Striking of berth

Roll-on/roll-off ferry Queen of Coquitlam

Departure Bay, Nanaimo, British Columbia

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

At approximately 1412 Pacific Standard Time on 18 November 2011, the Queen of Coquitlam was approaching berth No. 2 at Departure Bay, British Columbia. The vessel was operating with 1 of its 2 main engines, and the bow propeller was not engaged. The vessel deviated off course and struck the port-side fender located at the lead into the berth. There were no casualties or pollution; however, there was damage to the port bow of the ferry and to the fender's articulated pad.

Ce rapport est également disponible en français.

Factual information

Particulars of the vessel

| Name of vessel | Queen of Coquitlam |

|---|---|

| Official number | 370060 |

| Port of registry | Victoria, British Columbia |

| Flag | Canada |

| Type | Double-ended roll-on/roll-off ferry |

| Gross tonnage | 13 646 |

| Length Footnote 1 | 133 m |

| Draught | Forward: 5.34 m Aft: 5.4 m |

| Built | 1976 |

| Propulsion | 2 MaK diesel engines, with a total of 8848 brake horsepower (BHP), driving 2 controllable-pitch propellers (1 at each end of the vessel) |

| Passengers and vehicles | 607 passengers and 229 vehicles |

| Crew | 29 |

| Registered owner and manager | British Columbia Ferry Services Inc., British Columbia |

Description of the vessel

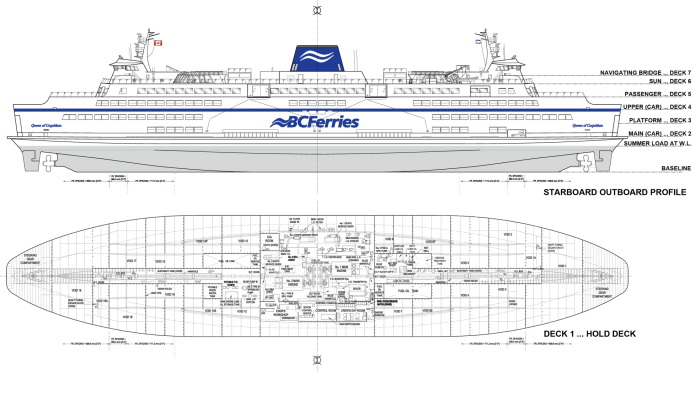

The Queen of Coquitlam is a double-ended vessel with a wheelhouse, controllable-pitch propeller and rudder at each end. The engine room is located amidships (Appendix C). The 2 ends are almost identical and, for the purpose of identification, are numbered No. 1 and No. 2. The location of the bow at either end establishes the port and starboard sides of the vessel and the numbering system of the machinery in the engine room. In this occurrence, the bridge watchkeepers were manning the No. 1 end.

The vessel is equipped with 1 anchor (along with the associated windlass, power unit, and controls), which is housed in a separate dedicated compartment located on the starboard forward part of the main car deck, at the No. 1 end.

Both the No. 1 and No. 2 wheelhouses have a manoeuvring station forward of the steering console, providing the operator with an unrestricted view forward. The telegraphs and the engine-speed levers are located there, as are pneumatic selector switches for changing between the 2 wheelhouses and the 2 modes of vessel operation.

The engine room contains 2 main engines, 3 auxiliary engines for electrical power generation, and their associated machinery and equipment. Two propeller shafts and intermediate shafts connect the main engines to the propellers via reduction gears.

An engine control room is located within the engine room. It contains the main electric switchboard and the means to remotely start, stop, and monitor the main engines and associated machinery. The inboard side of the engine control room is fitted with windows, and both main engines are partially visible.

The engine room manoeuvring station is located in the engine control room and contains the telegraphs and the engine-speed levers, along with pneumatic controls to engage and disengage the clutches, stop the main engines, and change control between the engine room/wheelhouse. Gauges for monitoring the main engines and ancillary equipment, as well as alarm panels, are also located there.

Modes of propulsion

There are 2 main engines, each with 2 pneumatic clutches. With this arrangement, there are 2 ways to operate the propellers, known as Mode 1 and Mode 2. In both modes, the 2 main engines are mechanically coupled and effectively behave as a single unit. In normal operation, both engines provide power. However, either Mode 1 or Mode 2 can be used with either 1 or both main engines.

Vessel speed is controlled by a pneumatic combinator connected to the speed-control lever; this arrangement automatically varies propeller pitch and engine revolutions per minute (rpm).

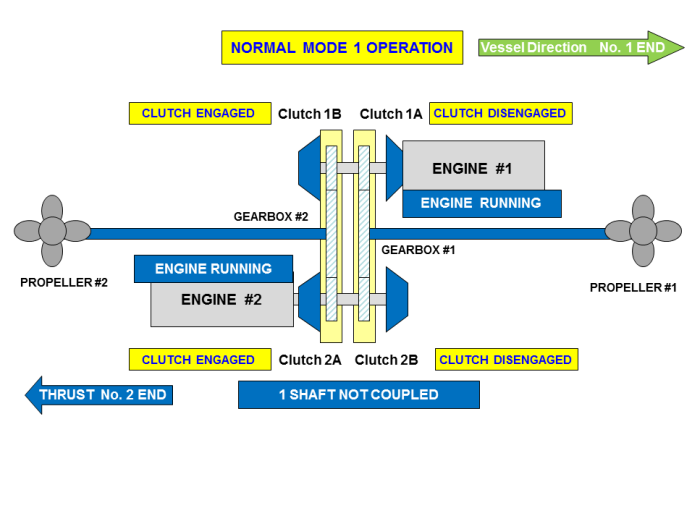

Mode 1

This mode is primarily used when the vessel has completed manoeuvring and is underway on passage. Footnote 2 In Mode 1, only the stern propeller is under power. Depending on the direction that the vessel is headed and how many engines are in use, the stern propeller can be engaged using a combination of clutches 1A and 2B or 1B and 2A (Figure 1). The forward propeller is feathered to reduce water resistance.

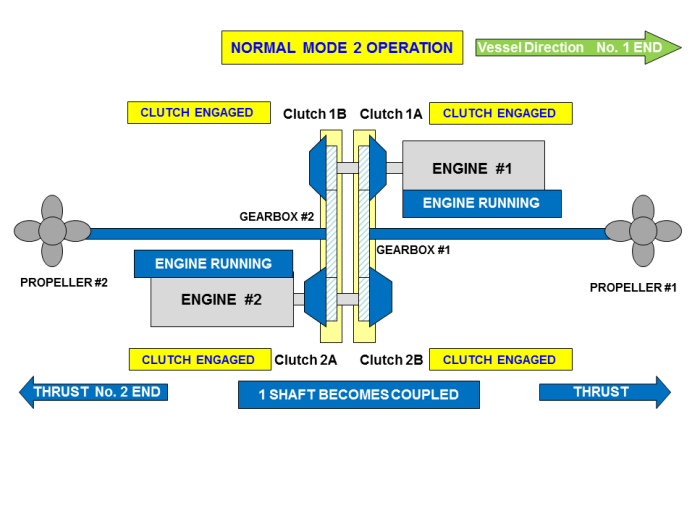

Mode 2

This mode is primarily used during docking and undocking. In this mode, if both engines are in use, all 4 clutches are engaged and provide power to both propellers (Figure 2). It takes approximately 90 seconds to engage Mode 2, as the bow propeller cycles from feathered to a pitch setting that allows the clutches to engage.

History of the voyage

At the time of the occurrence, the Queen of Coquitlam was based in Nanaimo, British Columbia, sailing between Departure Bay and Horseshoe Bay, British Columbia. Footnote 3 The crossing is 30 nautical miles (nm) long and takes approximately 95 minutes.

At 1235, Footnote 4 the vessel departed Horseshoe Bay terminal with 607 passengers, 229 vehicles and a crew of 29, heading to Departure Bay in Mode 2 propulsion. At 1238, the vessel switched to Mode 1 propulsion with both engines online. The second officer (2/O) was on watch, and the vessel was proceeding at 19.8 knots.

At 1331, fuel was observed leaking from the injector of cylinder unit B3 of the No. 1 main engine. This was reported to the chief engineer (C/E) in the control room. The bridge was asked to slow down the No. 1 main engine to assess if a reduction in speed would slow the fuel leak from the injector. The fuel leak continued. The engine room staff then tried to tighten the fuel line fittings to the injector. After the injector fittings had been tightened, the bridge was then asked to increase speed to see if tightening the fittings had been effective in stopping the leak. The injector continued to leak. The bridge was asked to stop the No. 1 main engine so that it could be taken offline and the injector could be replaced. The master was informed that the No. 1 main engine was being taken offline.

At 1341, the engine room staff members started the lockout procedure for the No. 1 main engine. They also locked out clutches 1A and 1B, thereby further isolating the engine from the reduction gear while the engineers worked on the No. 1 main engine, as per the vessel-specific manual (VSM) procedures. The C/E also decided to lock out clutch 2B, which provides the link between the No. 2 main engine and the forward propeller.

At 1400, the master entered the bridge and took over the watch from the 2/O. At this time, the vessel was proceeding at 16.8 knots and was abeam of Snake Island. At 1407, the 2/O started the pre-arrival checklist. As part of this procedure, the master tried to engage Mode 2 propulsion (engaging the bow propeller). At 1408, the engine room was asked to confirm the status of the No. 1 main engine and to see if it would be available for the docking. The engine room confirmed that the No. 1 main engine was shut down and would not be available for the duration of the trip. At 1409, as the vessel entered Departure Bay, the 2/O observed that Mode 2 had not engaged. The master called the engine room to check on the status of Mode 2 and was informed that Mode 2 was not available. The master prepared to dock using Mode 1 (only the stern propeller) with 1 engine. Footnote 5

At 1410, the master continued the turn to port in order to line up the approach to berth 2. The vessel was proceeding at 12 knots, approximately 5 cables from the berth. At 1411, the master applied astern propulsion in order to reduce the speed. At 1412, the vessel's bow veered off to port toward the outermost port-side fender. The master applied hard to starboard helm. Shortly thereafter, the master ordered the 2/O to sound the warning blast on the whistle and to make a public address announcement on the possibility of a hard landing.

At 1412:30 the vessel struck the port-side fender and articulated pad with the port side of the vessel's rubbing strake while proceeding at 4.3 knots. After the striking, the crew carried out an initial assessment to ensure that the vessel was safe to continue its berthing. When the initial assessment confirmed that it was safe, the vessel continued into its berth docking at 1414:40.

Certification

Vessel

The vessel was crewed, equipped and certified in accordance with existing regulations and, in addition, held a Safety Management Certificate as outlined in the International Management Code for the Safe Operation of Ships and for Pollution Prevention (ISM Code).

Personnel

The master, officers and crew held certificates of competency appropriate for the intended voyage and the type of vessel on which they were working.

Environmental conditions

The local Environment Canada weather station in Nanaimo indicated winds of 15 km/h from north-northwest at 1400 hours. Local weather was reported to be mostly cloudy with a temperature of 3.2ºC.

High tide in Nanaimo was 4.4 m at 1136, and low tide was 2.7 m at 1813. The height of the tide for Nanaimo Harbour at 1400 was calculated at 3.8 m above chart datum.

Damage to the vessel

The damage to the vessel was confined to the No. 1 end port bow rubbing strake (Photo 2). The damage between frames 90 and 96 was approximately 7.0 m in length and up to 1.0 m in depth. This resulted in a breach of the hull into the No. 1 end rudder compartment. The plating of the superstructure adjacent to this area was also buckled.

There was a large indentation in the rubbing strake to port of the centreline of the vessel, where the initial contact occurred. This indentation had a width of approximately 0.6 m and a maximum depth of 0.1 m (Photo 3).

Damage to the berth

Damage to berth 2 (Appendix B) was limited to the port-side leads. This included damage to the outermost port-side fender and its articulated pad. As a result of the collision, the complete articulated landing pad broke free from the fender and ended up on the ocean floor. The attachment points between the fender and the articulated landing pad were torn away (Photo 4).

The design of the fender and the articulated landing pad allows for a cushion effect during normal landings (Photo 5).

Berthing procedure

The Queen of Coquitlam VSM (Shipboard Operation - Deck, 7.1.16, Control System) describes the use of the “T”

and “L”

control handles. The “T”

handle controls the pitch and rpm of the stern propeller, and the “L”

handle controls the same for the bow propeller.

Prior to arrival, the master rings “standby”

and slows the vessel down using the “T”

handle in Mode 1. At the location indicated in the VSM, the master switches over to Mode 2. The forward propeller now has power, and the master uses the “L”

handle to vary rpm and pitch, slowing the vessel's forward progress. This is achieved using the forward propeller, which applies thrust in the opposite direction to the stern propeller. During this manoeuvre, the forward and stern propellers are both turning in their respective “ahead”

direction.

During berthing, the stern and forward rudders are controlled by their respective jog steering controls. The force of the wash created by both propellers acts upon their respective rudders; this causes the vessel's bow or stern to swing in the required direction, allowing greater control over the movement of each end of the vessel. This is very important for safe manoeuvring, particularly in rough weather conditions. Once in the berth, the propulsion system remains in Mode 2, and the forward propeller is set to a slight astern pitch, while the stern propeller is set to a slight forward pitch.

Controllable-pitch propellers

The controllable-pitch (CP) propeller differs from the conventional propeller in that its blades rotate around its axis and change pitch variably between headway and reversing. In the case of the Queen of Coquitlam, when viewed from the respective stern, the propeller blades rotate in a right-hand or clockwise direction on the No. 1 end of the vessel, and in a left-hand or counter-clockwise direction on the No. 2 end.

Transverse thrust

Transverse thrust is the tendency for a forward or astern running propeller to move the stern to starboard or port, and is caused by an interaction between the hull, propeller and rudder. On a vessel with a left-hand turning CP propeller with astern pitch, transverse thrust results in a tendency for the bow to swing to starboard and the stern to port. Transverse thrust is more pronounced when the propellers have astern pitch.

Bank cushion effect

Bank cushion is the effect on a vessel approaching a steep underwater bank, in this case, at an oblique angle. As the vessel moves forward, displaced water produces a cushion effect at the bow before filling the void behind the stern. In turn, the push-back from this build-up of water exerts pressure on the bow, causing the vessel to sheer away from the bank. The magnitude of the bank cushion effect is influenced by several factors, including vessel distance from the bank, vessel speed, under keel clearance and channel profile. Footnote 6 Given that the Queen of Coquitlam entered the berth with a rising shore on the starboard side, the bank cushion effect would have been to port.

Communications

During the ongoing attempts to rectify the problems affecting the No. 1 main engine, the bridge and engine room personnel communicated on several occasions while trying to isolate the cause. In addition, the C/E and master discussed the required repairs to the injector. The C/E informed the master that in order to conduct the necessary repairs, the No. 1 main engine would be offline for the remainder of the voyage to Nanaimo. The clutch configuration and availability of Mode 2 were not discussed during these conversations.

As the vessel entered Departure Bay, the bridge crew called the engine room to check on the status of the No. 1 main engine. The C/E informed the bridge crew that the No. 1 main engine was not available for this docking. When Mode 2 would not engage, the master called the engine room to inquire as to why it was not engaging, and was informed by the C/E that it was not available.

Shipboard operating procedures

The Queen of Coquitlam VSM contains standard operating procedures for all aspects of the vessel's operation, including pre-arrival procedures and checklist, engine room control systems information, main engine shut-down procedures and single-engine operation procedures.

Deck procedures

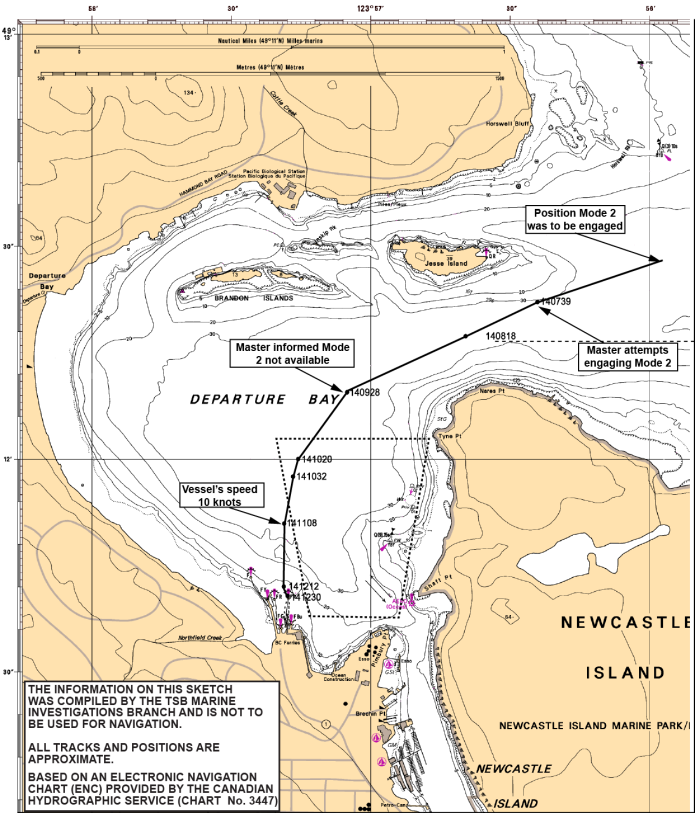

The Queen of Coquitlam VSM (Shipboard Operation – Deck, 1.1.12) states that when proceeding westward toward Departure Bay, Mode 2 should be activated when abeam of Horswell Buoy, which is at a distance of 1.5 nm from the berth.

Engine room procedures

The Queen of Coquitlam VSM (Emergency Procedures – Critical Systems, 8.2.4) states that when a main engine is to be shut down while operating in Mode 1, there are 7 steps that must be carried out.

Step 5 of that procedure states that the engine room should isolate the appropriate clutches, but does not specify which of the 4 clutches should be isolated. Step 7 states that the bridge must be notified as to the status of the machinery.

Analysis

Events leading to the striking

As the Queen of Coquitlam approaches Departure Bay, the procedures in the VSM require that the vessel switch from Mode 1 to Mode 2 for arrival and docking. The procedure detailing pre-arrival checks Footnote 7 specifies that Mode 2 is to be engaged when abeam of the Horswell Buoy. The master did not attempt to engage Mode 2 until abeam of Jesse Island, which is 0.5 nm west of the Horswell Buoy and closer to the berth. Furthermore, the bridge crew did not notice that Mode 2 had not engaged until the vessel was inside Departure Bay, 0.9 nm west of Horswell Buoy. By not attempting to engage Mode 2 at the location specified in the VSM, the master had a reduced amount of time to assess the situation and take corrective action.

Following the master's attempt to engage Mode 2, the 2/O noticed that Mode 2 had not engaged. Footnote 8 The master called the engine room to find out why Mode 2 had not engaged. The C/E informed the master that Mode 2 was not available. If Mode 2 had been engaged at this point, it would have taken approximately 90 seconds for the propeller to feather to the right position and then for the clutch to be engaged. Without questioning the C/E as to why Mode 2 was not available, the master decided to berth the vessel using Mode 1. He had previously performed this type of docking. The vessel had less power to reduce speed and only the stern propeller to manoeuvre with.

When the vessel was 0.25 nm from the berth, its speed was 10 knots. At 1411:18, when the vessel was only 0.2 nm from the berth and proceeding at 8 knots, the master applied reverse pitch to reduce speed. Due to the bank cushion effect and the vessel's speed, the bow moved rapidly to port, resulting in the vessel striking the fender.

Lockout procedures for clutches

When a problem occurred with 1 of the injectors of the No. 1 main engine, the engine room staff attempted to resolve the problem. Initial attempts were not successful, and the C/E decided to take the No. 1 main engine offline to conduct repairs. Using the company's VSM checklist, the C/E made preparations in the engine room to change out the leaking injector. Part of this process included locking out the clutches linking the No. 1 main engine to both shafts (clutches 1A and 1B). During this procedure, clutch 2B was also locked out, which prevented Mode 2 from being available to the bridge as the vessel approached the berth.

The Queen of Coquitlam VSM sets out a 7-step procedure to address the shutting down of a main engine while the vessel is operating in Mode 1. Step 5 states that the engine room is to lock out the appropriate clutches. It does not specify which of the 4 clutches need to be locked out when an engine is shut down.

Because the VSM did not clearly specify which clutches to isolate in various operational conditions, the manoeuvrability of the vessel was reduced when clutch 2B was isolated. Therefore, in the absence of specific information regarding the operation of a vessel's critical equipment, the engineering staff may unnecessarily lock out clutches that are available for the manoeuvrability of the vessel.

On-board communications

Following the discovery of the leaking injector on the No. 1 main engine, numerous conversations took place between the engine room and the bridge. During these initial conversations, an attempt was made to isolate the root cause of the leaking injector. Once it was determined that the leaking injector had to be replaced, the engine room informed the bridge that the No. 1 main engine was being taken offline.

The Queen of Coquitlam VSM includes a 7-step procedure to address the operation of the vessel using only Mode 1. Step 7 states that the bridge must be notified as to the final status of the machinery. The C/E was aware that, with the final clutch arrangement (with clutch 2B being locked out), Mode 2 was not available for the docking procedure, but did not pass that information on to the master. Given that Mode 2 can be used with only 1 operational engine, the master expected that Mode 2 would still be available for the docking.

The communications between the engine room and bridge addressed the status of the main engine, but did not include information as to which clutches were locked out or the fact that Mode 2 was not available.

As the vessel entered Departure Bay, it became apparent to the bridge crew that Mode 2 had not engaged. Upon calling down to the engine room to find out why it was not engaging, the master was told by the C/E that it was not available.

Incomplete communications between the master and the C/E led to a lack of understanding regarding the status of Mode 2 and its availability for docking, thereby compromising the safe docking of the vessel.

Movement of vessel to port

During the approach to berth 2 at Departure Bay, the vessel approached the shoreline close to starboard at an oblique angle. This shoreline has a steep underwater bank. The approaching vessel forced water into the narrowing gap between the vessel's starboard bow and the shore. The water being pushed ahead of the bow created a pressure on the landward side. The pressure created by the water acted on the starboard bow, causing the vessel to sheer away to port, away from the bank.

The master applied starboard helm and briefly applied forward pitch to create a wash over the rudder, to then counteract the vessel's movement to port. When the master then re-applied reverse pitch on the CP propeller to reduce the vessel's speed, the result was a reduction in water passing over the No. 2 end propeller and a reduction in steerage way. The bank cushion effect caused the vessel to move to port toward the port-side fender.

The master was not able to counteract these forces, which were compounded by the vessel's speed as it approached the berth. Consequently, the Queen of Coquitlam struck the port-side fender. Under normal circumstances, with both engines and propellers operational, the master would have had sufficient control to compensate for these forces.

Findings

Findings as to causes and contributing factors

- The bow propeller was unavailable because the clutch to engage the bow propeller was locked out in the engine room.

- By not attempting to engage Mode 2 at the distance from the berth specified in the vessel-specific manual, the master had a reduced amount of time to assess the situation and take corrective action.

- Incomplete communications between the master and the chief engineer led to a misunderstanding as to the status of Mode 2 and its availability for docking, thereby compromising the safe docking of the vessel.

- The master was not able to counteract the bank cushion effect which was compounded by the vessel's speed as it approached the berth. As a result, the vessel struck the port-side fender.

Safety action

Action taken

On 11 April 2012, the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) issued Marine Safety Information Letter (MSI) 04/12 to advise British Columbia Ferry Services (BCFS) of the safety issues identified in the investigations into the berth strikings of both the Coastal Inspiration Footnote 9 and the Queen of Coquitlam. A copy of the letter was also sent to Transport Canada. The letter briefly outlined the events of the occurrences and identified the unavailability of Mode 2 and the speed of advance into the berth as significant safety issues. The letter also acknowledged that BCFS had been proactively attempting to rectify these safety issues by reviewing all passage plans using a risk-based approach.

On 23 May 2012, the BCFS responded to MSI 04/12 by stating that it had implemented new standard operating procedures for speed reduction. For example, as the vessel proceeds, it must now pass through pre-determined “gates”

that will be standardized for each route and will provide safety checks as the vessel approaches the conclusion of the voyage. To further mitigate the risks involved in the vessel berthing phase, BCFS has also developed a series of contingency plans and drills. While BCFS did not provide details about the contingency plans, it does explain that the drills include regularly rehearsing several key responses designed to slow or stop the vessel in the event of a propulsion failure that hampers the ability to reduce speed while approaching the berth.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board's investigation into this occurrence. Consequently, the Board authorized the release of this report on . It was officially released on .