Safety issue investigation (SII)

Fishing safety in Canada

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

Since 1992 the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) has made 42 recommendations concerning fishing safety, and many of these recommendations have been acted on. However, despite the efforts of the Board and others in government and the private sector, many of the causes of fishing accidents today are the same as those identified by the TSB two decades ago. Most significantly, between 1999 and 2008, an average of 14 people died in fishing accidents each year. Consequently, in August 2009, the TSB began a broad safety issues investigation into accidents involving commercial fishing vessels in Canada. This report sets out the process followed in the investigation, identifies why certain causes of accidents persist year after year, and provides a way forward that would make the industry safer.

Ce rapport est également disponible en français.

Executive summary

In August 2009, the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) began a broad safety issues investigation (SII) into accidents involving commercial fishing vessels in Canada. The Board was concerned that an average of more than 13 people had died in fishing accidents in Canada each year between 1999 and 2008.

The investigation was conducted by a team of TSB investigators with expertise in commercial fishing, statistical and safety analysis, human factors, marine engineering and naval architecture.

From August 2009 to September 2010, the TSB visited 10 locations in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Quebec, Manitoba and British Columbia. Investigators consulted over 300 fishermen, industry representatives and government agencies, including safety training institutions and trainers, fish processors, union representatives, members of fishing associations, provincial and federal regulators, marine underwriters and safety researchers. This report refers to these groups collectively as the “fishing community”.

Since its creation in 1990, the TSB has produced over 370 investigation reports and made 42 safety recommendations concerning fishing vessels; it has also issued at least 100 safety information and safety advisory letters on fishing safety. The TSB reviewed these reports, their findings and the recommendations as part of this investigation. It also reviewed fishing safety information and best practices in Canada and other countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, Iceland, New Zealand, Norway and South Africa.

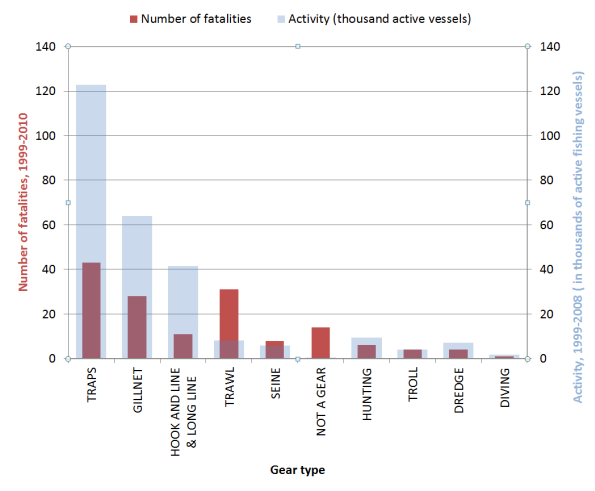

In addition, the TSB gathered extensive data on fishing vessel operations, including types of vessels, gear, fishing location and crew size. This information made it possible to identify various accident-related rates and assess the risks associated with commercial fishing vessel operations in Canada. However, these rates do not accurately reflect fishermen's exposure to risk. Calculating exposure to risk is difficult because current measures of activity (e.g., number of crew and days at sea engaged in fishing operations) are not readily available and do not cover all aspects of fishing operations.

The Board identified the significant safety issues and goals associated with fishing accidents in Canada as follows:

| Safety issue | Safety goal |

|---|---|

| STABILITY Fishing safety suffers when the principles of stability are not well understood, applied, or presented in a practical format. |

Fishermen understand the principles of stability and apply this understanding to make fishing operations safer. |

| FISHERIES RESOURCE MANAGEMENT Fishermen are put at risk when fisheries resource management measures do not consider safety at all levels, from policy through to practice. |

Identifying and reducing safety risks are integral to fisheries resource management. |

| LIFE SAVING APPLIANCES Life saving appliances that are not properly designed, carried, fitted, used or maintained for fishing operations put lives at risk. |

Life saving appliances are properly designed, carried, fitted, used and maintained for fishing operations. |

| REGULATORY APPROACH TO SAFETY The fishing community relies mainly on regulations to address safety deficiencies, an approach that is less than effective. |

A coordinated and consistently applied regulatory framework supports a safety culture in the community. |

| TRAINING Training is often not practical, and is not practised and evaluated regularly; such training is ineffective in reducing accidents. |

Training is effective and is reinforced by regular practice. |

| SAFETY INFORMATION Safety information is not always practical or communicated in an easy-to-understand way, and does not always reach its target audience. |

Practical, understandable safety information reaches those in the fishing community who need it. |

| COST OF SAFETY The fishing community often sees safety as an obligatory cost (time and money) rather than as a key part of managing fishing operations. |

The fishing community accepts the cost of safety as an integral part of fishing. |

| FATIGUE Fishermen frequently work when fatigued, and the safety risks of doing so are regularly underestimated. |

The risks of fatigue are understood and managed. |

| FISHING INDUSTRY STATISTICS The lack of coordinated, quality data on fishing vessel accidents makes it difficult for organizations to identify and communicate safety risks and trends. |

Accident data are collected, analyzed and communicated in a coordinated way to help the fishing community identify hazards and risks. |

| SAFE WORK PRACTICES Unsafe work practices continue to put fishermen and their vessels at risk. |

Safe work practices are routine and more lives are saved. |

Most of these issues have been addressed in past TSB investigations. Furthermore, these issues have been recognized internationally as, for example, in the United Kingdom's Marine Accident Investigation Branch report, “Analysis of UK Fishing Vessel Safety 1992 to 2006”. However, the fishing community is complex, and it must recognize that its members react to changes made by others in the community and that these reactions could introduce safety issues that have not been foreseen. This TSB investigation reveals these complex relationships and interdependencies among issues and demonstrates that addressing them on an issue-by-issue basis tends not to be productive. For example, the unsafe condition of unsecured deck openings is linked to stability which is, in turn, linked to at least four other safety issues: training, work practices, cost of safety, and regulatory approach to safety. Only if all five safety issues are addressed can accidents related to unsecured deck openings be expected to decline. Based on this insight, there is limited value in the TSB issuing new recommendations that attempt to deal —in isolation —with the two safety issues that have resulted in the greatest number of fatalities: stability and life saving appliances.

This investigation has highlighted the variability in attitudes and behaviours towards safety across Canada's fishing community. To yield significant change, a recommendation must address a deficiency by taking into account that it is linked to a number of safety issues. It also must be received by the fishing community and acted upon using a coordinated approach.

A number of encouraging, collaborative initiatives in different regions of the country aimed at instilling a safety culture have been identified in this investigation. Such initiatives have evolved independently throughout Canada and differ in their structure, scope and representation. It has also become clear that not all provinces or local offices of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) and Transport Canada (TC) are involved to the same degree in fishing safety. However, this report has also highlighted gaps where further action to enhance safety is clearly required.

The Board believes that it will take focused and concerted action to finally and fully address the safety deficiencies that persist in Canada's fishing industry. Therefore, the Board strongly urges the federal and provincial governments and leaders in the fishing community to establish effective regional governance structures aimed at ensuring those working in the fishing industry can and will work safely.

With these governance structures in place, the fishing community would be well placed to put in motion the safety actions necessary to achieve the goal for each safety issue and to foster an industry safety culture where:

- both the interconnected nature of safety issues and the need to address them in a complete and comprehensive manner are widely accepted;

- perceptions of safety are more consistent and take on a broader perspective;

- better resources and mechanisms to identify, report, understand and analyze risk are available to help focus work practices on reducing defined risks;

- safe work practices become commonplace.

These actions are summarized as follows:

Establish consistent, understandable and practical programs in the following areas and ensure that they are widely accessed and used in the fishing community, for

- stability awareness;

- enable good work practices to take root in the fishing community;

- training;

- the timely dissemination of safety information;

- ensuring that the cost of safety is consistent throughout the community and is shared to the greatest extent possible;

- fatigue awareness;

- risk awareness; and

- adequately addressing the importance of

- safety drills, particularly with respect to the launching of liferafts;

- the benefits of personal flotation devices (PFDs), emergency position-indicating radio beacons (EPIRBs) and immersion suits; and

- the maintenance of all life saving appliances (LSAs) onboard, as part of good work practices.

Share information and consult among fishing community members with respect to

- fishing safety, regulatory requirements and compliance/enforcement with a view to establishing consistency and eliminating duplication;

- the costs associated with safety;

- the risks associated with fatigue and the best ways to manage those risks;

- best work practices;

- the need for new regulatory initiatives;

- the content of those regulations and the resources associated with compliance; and

- the understanding and awareness of those regulations by the community.

Ensure that

- the equipment required to be carried onboard vessels is practical for use by fishermen;

- provisions for the wearing of PFDs are consistent among the various regulatory authorities;

- appropriate interim measures are put in place to address safety deficiencies until such time as the necessary regulatory changes can take effect; and

- enforcement of interim measures, such as those laid out in Transport Canada's Ship Safety Bulletin 04/2006,Footnote 1 as well as the standing regulations is consistent.

Establish and implement standards, regulations, procedures, guidelines or policies as necessary

- to verify that liferafts are being serviced as required;

- to ensure that stability booklets intended are simple, clear and practical;

- for the identification and reduction of safety risks associated with fisheries resource management measures and for the training of resource managers in this area;

- for the collection and statistical analysis of accident data; and

- for the carriage of immersion suits and EPIRBs.

Scope

This investigation is limited to Canadian-flag vessels involved in commercial fishing that do not exceed 24.4 m in length or 150 gross tons.

In 2008, there were 15 800 active commercial fishing vessels in Canada and over 52 800 commercial fishermen registered by either DFO, Bureau d'accréditation des pêcheurs et des aides-pêcheurs du Québec (BAPAP) or the Professional Fish Harvesters Certification Board (PFHCB).Footnote 2 Fishermen are typically independent, self-reliant people who work in an environment that can be dangerous. The requirements that apply to where and when they can fish, and how much total allowable catch is available and what price, are changing—and so are the prices they can get. At the same time, they have to comply with regulations concerning the size of their vessel, the equipment that must be aboard, and the number and qualifications of crew required to operate it.

The Board has made 42 recommendations aimed at improving the safety of these fishermen. Many of these recommendations have been acted on, but there remain 12 that, in the Board's view, have not been addressed in a fully satisfactory way.Footnote 3 For a summary of fishing-related recommendations, see Appendix A.

Despite the efforts of the Board and others in government and the private sector, many of the causes of fishing accidents today are the same as those identified by the TSB two decades ago. Most significantly, between 1999 and 2008, an average of 14 people died in fishing accidents each year.

The number of accidents involving loss of life on fishing vessels remained too high, and this prompted the TSB to conduct an extensive investigation into commercial fishing across the country. This report sets out the process followed in the investigation, identifies why certain causes of accidents persist year after year, and provides a way forward that would result in a safer industry.

The report is intended for those in a position to motivate improvements in fishing safety —that is, the fishing community. For the purpose of this report, the fishing community is considered to be composed of any group or individual with an interest in the industry such as fishermen and their families; fishermen's associations and unions; professional certification boards; safety associations; industry sector councils; owners; processors; buyers; builders; naval architects; workers' compensation boards; regulators; educators and training providers; insurers; equipment designers and manufacturers; and the TSB itself.

The report repeatedly uses the terms “unsafe condition” and “safety issue.” These terms are important for understanding this investigation and are defined as follows:

- Unsafe condition: a condition or situation that has the potential to cause an accident. For example, a hatch cover left unsecured while a vessel is underway is an unsafe condition. If water were to downflood through the unsecured hatch into the hold, the vessel could become unstable and capsize.

- Safety issue: a term used to categorize a number of objects, situations, or actions important to fishing safety. For example, watertight integrity, downflooding, raised center of gravity, overloading, vessel modifications are grouped under the safety issue “stability”.

Methodology

This investigation differed from individual TSB investigations in that it was not triggered by a particular accident. Rather, it sought to answer a particular question: after 20 years of investigations and reports on the causes and contributing factors of fishing accidents, why do accidents keep happening for the same reasons?

To investigate this question, the TSB conducted the following major activities:

- Consultations with over 340 members of the fishing community of which approximately 70% were fishermen across Canada

- Statistical analysis of all reported accidents from 1999 to 2010

- Analysis of TSB accident investigation reports to identify recurrent safety deficiencies

- Review of past Board recommendations and the resulting corrective actions, to assess residual risks

- Literature review and survey of national and international safety bodies to identify best practices.

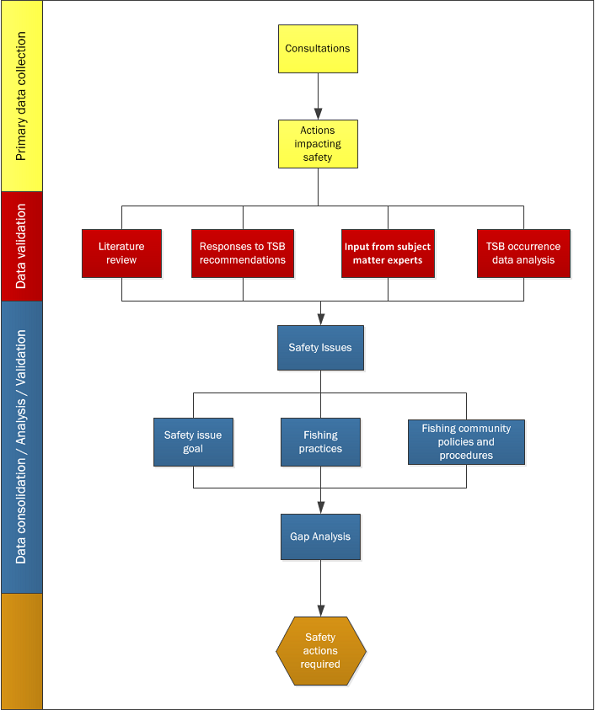

The investigation was divided into phases: primary data collection, validation, consolidation and analysis (Figure 1).

Consultations

Consultations were held with fishermen in Gander and St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador; Dartmouth, Nova Scotia; Îles-de-la-Madeleine and Rimouski, Quebec; Gimli, Manitoba; and Campbell River, Prince Rupert, Richmond and Vancouver, British Columbia. Local organizations played a key role in making sure interested fishermen participated.

The consultations involved groups of 5 to 25 people, with federal, provincial and regional officials and service providers taking part as observers. Separate debriefing meetings were held with the observers to capture the impact fishermen's observations might have on policies and procedures of other fishing community members. Although the participants did not make up a scientifically valid sample of all fishermen in a defined fleet, they were active in their communities and provided important perspectives to compare with the views of fishermen elsewhere in the country.

The consultations, which consisted of guided discussions, were open-ended and asked participants to identify

- how fishermen recognize, evaluate, apply and promote safety information;

- things that get in the way of fishermen taking these actions; and

- opportunities for current and future fishing community members to promote and support safety practices.

These sessions helped the TSB to better understand

- the decisions that fishermen must make to ensure a safe and successful fishing season;

- the impact of those decisions on fishing operations and safety on board; and

- how and what fishermen learn from accidents that have taken the lives of other fishermen.

Additional consultations were held with other members of the fishing community to help the TSB better understand

- the role that TSB safety information plays within their organization;

- how organizations identify and rank safety issues;

- factors that limit or strengthen the ability of organizations to act on TSB safety information; and

- how organizations assess the effectiveness of their safety actions.

The TSB analyzed transcripts of all consultations to identify fishing community actions (fishing practices, community procedures and community policies) that have impacted or have the potential to impact fishing vessel safety. For example, actions with negative implications for safety such as crews operating vessels while fatigued, inconsistent application of regulations, and vessel adaptations to accommodate DFO management measures were mentioned alongside actions that had positive implications for safety such as inclusive briefing sessions before and after fishery opening and modifications to season openings to accommodate weather conditions. Well over 100 of these (positive and negative) actions impacting safety were identified.

Data validation

During the data validation phase, the TSB reviewed research, government publications, regulations, responses to TSB recommendations, and trade literature to better understand the context of the actions impacting safety that were identified in the consultations. Subject-matter experts were further consulted for explanations of such things as fisheries management plans, harvesting details and training programs. Where possible, TSB data were used to further assess the prevalence of the actions impacting safety.

Data consolidation and analysis

During the data consolidation and analysis phase, the validated actions impacting safety were categorized into 10 safety issues and a safety goal was defined for each. The extent to which fishing practices and fishing community policies and procedures prevented the achievement of that goal was assessed. Gaps were then identified where more safety action is required, either in terms of fishing practices or community procedures and policies.

Statistical analysis of accident and incident data

The TSB Marine Safety Information System (MARSIS) was the primary source of accident and incident data analyzed in this investigation. However, data from various other sources, such as the DFO landing database, its vessel registry and the TC registry, were were gathered to compile and consolidate with TSB data.

Historical data are updated whenever there is new information on an occurrence. Consequently, the statistics used in this investigation may differ slightly from those reported in previous TSB publications.

When the data were revisited, it also became clear that refinements were needed in some cases. For example, fatality statistics in British Columbia captured by various safety organizations with different mandates (Canadian Coast Guard, Coroners Service, WorkSafeBC) were examined in greater detail and reconciled with TSB fatality data. This resulted in some new fatal accidents being added to the MARSIS database.

To locate missing information and to augment the data in MARSIS, the TSB took the following steps:

- Original TSB hard-copy files and electronic records were examined for missing data, in particular commercial fishing vessel and vessel registration numbers (CFV/VRN numbers), in order to link MARSIS data with DFO landing data.

- For accident records where the length of a vessel or its gear was not specified, the MARSIS database was examined for previous accidents involving the same vessel. If there were no previous accidents, the DFO registry and the DFO landing database were queried, in that order, to identify the missing variables.

- For accidents where the type of gear involved remained unknown, DFO landing data were used to identify the gear type most likely in use at the time of the accident. This was accomplished by identifying the gear type in use, as recorded in the DFO landing data, on the date of the accident. If there was no record for the accident date, the 10 days before and after the accident were examined to identify what gear type was in use then. If the gear type could still not be identified, the examination was extended to the previous two years.

- A similar process was used for accident records that did not specify any species type.

Plotting of accident data

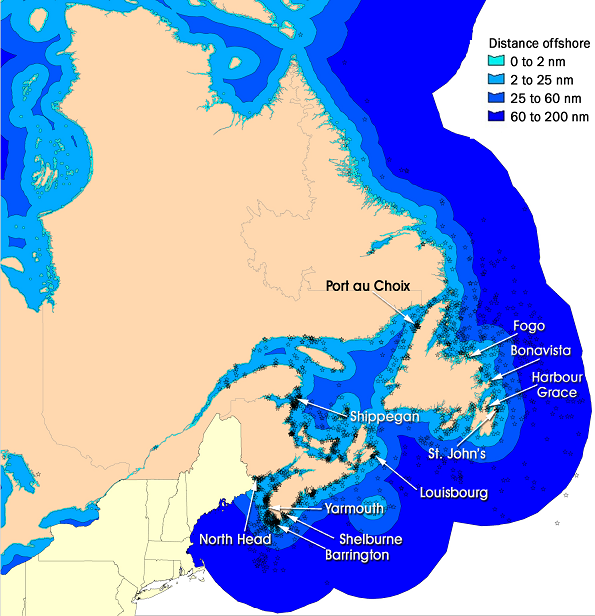

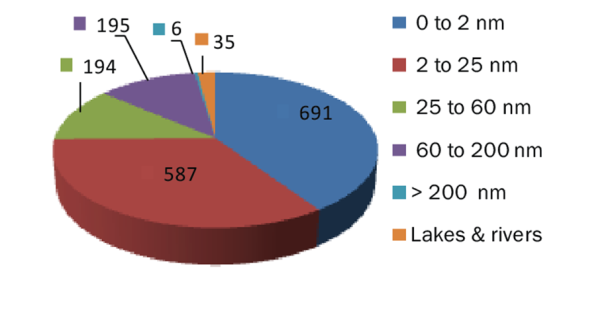

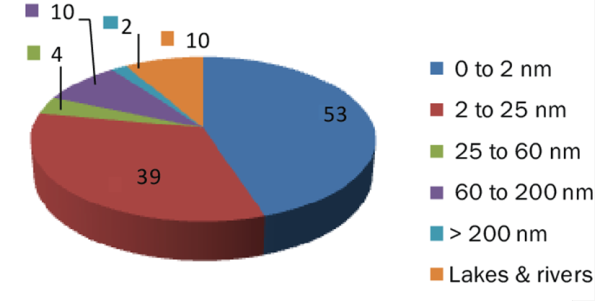

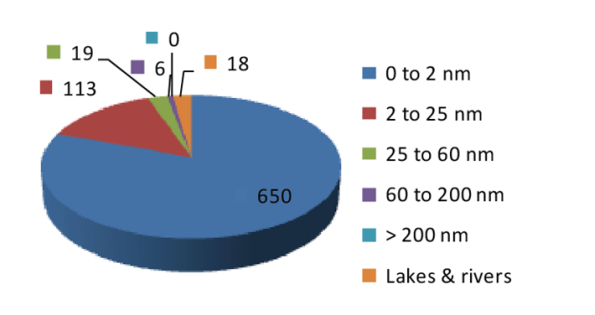

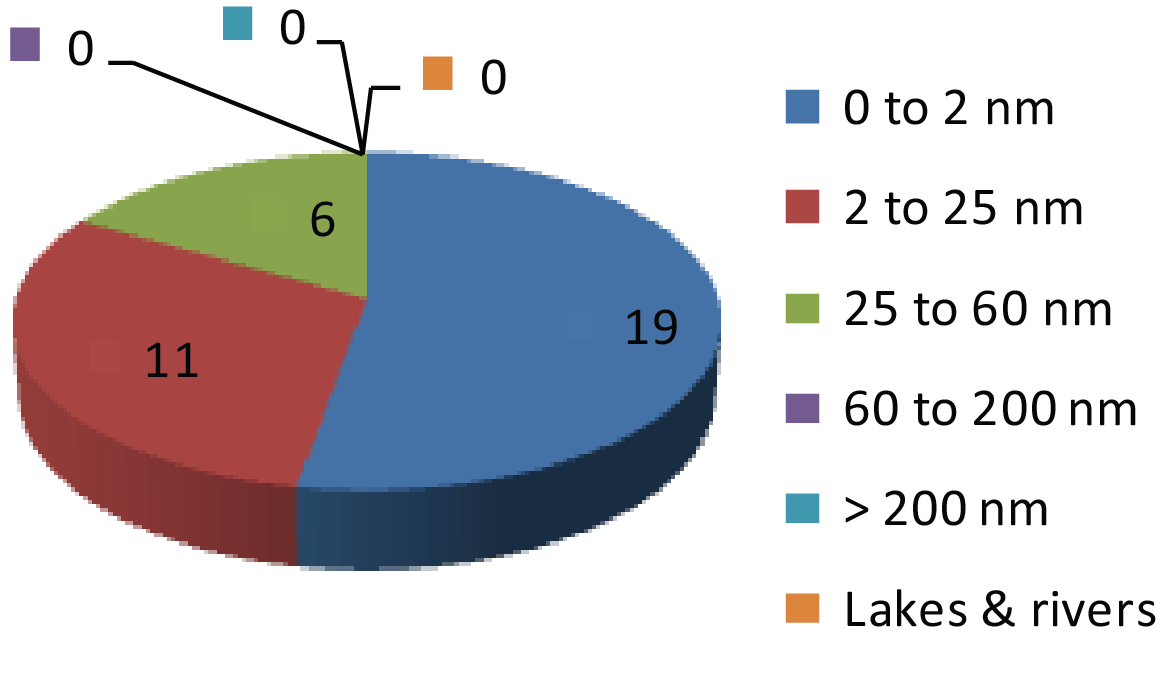

MapInfoFootnote 4 was used to group accidents based on their distance from shore. The following zone ranges were developed after consulting with TC and DFO (Appendix B, figures B.9 to B.14):

- on land (in lakes and rivers)

- 0 –2 nautical miles (nm) from shore

- 2 – 25 nm from shore

- 25 – 60 nm from shore

- 60 – 200 nm from shore

- > 200 nm from shore.

Calculation of accident rate

Accident rates are used internationally to compare workers' exposure to risk within and across industries. An accident rate is often described as a ratio of the number of accidents over the total number of full-time employees (part-time employees are converted by percentage to a full-time-equivalent (FTE) number). The total number of FTE employees is a measure of activity. Using FTE employees as the baseline reference (denominator) for calculation of accident rate assumes that the average full-time employee is exposed to the same hazards over the same period of time as another.

The FTE measure is a difficult number to assess in the fishing industry because the industry is seasonal, exposure to hazards is inconsistent, and labour–time data are not documented.

Consequently, this investigation used two baseline (denominator) measures as estimates of fishing activity:

- the number of registered fishermen

- the number of active vessels.

Fishery landing data

Fisheries landing data from the DFO were integrated with TSB accident reporting data to further understand the fishing contexts (species, gear, vessel type and length and location) of the accidents.

For a detailed statistical analysis of accidents, see Appendix B.

Analysis of TSB investigation reports

All 40 fishing-related TSB investigation reports from 1999 to 2008 were reviewed in detail to identify safety deficiencies present across multiple accidents.Footnote 5 The persistence of these deficiencies was confirmed during consultations with the fishing community. In addition to this detailed review, other TSB reports outside the 10-year period were consulted and are cited within this report.

Review of Board recommendations

Since its creation in 1990, the Board has made 42 safety recommendations concerning fishing vessels. The regulators' responses to the Board's recommendations were assessed , and it was found that risks associated with certain deficiencies persisted. These deficiencies were confirmed during consultations with the fishing community.

Literature review and survey of best practices

A questionnaireFootnote 6 was developed to identify how international accident investigation bodies

- categorize accidents;

- rank safety categories;

- focus their safety messages; and

- assess the effectiveness of their safety support actions.

The questionnaire was given out at the June 2010 Marine Accident Investigators' International Forum conference in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Responses came back from the U.K. Marine Accident Investigation Branch, the Japan Transport Safety Board, the South African Maritime Safety Authority and the United States Coast Guard.

Besides distributing this questionnaire, the TSB conducted literature reviews and consultations to identify international practices that have made, or are expected to make, a measurable difference to fishing safety. For example, New Zealand's FishSAFE encourages fishermen to participate in a workshop where they learn FishSAFE guidelines.Footnote 7 Then, with the help of a mentor, they integrate the safety guidelines into their fishing operations. Attending the workshop, applying the guidelines and conducting a self-assessment makes fishermen eligible for a 10% reduction in their accident insurance levy.

Commercial fishery context

Overview

The commercial fishing industry in Canada consists of a large number of small owner-operators and a few large companies. Vessels under 24 m in length make up more than 98% of the fishing fleet.

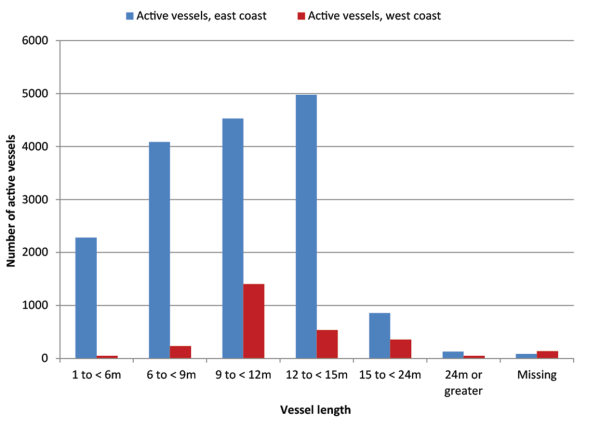

For the most part, fisheries are seasonal, based on when different species are available for harvest. Still, fishing remains vital to the economic, social and cultural well-being of over 1000 coastal communities in Canada. The value of commercially landed seafood in 2008 was just under $1.9 billion,Footnote 8 of which 70% was from fishermen who own and operate their own vessels. Between 1999 and 2008, there were, on average, over 53 000 registered commercial fishermen and over 16 800 active commercial fishing vessels per year. More detailed statistical breakdowns of the regional distribution of active vessels, by average vessel-length, appear in Appendix B (Figure B.15).

Communities affected by the fisheries include those First Nations communities that are increasingly claiming access to coastal fishing rights. For example, the Supreme Court's 1999 Marshall decision confirmed for the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet First Nations a treaty right to fish as opposed to a privilege to fish.Footnote 9 Over the last decade, DFO has been working with Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities on both coasts to redistribute commercial fishing licences and quotas, develop mentoring programs, and help with vessel and gear purchases and training to ensure that Aboriginal commercial fisheries are economically sustainable.

The Atlantic region has been marked by a shift away from harvesting traditional fish species such as cod, due in large part to the decline in fish stocks and subsequent actions taken to protect the fisheries. As a result, fishermen have shifted to harvesting species that offer a reasonable return such as shellfish , notably crab and shrimp . To date, DFO policy is aimed at ensuring that fishing operations stay in the hands of fishermen rather than corporate entities (e.g., fish processors) that are not actively involved in fish harvesting.Footnote 10 In this region, DFO issues fishing licences almost exclusively to individuals who are vessel owner-operators.

In the Pacific region, on the other hand, there is no separation between fishermen and corporate entities not actively involved onboard the vessel during fish harvesting operations . Furthermore, full-time employment opportunities have fallen dramatically in this region because of declining access to fishery resources, a decrease in salmon prices and supply, and a series of DFO measures aimed at rationalizing fleets and redistributing licences and quotas. During the TSB's Pacific consultations, owners and operators reported that it is becoming harder to attract qualified crew due to their reduced ability to offer sustained, full-time employment. In addition, the reduction in the time fishermen spend at sea means that fewer are trained and available to take on key roles such as watchkeeper.

A 2005 report by Praxis Research and Consulting found that in 2003, the average employment term for crews in the Atlantic region was 12 to 15 weeks a year , while in the Pacific region, it was from 12 weeks on longline vessels (halibut/sablefish) to six weeks on gillnet vessels.Footnote 11 During the TSB's consultations, some salmon fishermen reported fishing seasons as short as 32 hours.

Operating environment

Fishermen operate in a harsh physical environment and harvest, load, transfer and store their catch while their vessel is at sea.

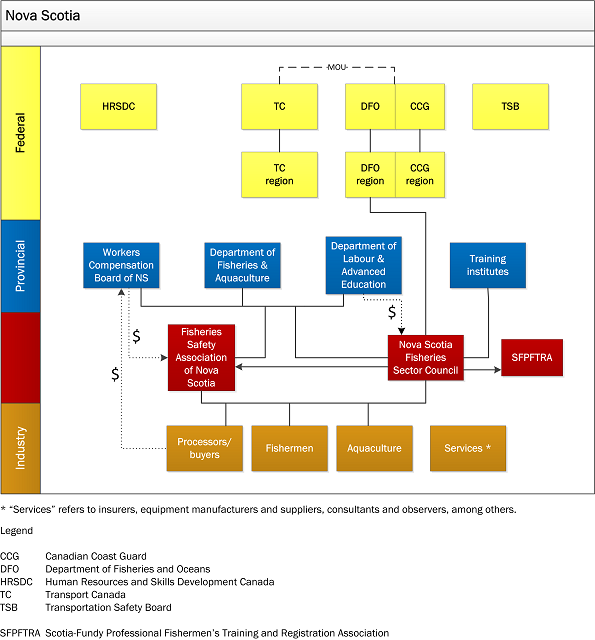

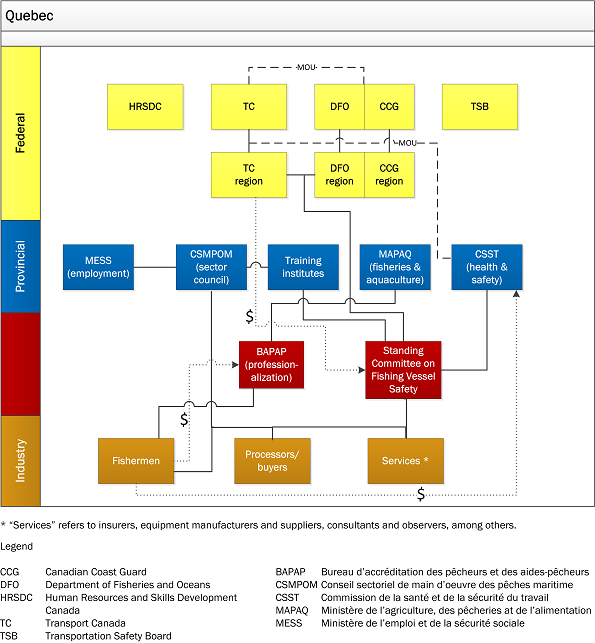

In addition, Canadian fishermen deal with complex regulatory environments. Several federal and provincial government departments and agencies have either a direct or indirect bearing on fishing safety. Industry associations, unions, training providers and certification boards all play critical roles in the safety of the fishing community.

Fishermen are also subjected to changing economic and market conditions for resources that in many instances are unpredictable and increasingly scarce. These forces influence fishermen's priorities, choices and decisions as they attempt to make a living and operate safely.

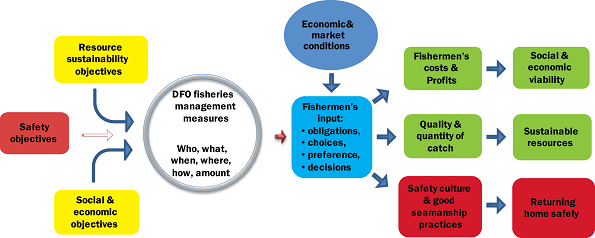

Figure 2 depicts the complex fishing community of which Canadian fishermen are a part and the forces that shape their operating environment.

Roles and responsibilities

As discussed earlier, a number of government departments (at both the federal and provincial levels), agencies and non-government bodies play a role in the governance of fishing safety in Canada. This section highlights the main roles and responsibilities of these different fishing community members.

Fishermen and authorized representatives

Fishing vessel masters have been and continue to be ultimately responsible for their own safety, the safety of the vessel and the safety of the vessel's crew members. The Canada Shipping Act, 2001,Footnote 12 clearly sets out the responsibilities for safety that are incumbent upon the authorized representative,Footnote 13 the master and the crew. This legislation obliges authorized representatives and masters to ensure that all applicable regulations are complied with and that the vessel is operated in a safe and diligent manner. This legislation also obliges crew members not to jeopardize the safety of the vessel or others on board. Some provinces have similar requirements.

A fisherman's effectiveness in carrying out safety responsibilities, however, is influenced by the support and encouragement received from other members of the provincial/regional fishing community.

The investigation revealed examples of how fishermen are moving towards recognizing and addressing their safety responsibilities. For example, fishermen have developed—and facilitate—a voluntary stability education program; they also purchase and use non-required LSAs ; and participate more frequently in regional training. As well, consultation between fishermen and regional DFO resource managers has resulted in safety action being included in integrated fishery management plans (IFMPs). It is the interaction between fishing community members in addressing safety issues that helps build a strong safety culture.

Federal entities

Department of Fisheries and Oceans

In Canada, federal jurisdiction over seacoast and inland fisheries was established under the Constitution Act, 1867 (formerly known as the British North America Act, 1867). The mandate of DFO Footnote 14 was set out in the Government Organization Act, 1979.

The Fisheries Act, the main statute administered by DFO, covers matters such as fish allocation and licensing. Under the Fisheries Act, DFO is responsible for managing, conserving and developing the fisheries on behalf of Canadians. At the same time, the Department is aware that it has a role to play in incorporating safety into the development of fishery management plans and policies.Footnote 15

Section 7 of the Fisheries Act gives the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans broad powers to distribute the wealth of “common property resources” in the form of fishing licences and quotas. Once the fish are caught and become the property of fishermen, the buying, processing and selling of fish fall under provincial jurisdiction.

National headquarters manages national, strategic policy and programs, but DFO is organized regionally to implement fisheries management measures such as assessing stocks, establishing total allowable catches, developing and implementing fishing plans, and evaluating results.

Under current legislation, DFO is responsible for all fisheries management measures. However, the Department is moving toward shared stewardship of the resource, especially with regards to habitat enhancement and the cost of management. Under such an arrangement, the provincial/regional fishing community will be more involved in fisheries management decision-making at appropriate levels. It will also contribute its specialized knowledge and experience, and will share in accountability for outcomes.

Transport Canada

Transport Canada (TC) is the federal department with regulatory authority in the area. Key responsibilities of TC, among others, are:

- the regulatory regime, which includes the development of regulations and standards for vessels and crew to support national laws and policies;

- oversight, which includes issuing licences, certificates, registrations and permits; conducting audits, inspections and surveillance; and taking action when rules are broken; and

- outreach, which includes promoting safety and security as well as educating the public and increasing public awareness regarding these issues.

TC program delivery is managed out of the regional offices; Atlantic, Quebec, Ontario, Prairie and Northern and Pacific.

The TC Marine Safety Program derives its authority from numerous acts, including the Canada Shipping Act, 2001, the Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act, the Navigable Waters Protection Act, the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act, the Safe Containers Convention Act, the Pilotage Act, the Canada Labour Code (Part II) and the Coasting Trade Act.

TC drafts and enforces regulations that establish minimum safety standards for small fishing vessels. Currently, the regulations that apply most directly to small fishing vessels are the Small Fishing Vessel Inspection Regulations and the Marine Personnel Regulations. Over the past eight years, in an attempt to improve the regulatory regime and fishing vessel safety, TC has been developing new Fishing Vessel Safety Regulations which will include requirements for constructing, equipping and manning fishing vessels in Canada.

The Canadian Marine Advisory Council (CMAC) is Transport Canada's national consultative body for marine matters; it meets semi-annually in Ottawa. It is primarily involved in discussions associated with the development and implementation of international and national rules and regulations. One of its seven standing committees is on fishing vessel safety. The majority of those parties interested in fishing vessel safety attend CMAC on a regular basis and participate in the standing committee. In addition to these national meetings of CMAC, Transport Canada also hosts consultation meetings with industry and other government participants in each of its regions.

Canadian Coast Guard

The Canadian Coast Guard (CCG), a special operating agency within DFO, provides maritime services for users of Canadian waterways. It supplies fishermen with key safety services, especially in the areas of aids to navigation, search and rescue (together with the Department of National Defence), marine communications and traffic, ice-breaking and ice management. CCG operations are managed by regional offices : Newfoundland and Labrador, Maritimes, Quebec, Central, and Arctic and Pacific.

Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary

The Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary (CCGA) is a major player in Canada's national search and rescue response network. It is made up of 5000 volunteer pleasure craft operators and commercial fishermen who use their vessels for CCGA activities. CCGA units are distributed across five geographic regions : Newfoundland and Labrador, Maritimes, Quebec, Central, and Arctic and Pacific. In addition to its search and rescue activities, CCGA provides marine safety equipment demonstrations and safe boating courses, and participates in boat shows and safe boating displays. On behalf of the CCG , it also conducts courtesy examinations of pleasure craft and small fishing vessels in order to prevent accidents and loss of life. CCGA promotes its unique identity and mandate to the Canadian public through the media and at public events across the country.

Human Resources and Skills Development Canada

Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC) is a federal department whose mandate includes promoting human resources planning and program development. HRSDC provides fishermen with income stabilization through the Employment Insurance system. The vehicle for delivering HRSDC programs in the fishing industry are industrial sector councils at both the national and provincial levels. Although not a primary objective, most sector council mandates include the enhancement of fishing safety.

Canadian Council of Professional Fish Harvesters

The Canadian Council of Professional Fish Harvesters (CCPFH) was initially formed as a federation of regional fish harvester organizations but has since been designated by, and receives partial funding from, HRSDC as the national human resources sector council for the fish harvesting industry. The National Search and Rescue Secretariat of the Department of National Defence has made financial contributions through its New Initiatives Fund. The CCPFH's mission is to ensure that fishermen have the appropriate knowledge, skills and level of commitment to meet the human resource needs of the Canadian fishery of the future. They advocate on behalf of fishermen to federal, provincial and territorial governments on issues of common concern, actively participate in National CMAC meetings, provide structure and leadership for the development of a program of professionalization, and advocate for training. In conjunction with Memorial University's Fisheries and Marine Institute, the CCPFH's lead project is the development of an interactive fishing vessel stability simulator.

National Research Council – Institute for Ocean Technology

National Research Council's Institute for Ocean Technology (NRC–IOT) provides research, evaluation and development tools to be used to improve safety and regulations governing the workplace at sea. NRC–IOT is currently working with TC and the fishing community to identify populations of fishing vessels at very low risk of stability-related accidents. Another area of research at NRC–IOT is the evaluation of how wind and waves affect heat loss in persons wearing immersion suits. This work will eventually lead to methods of assessing survival times under different conditions while wearing a survival suit.

Transportation Safety Board of Canada

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) is an independent agency created to advance transportation safety by conducting accident investigations to determine the underlying risks and causes. In its marine investigations, the TSB relies on occurrence reporting requirements and all members of the fishing community to gather the raw data required for analysis. The Board then communicates the results of its findings publicly with the aim of reaching the change agents capable of reducing the risks. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability.

Provincial entities

The organizations, associations, councils, committees, alliances, departments, federations, institutes and boards that make up the fishing community of each province vary in scope, role and involvement. This section identifies the key groups among them and describes the role that they play within the fishing community, particularly with respect to safety. Although each province has an established workplace safety or workers compensation board, their involvement in the fishing industry will be expanded upon separately. Illustrations of the governance structure in British Columbia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia and Quebec are in Appendix C.

British Columbia

Oceans and Marine Fisheries Branch, Ministry of Environment — The Oceans and Marine Fisheries Branch is responsible for the overall leadership of provincial government strategies and initiatives related to ocean resources and marine fisheries, as well as seafood industry development.

BC Seafood Alliance – The BC Seafood Alliance is an umbrella group for fishermen associations, seafood processors, marketers and exporters representing some 90% of the commercially harvested seafood in BC. The Alliance mandate covers conservation and sustainable use of BC seafood, sector advocacy and promotion, and fishing safety through Fish Safe.

Fish Safe — Fish Safe is an industry-designed and implemented fishing safety initiative that is administered by the BC Seafood Alliance. Formed in 2005, this safety association is funded by industry, which enables it to leverage support from federal and provincial agencies, including the National Search and Rescue Secretariat at the Department of National Defence. Its mandate is to provide safety programs and tools relevant to fishing so that fishermen can take ownership of safety. The following are some of the safety programs and tools that they have initiated, facilitated and delivered.

- The Real Fishermen campaign — posters, brochures and mugs featuring fishermen wearing PFDs.

- Safety drill events — organized with the fishing community. One example was a fleet-wide event coordinated with fishing companies, DFO and fishermen for an “abandon ship” competition prior to the season opening : prizes were given for the fastest drill and to the crew member on each vessel who donned their immersion suit the fastest.

- The Stability Education Program — a hands-on, interactive four-day voluntary program developed by fishermen for fishermen, which enhances authenticity and uptake, and is supported by TC, WorkSafeBC and the TSB. The program has been delivered to approximately 900 participants since 2011.

- The Safest Catch program — this two-day voluntary mentoring program provides a fisherman-trained safety advisor to work with vessels and crew to develop a customized safety orientation, safety procedures and drills program for their specific vessel, including an orientation on all life-saving appliances. The program has been delivered to approximately 170 vessels since 2011.

- The Safe on the Wheel program — a hands-on, interactive five-day voluntary program for both experienced and inexperienced fishermen on the “rules of the road ”, taught using an actual fishing wheelhouse. The course also incorporates discussion on the issues of human factors and the management of fatigue. Participants receive a Small Vessel Operators Proficiency (SVOP) certificate upon successful completion of this program.

- The Safety Pays program — recognizing the value of Fish Safe programs in reducing risk, this program offers a 10% discount on Harlock Murray Underwriting Insurance upon proof of participation in both the Stability Education and Safest Catch programs.

- Training and on-board tools — items such as DVDs, guides and damage control kits.

Fish Safe Advisory Committee — a fishing safety consultative forum, facilitated by Fish Safe, which meets quarterly and includes representatives of all the members of the fishing community in the province. In addition to guiding the development of Fish Safe's activities, it brings the fishing community together to exchange information and discuss the development of a fishing safety strategic plan. Sub-committees are struck on specific issues as required.

Manitoba

Fishermen's interests in Manitoba are represented by Lake Manitoba Commercial Fishermen's Association (LMCFA) or Manitoba Commercial Inland Fisher's Federation (MCIFF). Both groups are members of the CCPFH.

New Brunswick

In New Brunswick, there are numerous, localized fishermen's associations representing the interests of the fishermen, such as advising DFO on fisheries management issues.

Newfoundland and Labrador

Professional Fish Harvesters Certification Board — In 1996, the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador enacted the Professional Fish Harvesters Act, creating the Professional Fish Harvesters Certification Board (PFHCB). This organization promotes the interests of fishermen as a professional group; develops, evaluates and recommends courses under the professionalization program; and issues three levels of certificates of accreditation to qualifying fishermen based on an applicant's experience and training. An applicant must also demonstrate that he derives 80% of his income from fish harvesting. DFO, in turn, mandates that individuals obtain a PFHCB certificate prior to issuing fishing licences and quotas. The PFHCB may conduct inquiries based on its code of fishing ethics and take disciplinary action, which includes fines and the temporary or permanent suspension of a certificate. The PFHCB also works closely with the CCPFH and Memorial University's Fisheries and Marine Institute to promote fishing safety through initiatives such as safety videos and a stability simulator. The PFHCB is governed by a board of 15 members appointed by the government. Seven members are representatives of the accredited collective bargaining unit for fish harvesters (currently the Fish, Food and Allied Workers Union (FFAW)), one is a representative of the Association of Newfoundland & Labrador Fisheries Co-operatives, two are provincial (Fisheries and Aquaculture, and Education), three are federal (two DFO, one HRSDC) and, additionally, there is one from a training institution and one representative–at-large chosen by the Minister of Fisheries and Aquaculture.

Newfoundland and Labrador Fish Harvesting Safety Association (proposed) — In December 2010, $1 million funding over three years was made available from the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador and the provincial Workplace Health, Safety and Compensation Commission to support the establishment of the Newfoundland and Labrador Fish Harvesting Safety Association (NL–FHSA). An initiative to establish the NL–FHSA is being led by PFHCB in collaboration and consultation with a broad range of fishing community members including fishermen (owner/operators and crew members), union representatives (FFAW), seafood processors, trainers (MI) and researchers (SafetyNet), as well as two provincial government representatives (Service NL and Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture) and federal government representatives (DFO/CCG and TC). The objective of the safety association would be to provide advice to the provincial and federal levels of government on health and safety issues, promote best practices for safety onboard fishing vessels, and support research on fishing industry safety.

Memorial University — Memorial University's Fisheries and Marine Institute (MI) offers training courses for fishermen in Newfoundland and Labrador through its community-based education programs, which are supported by industry and government. In collaboration with the Canadian Council of Professional Fish Harvesters (CCPFH), the New Brunswick School of Fisheries (CCNB) and Transport Canada, MI has developed an interactive fishing vessel stability simulator. The aim of the project is the production of electronic simulations of vessel operations and fishing activities in different fleets in various regions of Canada to better understand how they affect stability. MI recently (2011) completed a pilot online Fishing Master IV course, and has also delivered training for the Technical Certificate in Harvesting, as well as safety workshops and seminars, and has been instrumental in the production of a safety video.

SafetyNet — The SafetyNet Centre for Occupational Health and Safety Research at Memorial University (SafetyNet) is dedicated to improving the safety of workplaces and the health of workers in Newfoundland and Labrador and Atlantic Canada through broad-based partnerships among researchers and stakeholders in communities, government, industry and labour. Since 2001, SafetyNet has collaborated with the PFHCB on a number of projects including SafeCatch, a project which was designed to deepen understanding of trends in search and rescue incidents, injuries and fatalities in the Newfoundland and Labrador fisheries between 1989 and 2005.

Northwest Territories and Nunavut

The Department of Industry, Tourism and Investment participates in marketing efforts and supports the industry by offsetting operations, maintenance and capital replacement costs through the Northwest Territories Fishermen's Federation, the representative body for the Great Slave Lake commercial fishing industry.

In Nunavut, the Fisheries and Sealing division of the Department of Environment focuses on developing viable and sustainable industries that will ensure that all revenues and opportunities derived from territorial resources benefit Nunavummiut. The division works towards maximizing economic opportunities for Nunavummiut while upholding the principles of conservation and sustainability.

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia Fisheries Sector Council —The Nova Scotia Fisheries Sector Council (NSFSC) is dedicated to planning and implementing human resource development strategies to ensure that fishermen have appropriate knowledge, skills, and level of commitment to meet the human resource needs of the Canadian fishery of the future. The council's board of directors includes fishermen, processor, aquaculture and union representatives. The council also has advisory members from DFO, the Nova Scotia departments of Fisheries and Aquaculture and Labour and Advanced Education as well as the Nova Scotia School of Fisheries. In the 1990s, NSFSC was heavily involved in the coordination of safety training when the federal government made resources available that allowed it to purchase training for fishermen. Nova Scotia was the lead province in the achievement of close to 60% compliance of fishermen trained in MED prior to 2002. Since that time, there has been a shift to the provincial government, which is supporting training for the current workforce. As a result, the NSFSC is now working to educate fishermen on training and certification requirements, and is developing tools and a coordinated approach to help fishermen meet the requirements. This council coordinates the Scotia-Fundy Professional Fishermen's Training and Registration Association (SFPFTRA) Network Coordinator outreach program and serves as its director.

Fisheries Safety Association of Nova Scotia — The mandate of the Fisheries Safety Association of Nova Scotia (FSANS) is to enhance safety through prevention education, research, advocacy, communication and increased awareness, thereby making the industry more attractive for new employees. The FSANS is funded by mandatory membership fees collected from employers by the Workers' Compensation Board of Nova Scotia (WCBNS). FSANS was formed in 2010 to address safety issues in the harvesting, seafood processing and aquaculture sectors. The FSANS has a 15-member board which includes five representatives each from harvesting and processing, three from aquaculture and/or services and two from the NSFSC. Ex-officio representatives include the NS Department of Labour and Advanced Education, NS Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture and the WCBNS. The FSANS partnered with WCBNS and Labour and Advanced Education to produce an advertising campaign featuring hard-hitting safety messages such as, “What's harder? Telling your crew to put on lifejackets or telling their families they aren't coming home?”

Ontario

Ontario Commercial Fisheries Association (OCFA) is the representative body in Ontario. The OCFA advocates for the industry and presents industry's interests and views to government, the media and consumers.

Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island Fishermen's Association — The Prince Edward Island Fishermen's Association (PEIFA) was originally formed in the early 1950's and recognizes the benefits of an organization that represents all six regions within Prince Edward Island (PEI). In 2004, the provincial government passed the Certified Fisheries Organizations Support Act. The PEIFA is the only organization recognized to represent 1300 core fishermen in PEI. This association meets 10 times a year, communicates with other fishing organizations, and represents and communicates with the federal government with one united voice.

Quebec

Bureau d'accréditation des pêcheurs et des aides-pêcheurs du Québec — Created in 1999 by provincial statute, the Bureau d'accréditation des pêcheurs et des aides-pêcheurs du Québec (BAPAP) is the professional certification board for fishermen in Québec, reporting to the ministère de l'Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l'Alimentation du Québec (MAPAQ). The objective of this organization is to standardize the professionalization of fishermen, to establish the conditions for fishermen certification, and to issue certificates and booklets in confirmation of the skills of those requesting to work as commercial fishermen. Currently the BAPAP recognizes 3 levels of qualifications and issues certificates to over 1800 fishermen depending on the experience and training of applicants. BAPAP requires applicants to hold a professional fishing diploma or proof of equivalent competency to qualify for a fisherman's certificate.

Standing Committee on Fishing Vessel Safety — The Quebec Regional Standing Committee on Fishing Vessel Safety is the primary vehicle for consultation and the exchange of information between government authorities and most of the fishing community. It is chaired by TC and co-chaired by CCG. DFO, the Commission de la santé et de la sécurité du travail (CSST, which is the province's workers' compensation board), and five representatives from the Quebec fishing community make up the rest of the executive steering committee.

Training institutes — In Quebec, the ministère de l'Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport (MELS) offers secondary students a vocational training program in the fishing profession. Successful graduates of the program receive BAPAP certification. One school that provides this program, L'École des pêches et de l'aquaculture (school of fisheries and aquaculture), in Grande-Rivière, features a training vessel equipped with different types of fishing gear and a navigation simulator. The school offers, among other training, the apprentice fisher course representing 1605 hours of education and training. This course is aligned with TC requirements and prepares graduates to write the examination for the Fishing Master IV certificate of competency.

Conseil sectoriel de main d'œuvre des pêches maritime du Québec — The mission of the Conseil sectoriel de main d'œuvre des pêches maritimes du Québec (CSMPOM) is to examine the industry to determine and implement actions for the enhancement and development of the human resources with the fishing industry. It is a provincial sectoral committee with a board of directors comprising 13 members, including two fishermen association representatives.

Others

Eastern Fishermen's Federation — The Eastern Fishermen's Federation (EFF) was formed in 1979 primarily to provide a voice for the many diverse fish harvester organizations throughout the Maritime and Gulf regions. This federation currently represents 22 organizations and more than 2100 fishermen. The EFF focuses its safety actions on communications and the need for a wheelhouse safety management system that provides tools to fishermen to better understand the overall impacts on safety of all aspects of vessel operation.

Scotia-Fundy Professional Fishermen's Training and Registration Association — The objectives of the Scotia-Fundy Professional Fishermen's Training and Registration Association (SFPFTRA) are to improve the capacity of fishermen, improve the image of work in the fishery, and to promote and strengthen a training culture amongst fishermen. The association recently completed a Network Coordinators outreach program that had six regional coordinators providing safety tools and information on training and certification, eco-labeling/certification, safety at sea, and quality initiatives at sea at the wharf level. This regional program was supported by Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, DFO, Nova Scotia Department of Labour and Workforce Development, and both the Nova Scotia and New Brunswick departments of Fisheries.

Workplace safety and workers' compensation boards

The courts have recognized the jurisdiction of the provinces to regulate certain aspects of the commercial fishery including those related to labour relations, workplace safety and workers compensation. However, the various provincial and territorial legislative regimes differ with respect to these issues, with some taking a more comprehensive approach than others. For example, in provinces where fishermen are recognized as employees, they usually fall under provincial workers' compensation arrangements. This may not be the case in provinces that regard them as independent business owners.

British Columbia

WorkSafeBC establishes, implements, and enforces fishing safety regulations.Footnote 16 A memorandum of understanding (MOU) was signed with TC in 2006 clarifying the responsibilities of each regulator. There are 3.25 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees working with the fishing community, including approximately 5000 fishermen on 2000 vessels. WorksafeBC partners with the fishing community and supports incentives like the BC Seafood Alliance's Fish Safe Program in claims/assessments and prevention areas. Through WorkSafeBC's health and safety association partnership program the seafood processors/buyers have the ability to voluntarily levy themselves an extra assessment which provides the core funding ($250,000 to $400,000 per year) for Fish Safe. WorksafeBC attends Fish Safe Advisory Committee and national and regional CMAC meetings. It also conducts vessel inspections and accident investigations, and through its mandatory

Manitoba

The Workers' Compensation Board of Manitoba has limited involvement in the fishing industry and has no specific fishing regulations. The Ministry of Labour has conducted some vessel inspections, but relies on TC to enforce regulatory compliance. There is no MOU with TC or mandatory workers' compensation program in this region. The fishing industry in Manitoba is composed of approximately 3000 fishermen on 2500 vessels.

New Brunswick

WorksafeNB's Occupational Health and Safety Act defines place of employment as “any building, structure, premises, water or land where work is carried on by one or more employees, and includes a project site, a mine, a ferry, a train and any vehicle used or likely to be used by an employee”. According to WorksafeNB this definition excludes fishing vessels and does not give it the jurisdiction to inspect fishing vessels or enforce the Act. Although a regulatory gap is recognized by the Government of New Brunswick and WorksafeNB, there are no plans to propose any legislative amendments that would close it. There is no MOU with TC and no mandatory workers' compensation program. Only fishing enterprises with at least 25 employees are required to have coverage, but some fishermen voluntarily register for insurance coverage. The fishing industry in New Brunswick is composed of approximately 6600 fishermen on 1800 vessels.

Newfoundland and Labrador

In this province, the responsibility for fishermen's health and safety is shared between two departments : the Workplace Health, Safety and Compensation Commission (WHSCC) provides prevention measures, partners with industry, funds industry incentives and administers a mandatory workers' compensation program that provides insurance to fishermen injured on the job. In 2010, the WHSCC made available $1 million funding over three years toward the establishment of a fishing safety association. Fish buyers must register with the WHSCC and pay assessments based on the value of fish purchased from commercial fishers. In addition, employers who operate a fish processing plant or factory freezer vessel must register and pay assessments based on the payroll of its plant workers. Service NL (formerly known as the Department of Government Services) implements and enforces occupational health and safety regulations,Footnote 17 including those pertaining to fishing. There is one FTE employee working with the fishing community, which includes approximately 17 000 fishermen on 6000 vessels. At this time, the province has not entered into an MOU with TC with respect to matters of fishing safety.

Northwest Territories and Nunavut

The workers' safety and compensation commissions in these territories have no intervention within the fishing industry, but they do administer a mandatory workers' compensation program that provides insurance to fishermen who are registered with the commission. There is no MOU with TC. The fishing industry in Northwest Territories and Nunavut is composed of approximately 150 fishermen on 100 vessels.

Nova Scotia

The Workers Compensation Board Nova Scotia (WCBNS) has no specific fishing regulations, and relies on TC and the provincial Department of Labour to regulate the fishing industry. There is no MOU with TC or mandatory workers' compensation program. A fishing enterprise with at least three employees is required to have coverage. In addition, some fishermen voluntarily register for insurance coverage. There is less than one FTE employee working with approximately 13 000 fishermen on 4500 vessels. The WCBNS believes in an industry -led safety association model and, along with the Nova Scotia Fisheries Sector Council, has developed and supported the formation (2010) of the Fisheries Safety Association of Nova Scotia (FSANS). WCBNS continues to explore opportunities for improvements within the sector and is planning an overall refresh of its provincial Occupation Health and Safety Strategy in 2012, which is expected to benefit the fishing sector.

Ontario

The interventions of the Workplace Safety Insurance Board (WSIB) within the fishing industry are limited, and the WSIB has no specific fishing regulations. The Ministry of Labour has conducted some vessel inspections but relies on TC to enforce regulatory compliance. There is no MOU with TC but the WSIB does administer a mandatory workers' compensation program in this region for fishermen who are registered with the Board. There is less than one FTE employee working with approximately 300 fishermen on 120 vessels.

Prince Edward Island

The Workers Compensation Board under the province's Occupational Health and Safety Act excludes fishing. There is no MOU with TC and no mandatory workers' compensation program. Some fishermen voluntarily register for insurance coverage if they qualify and the current OHS regulations cover general vessel inspections. The fishing industry in Prince Edward Island is composed of approximately 4500 fishermen on 1300 vessels.

Quebec

Since 2000, the Commission de la santé et de la securité du travail (CSST) has significantly expanded its involvement in fishing safety. It established and implemented fishing-specific guidelines primarily through a handbook entitled Health and Safety on Fishing Boats in 2008 and recently in 2011 an MOU was signed with TC clarifying each regulator's role and responsibilities. The CSST has one FTE employee working with the fishing community including approximately 3200 fishermen on 1200 vessels. CSST attends the Quebec Regional Standing Committee on Fishing Vessel Safety meetings as well as national CMAC meetings. It also conducts accident investigations and administers a mandatory workers' compensation program that provides insurance to fishermen injured on the job.

Accident and fatality rates

Commercial fishing is recognized by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) as one of the most dangerous occupations in the world. To determine the extent of the danger in Canada, the TSB examined data on fishing-related accidentsFootnote 18 and deaths in this country from 1999 to 2010. The overall rates and trends are presented below. More detailed statistical breakdowns appear in Appendix B.

It is difficult to compare fishing accident, fatality and fatal accident rates in Canada with those around the world. That is largely because different countries measure the number of fishermen and the level of fishing activity, both key parts of calculating the rates, in different ways.Footnote 19 The accident, fatality and fatal accident rates used in this investigation can be used to track safety trends and improvements over time within Canada, however.

This investigation measured the number of fishermen in Canada by gathering data on the number of marine and freshwater commercial fishermen registered by either DFO, Bureau d'accréditation des pêcheurs et des aides-pêcheurs du Québec (BAPAP) or the Professional Fish Harvesters Certification Board (PFHCB). It measured the level of fishing activity by gathering data on active vessels, namely those DFO-registered fishing vessels with a unique CFV/VRN (vessel registration number) that have at least one recorded landed catch in a given calendar year.

One drawback of using active vessels to measure fishing activity when calculating accident rates is that it does not fully account for exposure to risk, because it does not reflect the number of days a vessel operates in a given year. Similarly, the number of registered fishermen does not capture the time each fisherman spends at sea. Nonetheless, “active vessels” and “registered fishermen” are currently the best measures of fishing activity available to the TSB.

Initially, the period analyzed was from 1999 to 2008. Subsequently, preliminary data became available for 2009 and 2010 and these have been included in the data analysis.

Accident rates

From 1999 to 2010, 2514 fishing-related accidents were reported in Canada (Table 1); the accidents involved 2691 fishing vessels, 2599 of which were Canadian.Footnote 20

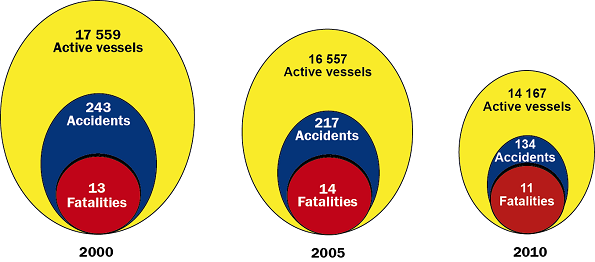

As shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, the period 1999 to 2010 saw an overall decline in both the number of accidents reported to the TSB each year and the number of active fishing vessels in operation.

| 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered fishermen* | 57 707 | 58 884 | 58 860 | 54 207 | 55 033 | 53 770 | 52 805 | 51 677 | 53 820 | 52 107 | 51 245 | 50 118 | |

| Active vessels** | 18 892 | 17 559 | 17 326 | 16 746 | 16 243 | 16 540 | 16 557 | 16 472 | 16 514 | 15 800 | 15 050 | 14 167 | |

| Accidents | 284 | 243 | 244 | 233 | 252 | 233 | 217 | 205 | 170 | 164 | 135 | 134 | 2514 |

| Fatal accidents | 12 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 112 |

| Fatalities | 14 | 13 | 18 | 15 | 12 | 17 | 14 | 10 | 7 | 14 | 9 | 11 | 154 |

* Estimated number of marine and freshwater commercial fishermen recorded with DFO (majority of income may not necessarily come from fishing operations), based on annual statistical reports, DFO Economic Analysis and Statistics, Policy Sector. Number of freshwater and northern fishermen in 1999-2002 and 2009-2010 were extrapolated from available data for 2003-2008.

** Number of DFO-registered fishing vessels with a unique CFV/VRN number that have at least one recorded landed catch in a given calendar year.

Fatality rates

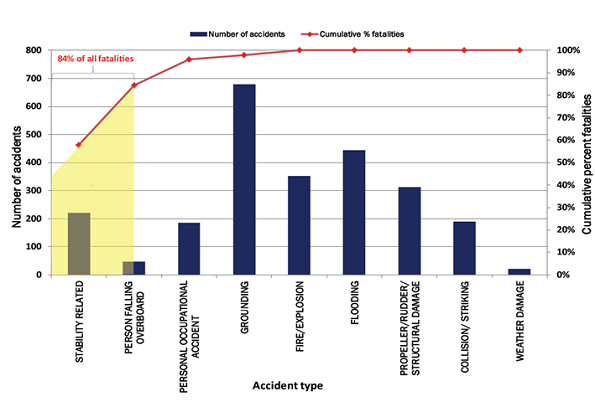

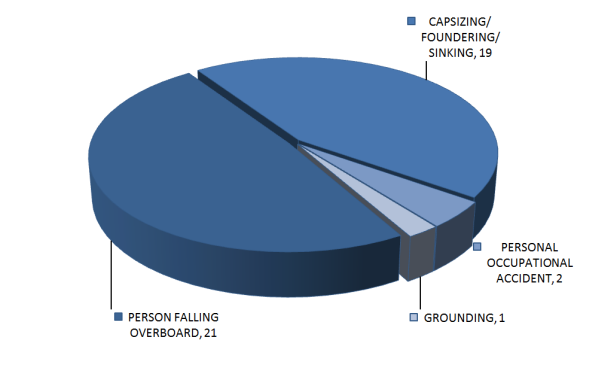

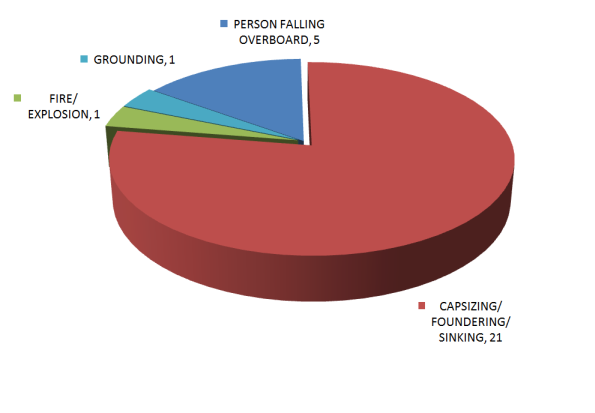

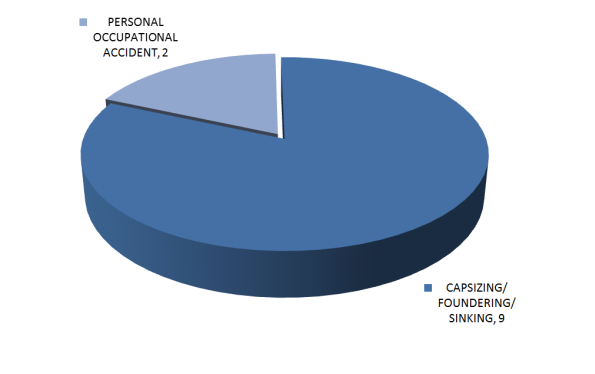

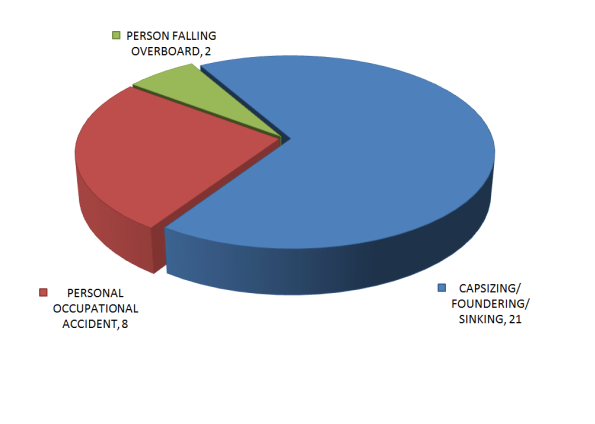

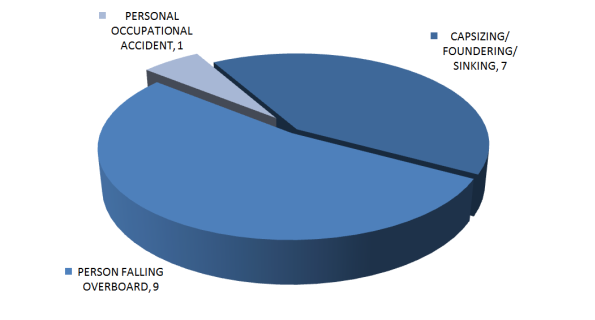

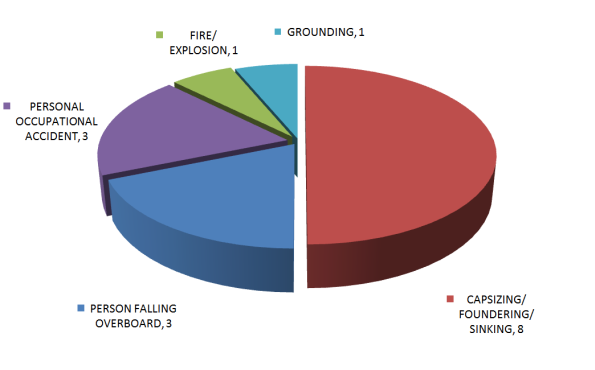

Of the 2514 fishing-related accidents examined, 112 were fatal, resulting in 154 deaths (Table 1). As shown in Figure 4 (the red cumulative percent line), the majority of deaths (89, or 58%) happened after a stability-related accident such as capsizing, foundering, flooding or sinking. There were 41 deaths (27%) due to falling overboard and 18 deaths (12%) from personal occupational accidents (accidents aboard ship).

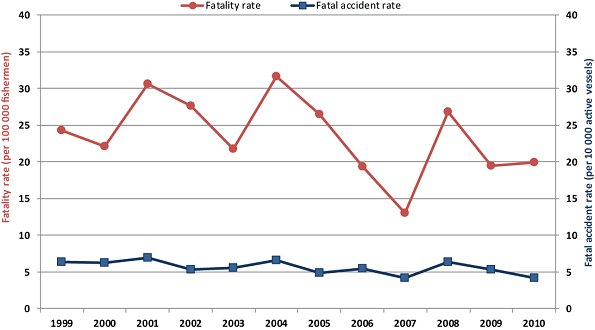

Although the fatal accident rate (the number of fatal accidents per 10 000 active vessels) showed a small but statistically significant downward trend from 1999 to 2010, as shown in Figure 5, the fatality rate (the number of deaths per 100 000 fishermen), though it varied from year to year, showed no trend. The average fatality rate for the period was 23.7/100 000 fishermen. An average of nearly 13 people died in fishing accidents each year.

Analysis of rates

Over the period examined, the number of active fishing vessels and the number of reported accidents declined. So did the overall accident rate and the fatal accident rate. Yet significantly, there was no corresponding decline in the fatality rate. This means that despite the fishing community's efforts to save lives, the likelihood of someone dying in a fishing accident in 2010 was not significantly lower than it was 12 years earlier, in 1999.

Figure 4 shows that 84% of all fishing-related fatalities recorded between 1999 and 2010 occurred when vessels capsized, foundered, or sank, or when persons fell overboard. This percentage is highlighted in yellow because the number of accidents in these categories is considerably less than that of many other categories such as grounding, which accounted for more than twice as many accidents as the other two categories combined, but only 2% of all fatalities. This information can assist the fishing community in deciding how best to direct its resources in order to improve safety.

Significant safety issues

As a result of this investigation, the Board identified 10 significant safety issues associated with fishing accidents. This section presents all 10 and analyzes each one using gap analysis. First, the report identifies the actual performance of the fishing community with respect to a particular issue by listing

- a particular issue by listing fishermen's practices that impact the safety issue; and

- policies and procedures of other members of the fishing community that impact the safety issue.

Then, the fishing community's actual performance is compared with its potential performance—that is, the overarching goal for each safety issue—and the gaps between the two are listed.

By identifying these gaps, as well as the safety action required to bridge them, the Board hopes to motivate members of the fishing community to work together to transform current fishing practices into safer behaviours and practices. The overall objective, in the Board's view, is a fishing industry that is equipped and ready to manage both the specific risks of each individual fishery and the common risks that apply to all.

Stability

GOAL - Fishermen understand the principles of stability and apply this understanding to make fishing operations safer.

Background

For many fishermen, experiencing a vessel's movements in a variety of operating conditions is the sole indication of whether a vessel is stable. However, this is not the same as measuring the vessel's ability to right itself, which can be done only by performing a stability assessment and documenting the results in a stability booklet.

The Small Fishing Vessel Inspection Regulations currently require, with certain exceptions,Footnote 21 a full stability assessment for vessels between 15 and 150 gross tons that do not exceed 24.4 m in length and are used in the herring or capelin fisheries. Once the proposed new Fishing Vessel Safety Regulations take effect, more vessels will be required to have a stability booklet.Footnote 22 However, stability information is based on complex mathematics and this is reflected in the way information is usually presented in stability booklets. Information that continues to be presented in this manner will be of limited practical value to fishermen.

As early as 1990, the Board recognized that the information in stability booklets was presented in a way that was not easily understood by fishermen. To that end, the Board recommended that TC establish guidelines so that the information “is presented in a simple, clear and practicable format for end-users.”Footnote 23 Work continues on the development of guidelines for the content and format for instructions to masters regarding stability assessments of their vessels as part of the proposed new Fishing Vessel Safety Regulations. The format will be based on the existing format developed by the International Maritime Organization and other research done in the United Kingdom. This work is scheduled to be completed by March 2013; therefore this recommendation has not been fully implemented.

Even without a formal stability assessment, stability can be improved if fishermen carry out safe work practices such as securing deck openings and maintaining freeboard. Stability can also be improved by recording vessel modifications and by considering the effects of adding, removing or rearranging gear and equipment to accommodate multiple fisheries. After the investigation of the Le Bout De Ligne accident in 1994, the Board recommended that TC emphasize the adverse effects of modifications and ensure they are recorded and accounted for when re-assessing vessel stability.Footnote 24 Even changes that seem minor may raise a vessel's centre of gravity and, together with other factors, increase the risk of capsizing.

In 2008, TC issued Ship Safety Bulletin 01/2008, which sets out a voluntary record of modifications for the benefit of owners/masters of any fishing vessels. For vessels of more than 15 gross tons, the record of modifications was to be reviewed by TC inspectors during regular inspections and entered on the vessel's inspection record. However, information gathered during the investigation showed minimal recording of vessel modifications.

Since 1990, the Board has identified stability as a major cause in several fishing vessel accidents. In one, which took place in 2002, five people died when the Cap Rouge II capsized off the mouth of the Fraser River in British Columbia. In another, in 2004, two people died when the Ryan's Commander capsized near Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland.Footnote 25

After the Cap Rouge II accident, the Board issued an overarching recommendation aimed at reducing unsafe practices by means of a code of best practices for small fishing vessels, including loading and stability. The intent was to encourage adoption of this code through education and awareness programs.Footnote 26 This recommendation has not yet been fully implemented. In the same investigation report, two more recommendations made to TC called for both new and existing inspected small fishing vessels to be required to have some approved stability assessment.Footnote 27 The Board then re-emphasized these recommendations during the investigation of the Ryan's Commander accident.Footnote 28

Many actions have been taken to improve stability awareness. The following are notable examples:

- In 2006, TC issued Ship Safety Bulletin 04/2006, which provides a standard interpretation of the discretionary power available under section 48 and the interim requirements prior to the implementation of the proposed Fishing Vessel Safety Regulations. The bulletin calls for vessels more than 15 gross tons to have a stability booklet where risk factors that negatively affect stability are present. However, these interim requirements have not been implemented consistently, except in Quebec, where TC inspectors have helped owners meet the requirements during vessel inspections.

- In 2007, with the coming into force of the Marine Personnel Regulations, competencies with regards to stability for Fishing Masters III and IV certificates of competency are required.

- National Research Council's Institute for Ocean Technology is currently contracted by and is working with TC and the fishing community to develop an assessment tool to identify populations of fishing vessels at low risk of stability-related accidents.

- Memorial University's Fisheries and Marine Institute (MI), along with the Canadian Council of Professional Fish Harvesters, is developing an electronic stability simulator to help fishermen learn about vessel stability.

- Fish Safe in British Columbia manages a stability education program developed and facilitated by fishermen.

Despite these actions, stability principles are still not widely understood or applied. As a result, fishing vessels may continue to operate without an assurance of meeting a minimum stability standard, putting lives at risk.

Practices and gap analysis

The following lists summarize the fishing community practices, policies and procedures that were identified and validated during the investigation as having an impact on the safety issues related to stability.

The Board found that fishermen

- generally do not understand or use information in stability booklets;

- sometimes build or modify vessels without assessing stability;

- determine the stability of a vessel based only on experiencing its movements in a variety of operating conditions;

- sometimes do not understand how watertight integrity impacts vessel stability;