope ladders were also free to twist and sway, making it difficult for crew members on board the pilot vessels to securely hold the ladders in place as people climbed down.

The tide continued to drop throughout the evacuation and as the heel increased, large items of furniture as well as kitchen equipment, such as dishes, began to fall or move across the deck. In response, several crew members began moving these items to secure locations on the port side. The chief deckhand kept the master (who was in the wheelhouse) informed via portable radio regarding progress in the passenger evacuation, which took about 40 minutes. The crew verified that no passengers had remained on board. The master ordered that all non-essential crew (those associated with food services as well as the tour guide) also be evacuated to the assisting vessels. By approximately 1635 (2 hours after the grounding) a total number of 13 crew members and 57 passengers were evacuated, leaving the master and 7 crew members on board.

In the meantime, the owner boarded the vessel with other company personnel and 2 consulting naval architects to assess the vessel's condition, stability, and options for refloating.

After the evacuation, it was determined that there had been damage to the hull at 2 locations in the bottom of the pump room, each allowing a small ingress of water. The vessel was refloated by the rising tide, and it returned to dock under its own power at approximately 2200.

Environmental conditions

Visibility at the time of the occurrence was good, with westerly winds at around 10 knots, light waves, and some rain showers. Air temperature was 13 °C. The tide was ebbing and, with low tide expected at 1851, resulted in a current of about 2 to 3 knots.

Vessel certification

The Louis Jolliet is inspected annually by Transport Canada (TC) Marine Safety and Security, and at the time of the occurrence, the vessel was duly certified to undertake voyages as a passenger vessel in sheltered waters. The inspection certificate was supplemented by 2 minimum safe manning documents; these documents specified that the vessel was required to carry a crew of 12 for a passenger complement of up to 288, and a crew of 20 for a passenger complement of up to 1000. In all cases, a minimum of 3 certificated officers is required—a master, a chief mate, and a chief engineer. The remainder of the crew complement consisted of deckhands not required to hold a certificate of competency.

Personnel certification and experience

At the time of the occurrence, the master held a certificate of competency as Master, Limited, for a vessel of 60 gross tonnage or more. His experience at sea began when he joined the company in 1996, and he had been in the role of master on the Louis Jolliet since September 2008.

The chief mate held a Watchkeeping Mate certificate of competency, issued in December 2012. He joined the company as chief mate on the Louis Jolliet on 15 May 2013. Prior to that, he had served as a helmsman while a cadet and as a deckhand on board a tour boat. Before joining the company, he had limited navigational experience and no experience navigating in the Chenal de l'Île d'Orléans.

The chief steward had marine experience dating back to May 2011, when he first joined the company. He had completed formal training in marine emergency duties (MED), as well as training provided by Croisières AML in 2011 and 2012. He had acted in the position of chief steward in 2012, but his first day in the role of chief steward during 2013 was the day of the occurrence.

Navigational practices

The navigational practices on the Louis Jolliet were informal and undocumented. The practice was for the master and chief mate to be in the wheelhouse for the duration of the voyage, with the chief mate at the helm for the downbound segment and the master at the helm for the return segment. For departure and docking operations, the master would move to the bridge wing to manoeuvre the vessel and give helm orders to the chief mate. If circumstances arose in which the attention of one of the officers was required elsewhere on the vessel, normal practice was for the chief mate to leave the wheelhouse, maintaining communication with the master using a portable radio.

There was no documented voyage plan. There is a paper chart for the area in the wheelhouse, but the vessel's route was not indicated, nor was the chart used to plot the vessel's position during a cruise. Two waypoints were indicated on the electronic chart; one marked the turning position at the Quai de la Reine and the other marked the turning position at the shipyard facilities. The officers, however, relied primarily on visual references to navigate. The practice was to alter to port once they saw that they were approximately abeam of the shipyard facilities, and then to use the yellow anchorage buoys to guide the vessel toward the entrance to the Chenal de l'Île d'Orléans. The vessel was then aligned with the Ange-Gardien range to navigate the channel.

Company training and familiarization practices

The master had prepared a training manual for new, uncertified crew members. They were also asked to sign a document to indicate that they had read and understood the contents of the manual.

The manual presents an overview of the company, the vessel's organization, and the responsibilities of all crew members. It emphasizes the importance of participation in emergency drills and the reporting of all abnormal occurrences to a superior. It also addresses the use and locations of lifesaving and firefighting equipment, as well as general safety issues on board.

Part 6 of the manual provides a description of the muster list (Appendix C), including the division of responsibilities between 5 designated teams—command, control, intervention, support, and passenger control—and a description of the responsibilities of each team and team leader. It also describes the various alarms, muster stations, and embarkation areas, and the basic steps to take in response to various emergency situations, such as those involving a man overboard, a fire, a collision, or grounding. In the case of a grounding or call to abandon, the manual emphasizes that the master should, according to the gravity of the situation, call for help from external resources and make an announcement to passengers and crew, who should then proceed as outlined on the muster list. Passengers should be directed rapidly to the muster stations, and the crew should distribute lifejackets and ensure that the passengers have donned them in the correct manner. It is also emphasized that only the master is authorized to make an order to abandon the vessel.

None of the crew had been formally trained in passenger safety management, nor is this required by regulation. However, the training manual addresses this subject. The manual designates the chief steward to be in charge of the passenger control team in case of an emergency. It elaborates that this team is responsible for maintaining constant communication with the wheelhouse, reassuring and controlling passengers, and organizing the pre-evacuation of passengers by directing them to the muster stations, if needed. The manual also provides some general information on various aspects of passenger control, such as preventing panic by communicating essential information, and identifying and controlling difficult passengers.

Each year, before the operating season began, new crew members who did not have MEDFootnote 16 training were required to attend a training session in which the master reviewed and discussed the muster list, the training manual, and the emergency scenarios included in the evacuation plan. The session also included a practical component in which the new crew members were familiarized with the vessel, its equipment, and their responsibilities. Returning crew members could also attend these sessions, which may also have been held at other times during the operating season. According to the training manual, the responsibility for ensuring that crew members were adequately trained and familiar with their duties rested with the master and officers (the chief mate and chief engineer).

With respect to crew members who were not required to attend the training described above, the practice aboard the vessel was to give such crew members a tour of the vessel that included a discussion of their specific duties, including their emergency duties. However, there were no written company procedures for the management of their familiarization that indicated, for example, who should conduct the familiarization and when, what subjects should be covered, and how it should be documented.

When the chief mate joined the vessel, he did not receive a copy of the training manual, and the vessel's muster list or evacuation plan were not discussed with him. His familiarization consisted of a tour of the vessel and its equipment, which was conducted by another chief mate a few days before the occurrence on 13 May. The other officer showed the chief mate around the vessel and directed him to various items of emergency equipment. The chief engineer demonstrated how to start the emergency fire pump and the rescue boat motor, and a man-overboard drill was conducted. The chief mate was told that it was his duty to operate the rescue boat in an emergency. On the chief mate's first day of work (the day before the occurrence), he navigated the vessel, under the master's guidance, on the same route as that of the occurrence voyage.

Emergency procedures and drills

Muster list

The muster list (Appendix C) was posted in the wheelhouse and on Deck B. It was developed for the typical crew complement of 20, divided into teams as follows:

| Team | Leader | No. of crew | Muster station |

|---|---|---|---|

| Command | Master | 2 | Wheelhouse |

| Control | Chief engineer | 2 | Machinery space |

| Intervention | Chief mate | 5 | Main deck (dance floor) |

| Support | Chief deckhand | 4 | Main deck (muster area no.3) |

| Passenger control | Chief steward | 7 (up to 84)Footnote 17 | Deck B |

According to the muster list, all passenger safety management tasks associated with the pre-evacuation phase of an emergency are the responsibility of the passenger control team, led by the chief steward. This team may number up to 84 crew members, and its only specified task is to direct passengers to the embarkation areas. The chief mate's responsibilities are to lead the intervention team of 4 deckhands to fight a fire or directly address other emergency situations as required, and in the event of an evacuation, to launch and prepare the rescue platforms at the starboard embarkation areas.

Evacuation plan

The master had developed an evacuation plan for the vessel for the purpose of ensuring the company's compliance with TC.Footnote 18 The specified purpose of the plan is to reinforce the crew's competence in emergency procedures and provide the master with a decision-making tool as events unfold in an emergency.

A copy of the evacuation plan, dated 2010, was kept in the wheelhouse of the Louis Jolliet. The plan provides details of the muster and embarkation areas, as well as of the lifesaving equipment and its stowage locations. It also specifies the specific amount of time required to perform the various tasks that form part of an evacuation.Footnote 19

According to the evacuation plan, the passenger control team is required to:

- direct passengers toward the muster areas,

- distribute lifejackets after the master has made the announcement,

- give instructions in how to put on the lifejackets, and

- verify that they are put on correctly.

The document also contains evacuation plans for 5 specific scenarios. These plans outline, in more detail than the muster list or training manual, the specific tasks of each of the emergency response teams. The tasks are divided into those relevant to the pre-evacuation period and then the evacuation itself, culminating with an estimate of the total time required to effect an evacuation based on the timings of the tasks described above.Footnote 20

In general, the pre-evacuation tasks described in the plans are similar for each scenario. For example, sounding the general alarm is listed as one of the first tasks to be performed by the master. In a grounding situation, however, the plan states that the sounding of the alarm will depend on the scale of the damage. The alarm indicates to the crew that they are to begin to perform their emergency roles and muster at their assigned stations, where the team leaders are responsible for taking a count of their team and reporting to the master.

For the passenger control team, pre-evacuation tasks include directing passengers to the muster areas and once there, informing and reassuring them, and distributing lifejackets. This team is also tasked specifically to make a count of passengers with the help of parents, friends and organizers and, if passengers are missing, to see with the support team about recovering them.Footnote 21

As with the pre-evacuation, the evacuation tasks described in the plans are generally similar for each scenario. For example, the master is to, among other things, sound the abandon-ship alarm, coordinate the launching of the emergency boat and rescue platforms, and give the order to evacuate. His last tasks before leaving the vessel himself are to ensure the exact count of passengers and crew and, once the evacuation is finished, to send a team to check that no one has stayed on board.Footnote 22 The plan further specifies that the chief mate is responsible for leading this team.

The plan divides those duties directly related to evacuation between the passenger control team and the support team. The passenger control team is tasked with verifying that passengers are ready to disembark (i.e., lifejacket properly donned, jewellery and high-heeled shoes removed), directing them toward the embarkation areas and identifying a person (at each embarkation area) to be responsible for counting the passengers. The support team is tasked with counting passengers as they disembark via the emergency ladders into the rescue platforms.

The plan does not contain any checklists or quick reference guides for use by the various teams as an emergency situation unfolds, and the evacuation plan was not referred to in this occurrence. Furthermore, certain key crew members—the chief mate, the chief steward, and the chief deckhand—were unfamiliar with the document and with the specific tasks assigned to them therein.

The evacuation plan also described the organizational structure on board the vessel and the company policies related to emergency procedures training. The plan notes that most of the typical crew complement of 20 has MED training and specifies that those without it are required to participate in the in-house training session. The plan also indicates that practical training in emergency procedures is provided by way of the regular drills that are carried out throughout the operating season.

Drills

Drills were conducted on board the Louis Jolliet on a regular basis, under the direction of the master. Annually, in conjunction with the TC inspection, a boat and fire drill was conducted under the supervision of the master and witnessed by a TC marine safety inspector (MSI). Drills to practise various scenarios, such as those involving a man overboard, fire, or evacuation, were conducted at least once every 2 weeks.

Drills involved the participation of crew members only and were never conducted under circumstances that simulated a voyage with passengers on board. Duties related to the management or control of passengers in an emergency were not practised. At the TC inspection prior to the occurrence, the chief steward participated in the drill by assisting the fireman to don the firefighting outfit and handle the fire hose.

Regulatory requirements for passenger safety procedures and drills

There are 2 sets of regulations under the Canada Shipping Act (2001) regarding procedures and drills for passenger mustering and accounting in an emergency situation: the Life Saving Equipment Regulations and the Fire and Boat Drills Regulations.

The Life Saving Equipment Regulations require every passenger vessel to “have an evacuation procedure for the safe evacuation of the complement from the ship within 30 minutes after the abandon-ship signal is given.”Footnote 23 MSIs verify that the documented procedure is on board during their annual inspection, but they do not approve the procedure. In this occurrence, a TC MSI reviewed the evacuation procedure for the Louis Jolliet and provided some comments, but did not approve it, as this is not a TC requirement.

The Fire and Boat Drills Regulations were amended in 2010 to require the muster list of a passenger vessel to include the assignment of emergency duties that crews need to perform in relation to passengers.Footnote 24 The regulations specify certain duties to be included in the muster list, such as:

- warning passengers of the emergency,

- ensuring passengers have donned their lifejackets correctly,

- assembling passengers at their designated muster stations,

- locating passengers who are unaccounted for and rescuing them,

- keeping order in the passageways and stairways, and

- ensuring that a supply of blankets is taken to the survival craft.

Furthermore, the master of a passenger vessel is required to ensure that procedures are in place for locating passengers who are unaccounted for and rescuing them during an emergency,Footnote 25 and to ensure that, during drills, crew members practise their duties related to passenger safety.Footnote 26

During the annual inspection of a vessel, an MSI verifies that the documented muster list is on board and witnesses the conduct of a boat and fire drill, but does not verify that the muster list contains the information required by regulation. On 30 April 2013, at the last annual inspection prior to the occurrence, the evacuation plan and muster list were verified as being on board, and a satisfactory drill was observed.

Previous occurrences

Procedures and drills for mustering and accounting for passengers

Following an occurrence in May 2003 involving a fire on a cargo deck on the roll-on/roll-off passenger ferry Joseph and Clara Smallwood, a Transportation Safety Board (TSB) investigationFootnote 27 revealed that crew members did not possess the knowledge or skills to adequately perform their emergency duties, and the TSB subsequently expressed its concern about the adequacy of passenger safety procedures and training.

During the March 2006 sinking of the roll-on/roll-off passenger ferry Queen of the North, 2 passengers remained unaccounted for following evacuation procedures and were never found. The TSB investigationFootnote 28 found that those responsible for passengers had difficulties establishing and reconciling the total count and identifying those missing. The Board subsequently recommended that:

[t]he Department of Transport, in conjunction with the Canadian Ferry Operators Association and the Canadian Coast Guard, develop, through a risk-based approach, a framework that ferry operatorscan use to develop effective passenger accounting for each vessel and route.

TSB Recommendation M08-01

The TSB investigation also noted that drills did not cover the full range of skills necessary to muster and control large numbers of passengers. Given the risks associated with poorly coordinated preparations for evacuating large number of passengers, the Board recommended that:

[t]he Department of Transport establish criteria, including the requirement for realistic exercises, against which operators of passenger vessels can evaluate the preparedness of their crews to effectively manage passengers during an emergency.

TSB Recommendation M08-02

As part of TC's response to these recommendations, the Fire and Boat Drills Regulations were amended to require that the muster list duties for passenger vessels include locating passengers who are unaccounted for in an emergency and rescuing them. The amendment also required that procedures and realistic drills related to these duties be implemented. The Board assessed the responses to both recommendations as Fully Satisfactory in July 2010.

In August 2007, the roll-on/roll-off passenger vessel Nordik Express struck Entrée Island, Quebec, damaging its hull below the waterline. The subsequent TSB investigationFootnote 29 identified several shortcomings with respect to duties related to passenger safety, including the following:

- The bridge crew did not sound an alarm, leaving the crew members who were responsible for passenger safety to improvise their response.

- The emergency duty lists did not address tasks related to the preparatory stages of an evacuation.

- A passenger count was not performed.

In October 2012, the roll-on/roll-off passenger ferry Jiimaan grounded on the approach to Kingsville Harbour, on Lake Erie in Ontario. The TSB investigation into this occurrence determined that the shipboard plans and procedures for mustering and accounting for passengers were not comprehensive, and that drills were conducted with only crew members, which meant that crew were not able to practise passenger management duties in a realistic way.

Furthermore, it was determined that TC inspections did not verify that the duties or procedures related to passenger safety as required by the regulations were included in the shipboard procedures. The Board issued a safety concern, stating that if TC marine safety inspectors do not assess muster lists and evacuation plans for compliance and adequacy, and if TC does not provide interpretive guidelines, compliance with passenger safety regulations may be inadequate, thereby negating the potential safety benefits of such regulations.

Safety management systems

The TSB has repeatedly identified the need for domestic vessels to have effective safety management systems (SMS), an issue that has been on the TSB's Watchlist since 2010. The Board has noted that effective oversight of SMS by TC is not always provided, and that an SMS is not required of some companies.Footnote 30 To address this safety issue, the Board also noted the following:

Strong initiatives are required to address the issue of risk awareness and risk mitigation—both of which can be addressed through a formal, systematic approach to safety. TC, vessel operators, and marine management companies must work together to ensure that operating risks are identified and reduced to a minimum through the introduction of effective SMS.Footnote 31

The addition of this item to the Watchlist was the result of a number of investigationsFootnote 32 in which the Board found hazards and risks in the operation of a vessel that had either not been identified or not been addressed by the operator. Other occurrence investigationsFootnote 33 have also addressed shortcomings in the implementation of SMS, whereby operators had not identified hazards associated with an operation, resulting in a lack of mitigation strategies for those hazards.

In the autumn of 2013, TC presented a discussion paper at the Canadian Marine Advisory Council on its proposal to amend the Safety Management Regulations. According to the proposal, a vessel such as the Louis Jolliet, which carries more than 50 passengers and is over 500 gross tonnage, would be required to develop and implement an SMS that is certified and audited as being compliant with the International Safety Management Code.

Analysis

Events leading to the grounding

On the day of the occurrence, after initiating the course alteration to port at the shipyard facilities, the chief mate immediately focused on finding the Ange-Gardien range. The chief mate was unable to visually locate the range and did not utilize the bridge navigational equipment and charts. He continued to give this task priority while the vessel proceeded in the ebb tide, off its intended course, for approximately the next 5 minutes until it went aground. Several factors contributed to these events:

- The deck watch was effectively composed of a single person—the chief mate—who was expected to fulfill all of the tasks of navigation, maintaining a lookout, and steering. The master was present in the wheelhouse, but was occupied with other activities. Despite looking up periodically, the master was not actively participating in the navigation, and neither the chief mate nor the master made use of the other available navigational aids to monitor the progress of the vessel.

- During the minutes between the change of course at the shipyard and the grounding, there was insufficient communication between the master and the chief mate. Both interpreted the other's silence as indicating that the voyage was proceeding as planned.

- There was no assessment of the chief mate's understanding of the navigational requirements for the intended voyage following the familiarization trip. The chief mate understood that he was to look for the range immediately following the course alteration at the shipyard facilities, whereas the practice was to first navigate toward the yellow anchorage buoys.

- There was no documented voyage plan for the chief mate to refer to and use as guidance.

Crew familiarization procedures

On any vessel, familiarization with the working environment and duties are key elements in enabling crew members to adequately fulfill their roles and responsibilities in normal operating conditions, but particularly in emergency situations.

In this occurrence, the chief mate was new to the role and, according to the vessel's muster list and evacuation plan, had significant responsibilities in an emergency. The chief mate was expected to lead a team of at least 5 crew members to fight a fire, prepare rescue platforms on the starboard side, and ensure that watertight doors and manholes were closed, among other things. Otherwise, the chief steward was expected to lead the passenger control team, which could include as many as 84 crew members, and was responsible for the safety of up to 1000 passengers.

However, the chief mate on the Louis Jolliet had not been shown the muster list, and neither he nor the chief steward was familiar with the more detailed provisions of the evacuation plan. For example, the chief mate understood that he was responsible for operating the rescue boat in an emergency, whereas the muster list actually assigns this role to the chief engineer, and the chief steward understood that one of his roles was to assist the fireman to don the fireman's outfit.

Company policy regarding basic safety training was addressed in the evacuation plan; however, it did not include the procedures to follow in order to ensure that key crew members, such as emergency team leaders, are adequately familiarized with their roles. Rather, the responsibility for familiarization was placed solely on the master, and in this occurrence, that familiarization was inadequate. If all crew members are not properly trained in emergency procedures, there is a risk that crew members will not fulfill their assigned roles effectively in an emergency.

Emergency response

During an emergency, the safety of the vessel and its complement (particularly the passengers, who are unfamiliar with the vessel and its emergency procedures) is dependent on prompt and appropriate action by crew members to perform their assigned emergency duties. These duties are carried out under the overall instruction of the master, and on board the Louis Jolliet, as with most vessels, procedures and training dictated that specific duties be commenced when signalled by an alarm bell.

In this occurrence, following the grounding, the master chose not to sound the alarm and communicated with passengers and other crew members by means of a public address announcement a few minutes afterward. In addition, there were some aspects of the response to the grounding that were not consistent with the vessel's emergency plans and procedures, such as the following:

- The decision not to sound the alarm was made prior to an assessment of the scale of damage to the vessel.

- Several crew members, including the chief steward, went to the wheelhouse to seek information and orders before carrying out their emergency tasks.

- The crew did not muster at their stations to account for themselves and prepare for further orders from the master.

- One crew member who was assigned to go to the wheelhouse to assist the master did not do so.

- Some crew members performed functions that had not been assigned to them on the muster list or evacuation plan, either at the request of the master or by their own initiative.

- Passengers were offered alcoholic beverages, which could have affected their ability to evacuate the vessel.

A plan serves to address the known risks of an emergency; deviating from a plan in order to respond to variables is expected, as no procedure will address every aspect. According to the Louis Jolliet's evacuation plan and muster list, decisions regarding the sounding of the alarm and duties of crew members were at the master's discretion. In this regard, the master's decisions on the day of the occurrence were essentially consistent with the evacuation plan and were not detrimental to the response to the emergency; the tasks necessary to ensure the safety of passengers were accomplished successfully.

However, not referring to a plan or following a procedure developed for the express purpose of responding to an emergency incorporates additional risks, such as those of not initiating key elements of the plan, of increasing the workload of the person in charge, of not providing a structured format to a relieving officer when a change in command suddenly arises, of confusion among emergency teams in the event of conflicting orders, and of not detecting errors in the plan or areas that need improvement. If a response to an emergency is not initiated at the earliest possible stage and in accordance with shipboard plans and procedures, there is a risk that the crew and passengers will not be in a state of readiness to react should the situation escalate unexpectedly.

Passenger safety procedures and drills

In an emergency, crew members may be required to make decisions in a high-stress environment. They may have a heavy task load and little previous experience in emergency situations. Furthermore, on a passenger vessel, crew members are additionally challenged by the need to manage large numbers of people of varying ages and abilities. When crews practise duties related to passenger safety in accordance with comprehensive and documented procedures, the likelihood of a successful emergency response is increased.

The emergency plans in effect on the Louis Jolliet at the time of the occurrence had shortcomings in the passenger safety management procedures, specifically with respect to the preparatory phases of abandoning ship. The investigation identified that the vessel's muster list, evacuation plan, and training manual did not offer any specific details on:

- the process by which all spaces of the ship would be searched and cleared of passengers,

- how and by whom people with injuries or disabilities would be assisted,

- how a head count of passengers at the muster station would be accomplished and reconciled with the number of passengers on board, and

- how and by whom any missing passengers would be located and rescued.

Most of these tasks were accomplished on the day of the occurrence. For example, the crew was able to accomplish a sweep of the vessel and resolve the discrepancy between the number of passengers on board and the number recorded in the vessel's log. However, without having documented procedures for the full range of passenger safety management tasks, the company has no means to ensure that these duties could be organized and practised on a consistent basis, if at all. This consequence is especially significant for vessels like the Louis Jolliet that can accommodate up to 1000 passengers, with a passenger control team of up to 84 members.

Furthermore, drills on board the Louis Jollietwere practised only with crew members and did not use passengers or crew members acting as passengers; consequently, the crew members were not able to practise their passenger management duties in a realistic way. Documentation of procedures also provides a tool to evaluate the crew's performance during a drill, to train new crew members, and to refine and improve the procedure itself. A well-documented procedure fosters a shared operational understanding and makes it easier for crew members to familiarize and refresh their understanding of it.

If crew members do not have comprehensive, documented procedures and realistic drills for passenger safety management tasks, there is a risk that crew members will not be able to carry out these tasks effectively in an emergency.

Adequacy of regulatory oversight

Previous TSB investigationsFootnote 34 have identified deficiencies and associated risks in the preparedness of Canadian passenger vessel crews to muster and account for passengers in an emergency situation. In response to TSB recommendations to address the issue, TC enacted regulations requiring that the muster list of a passenger vessel include tasks specific to passenger safety and include procedures that are developed to carry out those tasks.

In this occurrence, a documented muster list and evacuation plan was kept on board the Louis Jolliet; this was verified by TC marine safety inspectors during annual inspections and fulfilled the requirements for the certification of the vessel. However, the documents in use on board the Louis Jolliet included none of the specific duties or procedures related to passenger safety that were required by regulations, with the exception of “assembling the passengers at their designated muster stations.”Footnote 35

If TC oversight to ensure compliance with regulations regarding passenger safety emergency procedures is ineffective, there is an increased risk that these procedures will not achieve their intended purpose.

Safety management

Effective safety management requires all organizations, large or small, to be cognizant of the risks involved in their operations, to be competent to manage those risks, and to be committed to operating safely. These ends may be accomplished with the implementation of an SMS (safety management system)—a means of ensuring safe practices in vessel operations and promoting a safe working environment by establishing safeguards against all identified risks and by continuously improving the safety management skills of personnel ashore and on board vessels. The resulting documented, systematic approach is tailored for the company and the vessel, and helps to ensure that individuals at all levels of an organization have the knowledge and the tools to effectively manage risk, as well as the necessary information to make sound decisions in any operating condition, including both routine and emergency operations.

Currently, TC does not have regulations mandating the implementation of an SMS on domestically operated vessels like the Louis Jolliet. Although it is the operator's commitment that forms the cornerstone of safety management, regulatory frameworks do provide motivation and valuable guidance in the development and implementation of an SMS. In this occurrence, the company had not implemented an SMS and had not established procedures regarding the conduct of the navigational watch, voyage planning, or familiarization of all crew members.

If vessel operators are not mandated to implement SMS, there is an increased risk that hazards will not be identified and risks will not be effectively managed.

Findings

Findings as to causes and contributing factors

- After initiating a course alteration, the chief mate focused on finding a visual reference, the Ange-Gardien range, and did not utilize the bridge navigational equipment to effectively monitor the vessel's progress as it proceeded off course and went aground.

- During this time, the master was not participating in or supervising the navigation of the vessel, and there was no communication between the master and the chief mate. As a result, the deck watch was effectively composed of a single person—the chief mate—who was expected to fulfill all of the tasks of navigation, maintaining a lookout, and steering.

- The master did not assess the chief mate's understanding of the navigational requirements for the intended voyage following the familiarization trip on the previous day, and there was no documented plan for the chief mate to use for guidance.

Findings as to risk

- If all crew members are not properly trained in emergency procedures, there is a risk that crew members will not fulfill their assigned roles effectively in an emergency.

- If a response to an emergency is not initiated at the earliest possible stage and in accordance with shipboard plans and procedures, there is a risk that the crew and passengers will not be in a state of readiness to react should the situation escalate unexpectedly.

- If crew members do not have comprehensive, documented procedures and realistic drills for passenger safety management tasks, there is a risk that crew members will not be able to carry out these tasks effectively in an emergency.

- If Transport Canada oversight to ensure compliance with regulations regarding passenger safety emergency procedures is ineffective, there is an increased risk that these procedures will not achieve their intended purpose.

- If vessel operators are not mandated to implement safety management systems, there is an increased risk that hazards will not be identified and risks will not be effectively managed.

Safety action

Safety action taken

Transportation Safety Board

On 27 June 2013, the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) sent Marine Safety Information (MSI) Letter no. 03/13 to Croisières AML regarding passenger safety issues. The investigation had determined that, with the vessel heeled to about 15°, the length of the rope ladders used to evacuate passengers was too short to reach the decks of the assisting vessels, and that furniture and various sundry items were unsecured and moved or scattered across the deck. These factors served to increase the risk to passenger safety during the evacuation, as well as consuming the attention and efforts of crew. Croisières AML responded that the vessel's equipment and emergency procedures will be revised to address the stowage of items on the deck.

Transport Canada

Transport Canada (TC) issued a “FLAGSTATENET” notice to all TC inspectors and others authorized to carry out inspections to remind them of the requirements under section 7 of the Fire and Boat Drill Regulations. Furthermore, TC has added new fields to the System Inspection Reporting System to remind inspectors to ensure that these requirements are met.

Croisières AML

Since the occurrence, Croisières AML has implemented the following safety actions:

- Tracks for the cruises have been traced onto the marine chart.

- Each crew member is evaluated for their understanding of safety matters on board the vessel. Once evaluated, crew members are required to complete a form wherein they must describe the various roles they may be called upon to fulfill, according to the muster list. They must then sign the form, confirming that they understand the tasks associated with these roles.

- A new procedure was issued to the chief mates of the company's vessels, with the objective of ensuring that crew members are each aware of their positions according to the muster list and to avoid confusion in an emergency. The procedure calls for a meeting with each crew member before each departure in order to count the number of personnel aboard (other than passengers), and to distribute job cards specifying crew members' tasks according to the muster list.

- A training checklist was developed in order to document the familiarization of new officers. It includes a checklist of all of the subject areas to be covered during the familiarization and specifies on-the-job training to be completed.

- With respect to emergency procedures and drills, a summary of emergency procedures was developed, as well as a guidance document for the conduct of the various emergency procedures and drills, including a new pre-evacuation drill.

- Employees have been provided with new equipment for them to wear during emergencies to identify them as crew members.

- Procedures have been developed, aimed at the chief officer of the Louis Jolliet, specifying the tasks to be completed for the following operations: start-up of bridge equipment, departure, arrival, daily start-up, and shutdown.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board's investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on . It was officially released on .

Appendices

Appendix A – General arrangement

Appendix B – Area of the occurrence

Appendix C – Muster list

Note: This is a reproduction of the muster list that was posted on board at the time of the occurrence.

GENERAL EMERGENCY PROCEDURES

- The emergency exercises must be held as per the statutory rules.

- When general alarm is sounded: Crew go to their muster stations and don lifejackets.

- Team leader: Take attendance and report to the captain.

- All emergency signals are done using whistles and microphone.

- Man overboard: Deploy liferings and advise the officer of the watch.

- Inspection after each exercise: Rescue platforms and emergency equipment.

- The captain or responsible officer can order a crew member to execute an emergency function as required.

- The team leaders: distribute the functions as per each member's competence. They are responsible for the performance.

- The watchkeeping personnel will stay at their respective stations and initiate emergency procedures when duly relieved.

- The abandon ship will occur only on the CAPTAIN's orders.

| GENERAL ALARM : | Alarms and Whistle | Seven or more short blasts followed by one continuous blast |

|---|---|---|

| ABANDON SIGNAL : | Alarms/PA System | One continuous blast/Captain's order |

| MAN OVERBOARD : | Alarms | Three prolonged blasts; Emergency Team muster on the bridge |

| RANK | FIRE & EMERGENCY SITUATION | ABANDON |

|---|---|---|

| CAPTAIN |

|

|

| ASST. COOK |

|

|

| RANK | FIRE & EMERGENCY SITUATION | ABANDON |

|---|---|---|

| CHIEF ENGINEER |

|

|

| DECKHAND (ASST. ENGINEER) |

|

|

| RANK | FIRE & EMERGENCY SITUATION | ABANDON |

|---|---|---|

| 1st OFFICER |

|

|

| DECKHAND #1 |

|

|

| DECKHAND #2 |

|

|

| DECKHAND #3 |

|

|

| DECKHAND #4 |

|

|

| RANK | FIRE & EMERGENCY SITUATION | ABANDON |

|---|---|---|

| CHIEF DECKHAND |

|

|

| DECKHAND #5 |

|

|

| GUIDE |

|

|

| WAITER #1 |

|

|

| RANK | FIRE & EMERGENCY SITUATION | ABANDON |

|---|---|---|

| CHIEF STEWARD |

|

|

| WAITER #2 (room Deck B) |

|

|

| WAITER #3 (outside Deck B) |

|

|

| WAITER #4 (room Deck C) |

|

|

| COOK |

|

|

| SNACK BAR CASHIER |

|

|

| BOUTIQUE CASHIER |

|

|

| OTHER CREW MEMBERS |

|

|

| PASSENGERS | Follow instructions from crew | Follow instructions from crew |

[Signature of Master]